NGEU funds: what can we say about their impact and future challenges?

Unlike the process of tracking the achievement of the milestones and targets laid out in the Recovery and Resilience Plans (RRPs), assessing where we are in their implementation becomes more complicated when we try to quantify their macroeconomic impact and their transformative capacity for the European economy. This is becoming more relevant given the challenges posed by the increasingly complex geopolitical scenario we face.

Unlike the process of tracking the achievement of the milestones and targets laid out in the Recovery and Resilience Plans (RRPs),1 assessing where we are in their implementation becomes more complicated when we try to quantify their macroeconomic impact and their transformative capacity for the European economy. This is becoming more relevant given the challenges posed by the increasingly complex geopolitical scenario we face.

- 1. See the article «NGEU funds: what is the status of their implementation at the European level?» in this same Dossier.

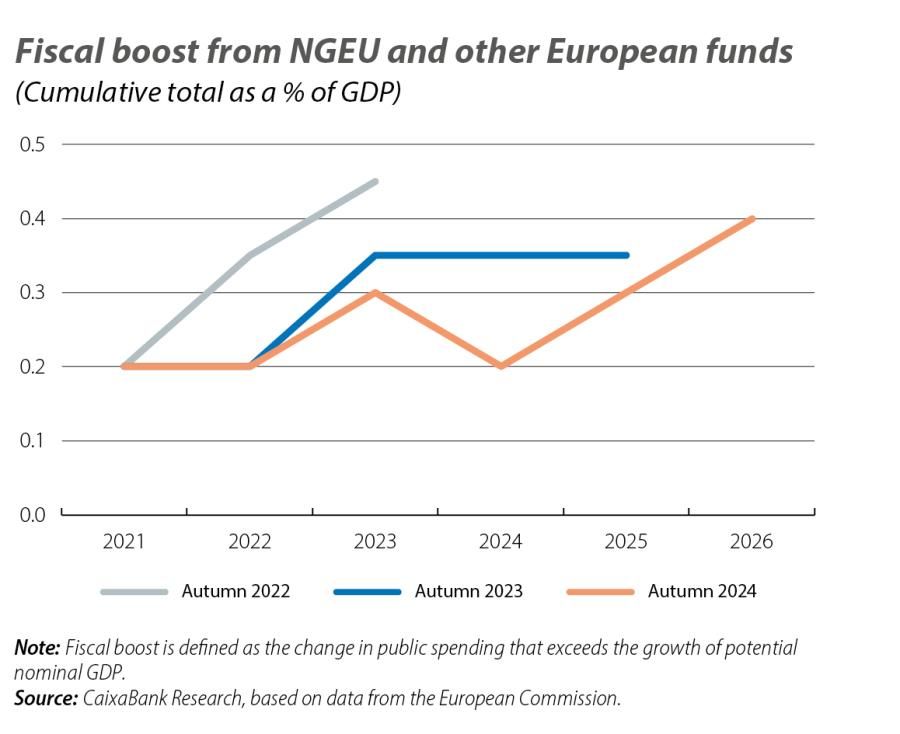

The European Commission has so far published two exercises projecting the impact of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). The first one, conducted in 2021 upon the approval of the RRPs, placed the peak impact on the level of GDP in 2026 within the 0.7%-1.2% range.2 The second, in 2023, was conducted to reflect the revision of the RRPs, to include a more realistic schedule of payments and to capture the impact of the energy shock following the invasion of Ukraine, placing this range at 0.9%-1.4%.3 These latest projections, which barely vary from the initial ones, have already become outdated because they do not reflect the slower than expected progress in the implementation of the RRPs – an aspect which the European Commission has shown in its biannual forecast cycle, in which it has revised downwards the fiscal momentum derived from public spending financed with European funds (see chart). In the same vein, the ECB recently estimated for the euro area that the impact on GDP had been just 10 or 20 basis points in the period 2021-2023, well below the 0.5% boost initially expected.4

- 2. See P. Pfeiffer and J. Varga (2021). «Quantifying Spillovers of Next Generation EU Investment», Discussion Paper nº 144, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN), European Commission.

- 3. The new EU-wide profile was published in the European Commission’s working paper which accompanied the mid-term evaluation of the RRF published in February 2024.

- 4. K. Bańkowski et al. (2024): «Four years into NextGenerationEU: what impact on the euro area economy», Occasional Paper nº 362, ECB.

