Why does Europe need a Capital Markets Union?

Europe is facing not only a demanding economic situation, but also a trident of underlying challenges: the decarbonisation of the economy, the revitalisation of productivity and technological development, and the growing geopolitical fragmentation in the world. Addressing these challenges will not be possible without mobilising significant investment and financing, on the one hand, or without strengthening the international role of the euro, on the other. And this is precisely what the Capital Markets Union (CMU) is pursuing.

Is Europe falling behind?

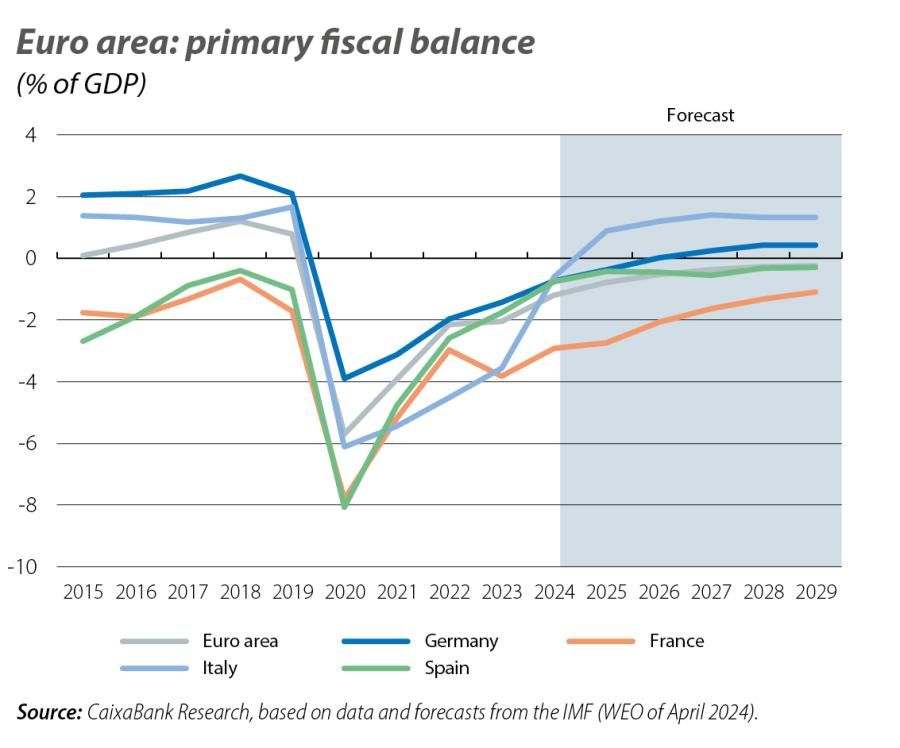

In order to tackle these underlying challenges, several estimates suggest that Europe will need to deploy between 0.5 and 1 trillion euros per year through to 2030.1 These additional investment needs, which are equivalent to the annual GDP of countries such as Austria or the Netherlands, arise in a context in which fiscal policy has less margin for manoeuvre, being weighed down by high public debt ratios, with underlying pressures on public spending (e.g. population ageing) and with the need for and the prospect of a gradual correction of budget deficits (see first chart). On the other hand, there is a large stock of private savings which is not mobilised and, for Europe’s purposes, it is vitally important to develop a strong common capital market,2 that is, a market in which savings and investment flow between all EU countries through bonds, shares and other financial assets.

- 1M. Demertzis, D. Pinkus and N. Ruer (2024), «Accelerating strategic investment in the European Union beyond 2026», Report 01/2024, Bruegel, and DG Trésor (2024), «Developing European capital markets to finance the future: Proposals for a Savings and Investment Union», Ministère de l’Économie, des Finances et de la Souveraineté industrielle et numérique. These figures include investments to decarbonise all economic sectors, transform the energy industry, address various environmental challenges, develop key digital technologies (communications, AI, semiconductors, etc.) and strengthen supply chains related to the defence industry.

- 2Enrico Letta talks about more than 30 trillion euros, largely stored in cash and deposits. Moreover, he estimates that around 300 billion euros of European households’ savings leave Europe each year (primarily destined for the US). E. Letta (2024), «Much More Than a Market», Report to the European Council.

