The impact of the pandemic on international housing markets: is there a risk of overheating?

Despite COVID-19, house prices in most advanced economies rebounded in 2020, largely thanks to the expansionary fiscal and monetary policies introduced to revive economic activity.

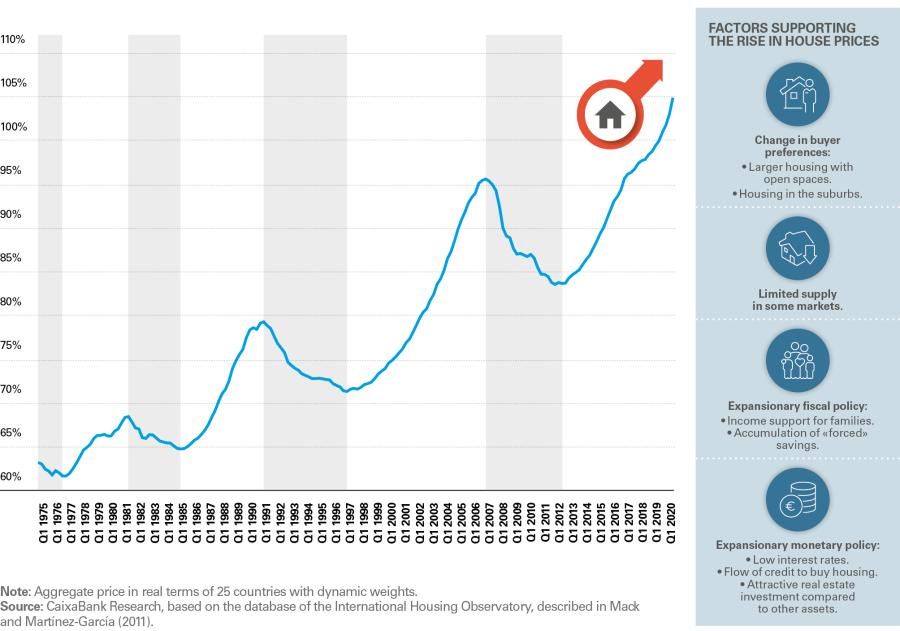

Global house prices accelerate their upward trend during the pandemic

Despite COVID-19, house prices in most advanced economies rebounded in 2020, largely thanks to the expansionary fiscal and monetary policies introduced to revive economic activity. Some real estate markets were already close to being overvalued before the pandemic, so the faster growth in prices has merely fuelled debate about the risks of overheating in certain countries. Such risks could possibly be managed with so-called macroprudential tools but could also raise questions regarding the need to adjust some monetary policy tools before the economic recovery is fully established.

The initial assumption of many analysts at the outbreak of the pandemic last year was that residential property markets would be severely affected by the fall in household income due to the economic downturn. As it turns out, nothing could be further from the truth: real house price growth at a global level accelerated during the pandemic. According to the indicator produced by the Dallas Fed’s International Housing Observatory,24 global house prices picked up from 1.8% growth in 2019 to 3.6% in 2020 in real terms (from 3.2% to 4.6% in nominal terms).

- 24See: https://int.housing-observatory.com/

Global house prices gather speed during the pandemic

Index (100 = Q4 2019)

Why have house prices increased during the pandemic? The role of monetary policy

The upward trend in house prices during the pandemic reflects several factors linked to the surge in demand driven by the particular features of the crisis. People being confined to their homes and the increase in teleworking have brought about a change in buyers’ preferences regarding the type and location of their home. In addition, fiscal policies have cushioned the impact of the crisis on household income, albeit to a greater or lesser extent depending on the country. In fact, in many advanced economies households have accumulated large amounts of «forced» savings due to strict lockdowns and restrictions on certain activities, and some of these savings have been channelled into real estate investment. On the supply side, the decline in construction in the second half of 2020 affected the number of properties delivered, helping to push up prices, especially in markets where housing was already in short supply.

In addition to the recovery in demand and the restrictions

that temporarily limited supply, low interest rates are also pushing up house prices.

