A shift in the EU’s political priorities

The new European Commission has completed its first 100 days amid turmoil in transatlantic relations. The implementation of Trump’s agenda (and the accompanying drama) is accelerating the change in political priorities that was already foreseen for von der Leyen’s second term. The urgent need to build a more competitive EU now seems indivisible from the goal of maintaining the security and integrity of its borders. The next 2028-2034 budget cycle should reflect the bloc’s ambition in relation to these medium-term challenges, but between now and when that budget will be defined, there are tough negotiations to be had on how to finance it and critical questions to be answered on matters such as the future of Ukraine and climate commitments.

A plan to find direction in global competitiveness

On 29 January, the European Commission presented the Competitiveness Compass.1 This is a roadmap for 2025-2026 that translates the recommendations of the Letta and Draghi reports2 into policy actions focusing on the three key objectives of the latter report: to close the innovation gap vis-à-vis global competitors, to pursue competitive decarbonisation and to reduce strategic dependencies. In addition to the specific actions proposed for each of these objectives, the roadmap includes five general priorities, which include simplifying business regulation, making further progress in the integration of the Single Market, boosting financing with new savings and investment products, ensuring the provision of appropriate skills in the labour market and improving the coordination of European instruments with a boost to common projects.

The European Commission has already put forward several proposals for political action in relevant areas, and these must now be endorsed by the Council and the European Parliament. The proposals include two packages of measures aimed at simplifying regulation in the sphere of sustainability, with a view to easing the administrative burden on companies by at least 25% (35% in the case of SMEs). Another of the proposals is a new clean industry pact, which includes the deployment of 100 billion euros for the production of clean technologies in the EU and an action plan to cut energy costs for consumers and businesses, which could entail savings of 45 billion in 2025 (and up to 260 billion in 2040).

As for what is yet to come in 2025, there are high expectations for the revision of regulations covering state aid and the competition framework, as well as the strategy for reducing the fragmentation of the internal market. On this latter note, a proposal has already been put forward to establish a Savings and Investments Union (SIU),3 the main objective of which is to facilitate the channelling of household savings into financing for strategic sectors.

- 1See European Commission (2025). «A Competitiveness Compass for the EU», communication from the European Commission, COM(2025) 30 final.

- 2See the Focus «Draghi proposes a European industrial policy as a driving force to address the challenges of the coming decades» in

the MR10/2024. - 3European Commission (2025). «Savings and Investments Union: A Strategy to Foster Citizens’ Wealth and Economic Competitiveness in the EU», communication from the European Commission, COM(2025) 124 final.

Defence spending, more and faster than expected

In 2025, between the Competitiveness Compass and new geopolitical realities, the EU is hastening to reduce its strategic dependence on the US in defence matters.4 The catalyst for this urgency has been the new Trump administration’s unilateral approach to foreign policy, which has fractured the transatlantic axis with harsh rhetoric against Europe – far from the expected transactional approach – and has given Russia leeway beyond the Ukraine conflict.5 The response has come in the form of an ambitious package of measures (ReArm Europe), which is expected to include the activation of the escape clause in the fiscal rules, enabling the release of some 650 billion for defence spending over the next four years, as well as a new EU instrument with 150 billion in loans to Member States to facilitate joint purchases and to bolster pan-European capabilities (Security Action for Europe, SAFE).