In the medium term, the range of uncertainty is much broader. On the investment side, the RRF regulation establishes that all payment requests must be filed by 31 August 2026 – a deadline which, given the current rate of achievement of the milestones and targets, opens up unknowns about the final percentage of the funds that will actually be absorbed. Even in the case of the loans, which can be channelled in the form of financing for the private sector and therefore have an impact beyond 2026, there is a question as to what the actual demand for funds will be and to what extent this demand will be additional in nature.5 In any event, it seems that the fiscal boost alone will have a very limited macroeconomic effect in the medium term. The European Commission itself, in its latest projections on the RRF, estimated that the cumulative impact on the level of EU GDP in 2031 will be in the range of 0.3%-0.7%, similar to the figures estimated by the ECB for the euro area (0.2%-0.6%).

On the reform side, there is broad consensus on how much scope they have to boost GDP and the potential growth of the European economy.6,7 The mid-term evaluation of the RRF points out the highly additional nature of the reforms contained in the RRPs, as well as their contribution to further progress in the implementation of the country-specific recommendations proposed by the Council in the context of the European Semester. However, given their importance for assessing the transformative capacity of the RRF, it would be useful to shed more light on the time scale of the expected impact as well as on the quantitative effects, including their contribution to advancing the EU's climate, energy, digital and social goals for 2030. The ex-post evaluation envisaged in the regulation for 2028 would be a good opportunity to address these shortcomings in the systematic monitoring of the RRF. For the moment, the benchmark estimates in this field continue to be those of the ECB, which for the euro area anticipates an increase in potential growth in the medium term in the range of 0.1-0.2 pps, largely as a result of the boost to total factor productivity provided by the structural reforms.

- 5. i.e. whether NGEU funds will be used for purposes that would not have otherwise been covered in their absence.

- 6. P. Pfeiffer, J. Varga and J. In´t Veld (2023). «Unleashing Potential: Model-Based Reform Benchmarking for EU Member States», Discussion Paper nº 192, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN), European Commission.

- 7. K. Bańkowski et al. (2022): «The economic impact of Next Generation EU: a euro area perspective», Occasional Paper nº 291, ECB.

In the five years since the conception of the NGEU funds, both the European political landscape and the global geopolitical context have undergone major transformations. Various national elections and those held in the European Parliament in 2024 have increased the representativeness of Eurosceptic parties, with the new European Commission receiving the least support in the appointment of its members. The growing internal fragmentation complicates the political arithmetic in order for progress to be made with the European agenda and in tackling the challenges of the coming years. These challenges include the negotiation of the new multi-year financial framework for 2028-2034 and the deployment of the European Commission’s competitiveness plan, based on the recommendations of the Draghi report.8 Both of these elements should take over from the transformative momentum of the RRPs, particularly in areas that are still lagging far behind, such as the development and use of artificial intelligence, the excessive regulatory burden on companies and the absence of a single capital market.9

The international environment has also become more complex. In addition to the war in Ukraine, a country which borders the EU and with which accession talks have been initiated, there is now uncertainty – beyond the protectionist threat – in relations with the new Trump administration. The EU faces further global geopolitical fragmentation with deep strategic dependencies in the spheres of defence, technology and clean energy. These elements could mark a shift in the spending priorities in the final stretch of the NGEU programme, especially given the reduced fiscal margin for manoeuvre that is available to a large number of Member States.10 This will require the use of existing degrees of flexibility, including to seek a consensus that does not dilute the good aims defined in 2020.

- 8. See the Focus «Draghi proposes a European industrial policy as a driving force to address the challenges of the coming decades» in the MR10/2024.

- 9. See the articles of the Dossier «United in diversity: Europe’s economic challenges» in the MR06/2024.

- 10. See the Focus «The new EU economic governance framework» in the MR01/2025.

- 1. See the article «NGEU funds: what is the status of their implementation at the European level?» in this same Dossier.

- 2. See P. Pfeiffer and J. Varga (2021). «Quantifying Spillovers of Next Generation EU Investment», Discussion Paper nº 144, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN), European Commission.

- 3. The new EU-wide profile was published in the European Commission’s working paper which accompanied the mid-term evaluation of the RRF published in February 2024.

- 4. K. Bańkowski et al. (2024): «Four years into NextGenerationEU: what impact on the euro area economy», Occasional Paper nº 362, ECB.

- 5. i.e. whether NGEU funds will be used for purposes that would not have otherwise been covered in their absence.

- 6. P. Pfeiffer, J. Varga and J. In´t Veld (2023). «Unleashing Potential: Model-Based Reform Benchmarking for EU Member States», Discussion Paper nº 192, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN), European Commission.

- 7. K. Bańkowski et al. (2022): «The economic impact of Next Generation EU: a euro area perspective», Occasional Paper nº 291, ECB.

- 8. See the Focus «Draghi proposes a European industrial policy as a driving force to address the challenges of the coming decades» in the MR10/2024.

- 9. See the articles of the Dossier «United in diversity: Europe’s economic challenges» in the MR06/2024.

- 10. See the Focus «The new EU economic governance framework» in the MR01/2025.