An additional factor that has had a decisive impact on rising house prices has been the low interest rates (and the expectation that they will remain low for a long time) as a result of the monetary policy adopted to stimulate the economy. Numerous academic studies have shown that house prices tend to rise when mortgage interest rates fall, as buyers can afford a more expensive home for the same mortgage payments, and real estate investment becomes more attractive in an environment of low returns on alternative assets considered as safe. The pandemic may have reinforced this relationship between interest rates and house prices: the forced savings accumulated by households, together with very low interest rates, have meant the option of investing these savings in real estate has gained even more weight.25

- 25In terms of size, a recent study by the International Monetary Fund suggests that a 100 basis point change in interest rates would have an impact of between 1.5 and 2 basis points on the rate of change in house prices. See the presentation: «The Global Real Estate Boom: Is It Time to Worry Again? available at https://ieo.imf.org/-/media/IEO/Files/Seminars/ieo-webinar-igan-real-estate-markets-covid19-june-2021-v2.ashx

The impact of COVID-19 on prices has been uneven across countries

The acceleration in the growth of the global house price index is widespread in advanced economies (with the notable exception of Japan) but the rate of increase varies widely across countries, as the following tables show. If we look at the change in the annual rates in 2019 and 2020, we can differentiate between two groups: countries with faster house price growth in 2020 and countries with slower growth.

Canada (+8.3 pp up to 8.2% in 2020) and Luxembourg (+4.4 pp up to 14.5%) stand out in the first group, followed at some distance by Denmark, the United Kingdom, France and Italy, where annual price growth increased by at least 2 pp.

Countries where house prices accelerated in 2020

Countries where house prices slowed down in 2020

In this group of countries, it can be seen that the pandemic has, in many cases, led to a change in trend compared to previous years. This is the case of Canada (+8.2% in 2020 after two consecutive years of falling prices), Denmark (+4.8% in 2020 after years of slight price moderation), the UK (+2.0% compared to the downward trend since the historical rates of 2015) and the US (3.8%, breaking the trend of moderation from the previous five years). However, as the change in trend appears to be a response to the effects of the pandemic, we do not expect any significant or worrying overheating in the residential market; in fact, this should moderate or correct itself as these effects (such as changing habits, tax relief or supply shortages) dissipate.

Signs of overheating in most real estate markets predate the pandemic,

although the «temperature» increased significantly in 2020.

In other countries, prices were already growing at fast rates before the pandemic and accelerated further in 2020. A case in point is the Luxembourg residential market, whose prices did not overheat during the 2000-2007 expansionary cycle but grew steeply and more or less gradually (10.1% in 2019), accelerating even further over the past year (14.5% in 2020) to values equivalent to an overheated market (to which we must also add an increase in household debt, up to 175% of disposable income in 2020).

In the second group of countries (those recording a moderation in house prices between 2019 and 2020), Hungary (with a sharp decline of –12.6 pp down to +4.4% in 2020) and Latvia (–5.3 pp down to +3.7%) stand out, followed at a greater distance by Spain, Slovenia and Ireland, among others, all of which recorded a fall in the annual growth rate of at least 2 pp. In contrast to the previous group of countries, in this case all countries recorded a decline in line with a trend already occurring before the outbreak of the pandemic. Broadly speaking, these are residential markets that had become more or less overheated in the economic cycle ending with the global financial crisis of 2008. In other words, economies which, between 2000 and 2007, saw fast growth in prices, a sharp increase in residential investment’s share of GDP and high household debt. These countries have since corrected such excesses and are now in a relatively expansionary phase of the cycle.

Should we be concerned about rising prices? Are there signs of overheating?

In general, the statistical models used to estimate whether or not house prices are overvalued are subject to a high degree of uncertainty and should be interpreted with caution. As we will see below, various indicators suggest that, in general, there are signs of overvaluation in some markets but not across the board. Moreover, in these cases the situation was not caused by the outbreak of the pandemic but a trend that had already been observed.