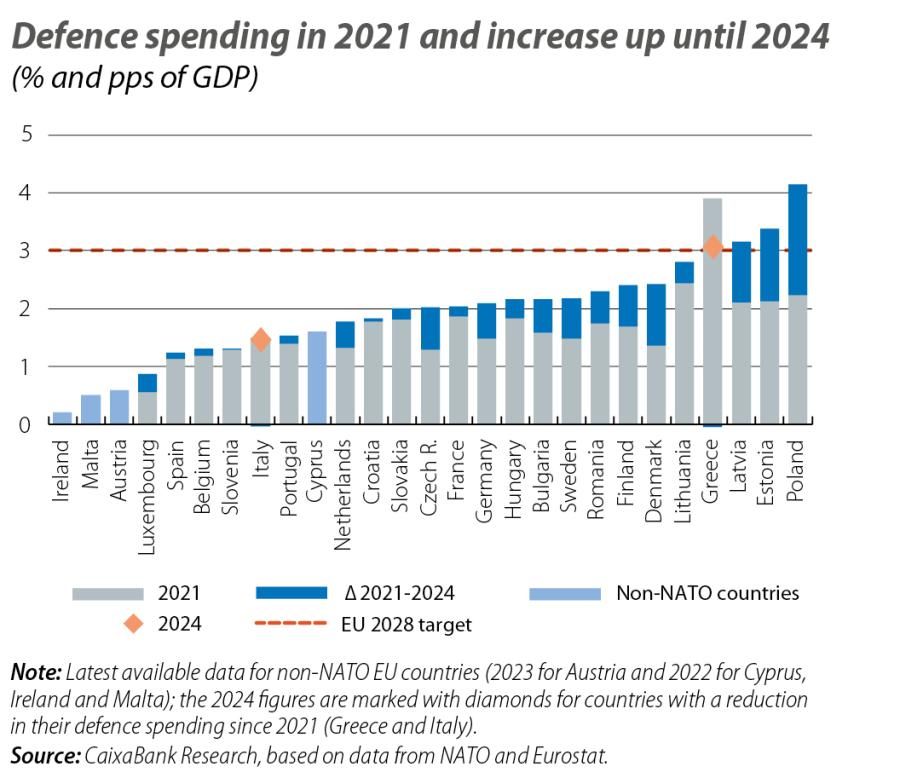

This package of measures would allow annual defence spending for the EU as a whole to increase by just over 1 point of GDP by 2028, bringing it above 3% and approaching the US’ levels of the last decade. However, the starting point varies widely, so if a common objective is set then the fiscal effort would also vary widely between Member States (see first chart). For obvious reasons, the countries bordering Russia and Ukraine have registered the sharpest increase in defence spending since 2021 and have shown the highest ratios in 2024, with Poland standing out at 4.2%. Among the bloc’s large economies, Germany and France were around the average, followed some way behind by Italy (1.5%) and Spain (1.2%). In some cases, filling this gap will put additional stress on their limited fiscal space,6 so it is likely that they will redirect unused EU funds, such as those from the NGEU programme.7

- 4European Commission (2025). «Joint White Paper for European Defence Readiness 2030», JOIN(2025) 120 final.

- 5See the Focus «Ukraine’s reconstruction and its potential energy

implications for Europe» in this same Monthly Report. - 6See the Focus «The new EU economic governance framework» in

the MR01/2025. - 7See the Dossier «The transformative capacity of NGEU and other fiscal stimulus plans» in the MR03/2025.