The ECB produces a very useful indicator to assess whether prices are moving away from equilibrium levels.26 According to this indicator, the Luxembourg market was already showing clear signs of overvaluation before the pandemic and recovered in 2020, an interpretation that is consistent with the analysis earlier in this article. Then, at a greater distance, we can find countries such as Austria, Germany and Belgium, which showed certain signs of being overvalued before the pandemic and increased in 2020. In fact, the ECB notes that house price growth during the pandemic has generally been higher in those countries that were more overvalued before the advent of COVID-19.

- 26The ECB indicator is a simple average between the ratio of house prices to household income and the result of a model designed to detect house price misalignments from fundamentals. Specifically, this model statistically relates the trend in house price-to-income, the real mortgage interest rate and the housing supply per capita. The methodology is described in Box 3 of the Financial Stability Review, ECB, May 2015.

The risks of overheating are more limited in countries where price rises have accelerated due to pandemic-related factors,

while the risks have increased in countries that were already showing signs of overheating before the appearance of COVID.

Another indicator to assess whether house prices are moving away from equilibrium levels is the Exuberance Indicator, created by the Dallas Fed for a group of developed economies.27 The markets where house prices are most overvalued would again be Luxembourg, closely followed by Germany (overvalued since 2016) and Japan (even though house prices are falling). The Netherlands would be the only economy where signs of overvaluation emerged during the pandemic.

- 27The Exuberance Indicator detects explosive periods in the house price-to-income ratio. For more details on its construction and calculation, see the work of Mack, Adrienne and Enrique Martínez-García (2011), «A Cross-Country Quarterly Database of Real House Prices: A Methodological Note».

Countries with clear signs of overvaluation in the residential market

Relative share of all the countries studied

A recent study by the Bank for International Settlements28 concludes that, since the start of the pandemic, house prices have risen more than would be implied by developments in fundamentals, such as the cost of mortgage loans and household income. In particular, based on the historical relationship of house prices to household income and interest rates, house prices in many countries would be expected to rise from the beginning of 2020 but, in most cases, by less than the actual increase observed. This apparent misalignment between house prices and their fundamentals could lead to corrections in the future.

- 28See «House prices soar during the COVID-19 pandemic», published in the BIS Annual Economic Report, June 2021.

Is it different this time around?

A catalyst for the housing boom that led to the global financial crisis of 2008 was the rapid growth in household credit to purchase a home, creating a kind of vicious circle in which higher house prices boosted growth in credit. Everything seems to indicate that the situation is different this time, for the following reasons:

- The growth in loans to households with a low credit rating has been contained in recent years, thanks largely to much tighter lending standards among the large developed economies. For example, in the US the proportion of loans granted to people with a low credit rating is relatively small.29

- There is no clear association between the recovery in house prices and credit growth but rather the opposite: prices have risen most in those countries where households have deleveraged the most during the five years before the pandemic. This situation contrasts with what happened during the five years preceding the global financial crisis, as can be seen in the following charts.30 Spain perfectly illustrates this paradigm shift: between 2001 and 2006, credit to households increased from 47% of GDP to 78% (+31 pp) and house prices rose by 71%. By contrast, between 2014 and 2019 credit to households fell from 73% of GDP to 57% (–17 pp) while house prices rose by a moderate 8%.

- There is a third reason why the situation might be different this time around: the household debt burden in most developed economies is smaller than in the last international financial crisis. Therefore, in the event of a rise in interest rates, households would be less vulnerable than in other recessions, when the residential market was at the epicentre of the crisis.

- 29In 2007, 1 in 4 new mortgage loans was granted to a buyer with a low credit rating (below 659). In contrast, this share was only 5% in 2020, while 70% had a high rating (above 760), similar percentages to previous years.

- 30In both charts, Ireland appears as an outlier. If we exclude this country, the correlations would be 0.73 in the period 2001-2006 and –0.09 in the period 2014-2019.