Prioritising with a budget that is up to the challenges ahead

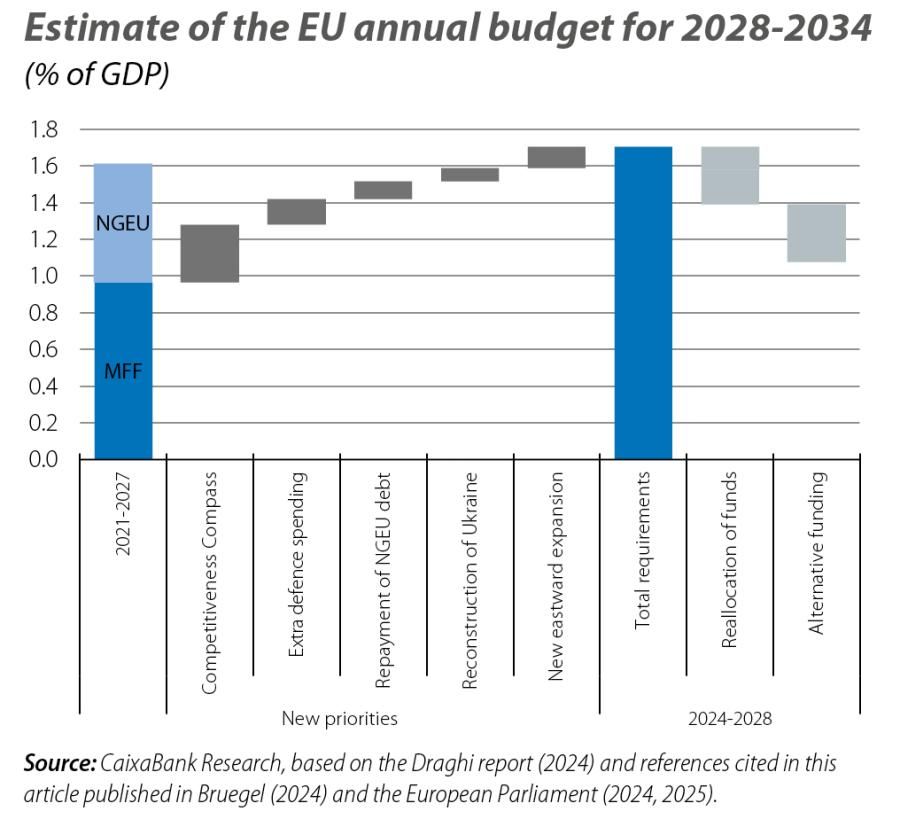

The European Commission will present its proposal for the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) 2028-2034 in July this year. This new budget cycle begins in a very different context from the previous one, which was approved in 2020 at the height of the pandemic. The geopolitical environment seems more hostile, with an armed conflict on the EU’s eastern border and a breakdown of the historical transatlantic alliance, including the geo-economic alliance, with risks of escalating protectionism and trade fragmentation. Addressing this scenario will require considerable resources in order to simultaneously fund the Competitiveness Compass, higher defence spending, the reconstruction of Ukraine8 and a possible new phase of eastward expansion led by this country, as well as the repayment of the pooled debt issued to finance the NGEU programme.10 Taking all these factors into consideration, we estimate that the EU’s annual budget could increase from 1% of GDP in 2021-2027 to total expenditure requirements of 1.7% in 2028-2034, a similar jump to that entailed by the NGEU funds (see second chart).11 A portion of this increase could be channelled through a reorientation of resources from the previous cycle, including those not used from NGEU, as well as other alternative sources of funding: issues of pooled debt, new internal EU funds or even the use of Russian assets that were frozen following the invasion of Ukraine.12

- 8World Bank (2025). «Ukraine: Fourth Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment Fourth Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment».

- 10See Z. Darvas and C. McCaffrey (2024). «Management of debt liabilities in the EU budget under the post-2027 MFF», European Parliament.

- 11We assume the following hypotheses in the detailed calculation shown in the chart: (i) the public sector finances a quarter of the 800 billion per year identified in the Draghi report as investment needs, while another 25% is covered by the EU budget through the Competitiveness Compass funds; (ii) the extra defence expenditure corresponds to pooled funding of 25% of an increase of 1 point of GDP, not including the needs already identified in the Draghi report (20 billion per year); (iii) the repayment of the NGEU pooled debt is in the range of 20-25 billion per year; (iv) we consider that half of the cost of rebuilding Ukraine (500 billion over the next 10 years, according to the World Bank) will be borne by European institutions and that, based on what has been observed to date, 50% will be pooled; (v) according to different sources, the cost of a possible eastward expansion would be around 20 billion per year for the EU budget; (vi) reallocation of 25% of the funds for the period 2021-2027; and (vii) the alternative funding considers the rollover of the NGEU pooled debt, the use of around 100 billion of frozen Russian assets and new internal funds amounting to 35 billion annually.

- 12K. Kowald and M. Pari (2025). «Future of EU long-term financing», European Parliament.

The road to the approval of a new MFF will not be free of obstacles. Internal political fragility has intensified after the latest electoral cycle, including the European Parliament elections in 2024. Also, the prospect of higher public spending could add tension to the sovereign debt markets,13 and it remains to be seen what socio-political bill will be left by the new European Commission’s apparent shift on environmental matters, with a climate agenda that is increasingly subordinated to the drive for competitiveness.

However, the Council’s unanimity in endorsing the European defence plan proposal, together with the recent green shoots in Paris-Berlin relations, has given cause for some optimism to pursue an ambitious budget that is up to the challenges of the time. Unlike the urgency that guided the historic agreements for NGEU in 2020, we now have the advantage that a thorough prior reflection on the EU’s priorities has been carried out through the Letta and Draghi reports, thus facilitating the selection of policy actions that can have a real impact and that are meaningful in the medium term for the 450 million Europeans.

- 13See the Focus «Germany’s fiscal shift and the bund: when security comes at a price» in this same Monthly Report.