Relationship between the increase in credit to households and house prices

The debate concerning the residential market has reached the central banks

The current situation of some developed residential markets has not gone unnoticed by central bank governing councils. Once again, questions have been raised concerning the role played by extremely accommodative monetary policy in pushing up financial asset prices. Our analysis suggests that some housing markets were already close to being overvalued before the pandemic and, indeed, some central banks are beginning to warn of the additional imbalance in house prices caused by fiscal and monetary stimuli. Such risks could possibly be managed using macroprudential instruments but might also result in the need to adjust some monetary policy tools before the economic recovery is fully established.31

- 31There is also growing concern about the impact of monetary policy on inequality, since rising house prices would make it even more difficult for young people and low-income workers to buy their own home. In addition, a certain «crowding out effect» would be created, as higher-income households would be moving to the outskirts of large cities, where lower-income families have traditionally lived.

Aware of the impact of monetary policy on house prices,

central banks are keeping a close eye on property market developments.

In the euro area, this debate has taken its toll on the ECB’s new strategy, encouraging the European statistics agency, Eurostat, to look at how house prices could be better incorporated into the HICP, as currently only rental prices are included. For now, the ECB will limit itself to monitoring house prices as another aspect in its discussion of price developments (as it does with wage trends). For their part, several Fed members have expressed concern about recent developments in US house prices. The minutes from the 15-16 June meeting mention concerns about the financial risk associated with strong housing demand and also, in the discussion on reducing the purchase programme, a call to lower MBS purchases (Mortgage Backed Securities).32 In other regions, central banks have already taken action and introduced macroprudential measures. For example, the Central Bank of New Zealand has reimposed loan-to-value restrictions on new mortgages to reduce the risks associated with an overheated residential market.

- 32For a more in-depth review of the minutes from the meeting on 15-16 June, visit the following link: https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcminutes20210616.pdf

An overview of the US residential market: no worrying signs of overheating for the time being

The US residential market became overblown in the previous economic cycle, ending with the bursting of the real estate bubble and the global financial crisis in 2008. As from 2013 there were more evident signs of the market recovering and, just before the arrival of the economic and health crisis generated by COVID-19, prices were posting very modest growth rates (+2.0% annually in 2019), house sales were growing in line with demographic trends (similar to their long-term average between the 1980s and 1990s) and residential investment accounted for just under 4% of GDP.

The outbreak of the pandemic was a stimulus for the US residential sector right from the start: sales of new single-family homes soared (+45% year-on-year in Q3 2020), house prices have been growing at double-digit year-on-year rates since December (+14% in April 2021) and residential investment accounted for 4.8% of GDP in Q1 2021. Although travel restrictions were somewhat more moderate than in Europe, much of this upturn is also due to changing habits and a preference for living in larger spaces and away from urban centres.33 However, another influence has been the investment of pent-up savings during the pandemic, particularly after the strong fiscal policy of direct stimuli for the population implemented by both the Trump and, more recently, the Biden Administrations, as well as the Federal Reserve’s monetary stimulus package. Finally, there are also problems on the supply side; some of a more temporary nature such as difficulties in finding skilled labour and the rising cost of some materials, and other factors that were present before the pandemic, such as the shortage of attractive land.

In short, the US case is striking because the pandemic has pushed up indicators for housing market activity to rates similar to those seen during the sector’s boom in 2000-2006. However, it is still too early to be overly concerned about this development, which could be a one-off or short-term boost as a direct reaction to the effects of the pandemic and the considerable package of stimuli. In fact, the house price-to-income ratio fell slightly in 2020 due to higher growth in income than in prices and it is still well below the levels reached in the previous boom. Other indicators (such as sales of new builds) are already showing signs of moderating towards pre-pandemic trends.34

- 33See Gupta et al. (April 2021), «Flattening the curve: pandemic-induced revaluation of urban real estate», NBER Working Paper 28675.

- 34For a more complete analysis of the US residential market, see «The US housing market does not appear to be a bubble», published by Credit Strategy Research, Goldman Sachs, July 2021.