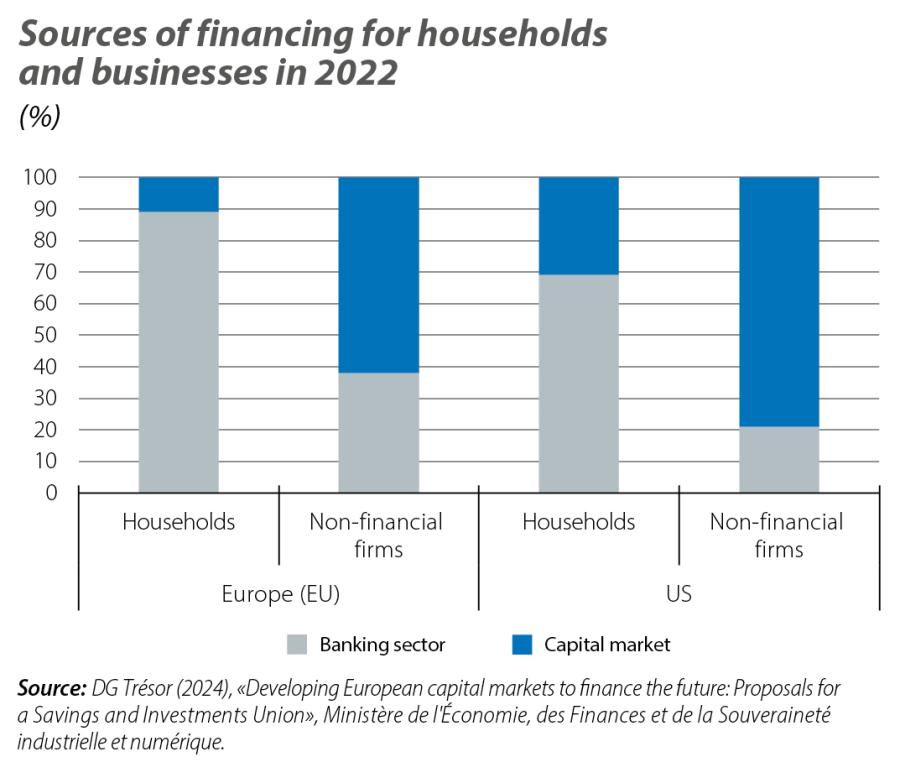

However, there is consensus that the European capital market is underdeveloped (see second chart). This can be seen in a long list of cases which, if read in positive terms, indicate the potential to mobilise funds that an effective capital markets union would allow to materialise. As an example, while the EU accounts for around 20% of the world’s GDP, its stock markets represent just 10% of global capitalisation, and within the technology sector there are just two European companies in the top 20 in terms of capitalisation. Moreover, the liquidity of Europe’s stock markets is lower than that of other regions (the US), especially in the case of so-called small-cap companies (which are younger and have greater growth potential). The emergence of tech firms also requires a developed venture capital market,3 which is currently too small in Europe (the size of Europe’s venture capital markets is only 20% of that of the US) and is also fragmented (portfolios have a significant national bias). European public and private bond markets are also relatively small (130% of GDP in the EU vs. 200% in the US). All this affects the cost of financing European companies, as well as their ability to expand, to the point that some start-ups born in Europe have ended up migrating to the US in search of funds.4 Similarly, Europe’s financial sector has been gradually losing market share with respect to its US counterparts, both in terms of asset management and in investment and corporate banking.5

- 3Innovation produces projects that are high-risk, offer uncertain returns and have few tangible assets to back them up. The venture capital industry has specialised in financing innovation, detecting and supporting the birth of tech firms with a high potential thanks to its governance system, with phased financing and active participation in the companies in question. See J. Lerner and R. Nanda (2020). «Venture capital’s role in financing innovation: What we know and how much we still need to learn», Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(3), 237-261.

- 4The European Investment Fund speaks of a «technology drain». See https://www.eif.org/etci/scale-up-financing-gap/index.htm.

- 5DG Trésor (2024) cited in footnote 1.

Background, current situation and outlook for the CMU

The CMU project was born a decade ago in the face of a combination of considerations, ranging from financial stability (e.g. reducing the fragmentation of European markets, increasing the capacity to absorb economic shocks and diversifying sources of business financing), to social justice (ensuring that all EU citizens have equal access to capital markets), to economic efficiency and ensuring the availability of financing for innovation and investment. However, as we have already seen, this initial ambition has not resulted in a significant development of the European capital market, nor has it led to an effective transformation of policies.

In fact, in 10 years the progress has been more incremental, rather than one of structural transformation.6 This is illustrated by the nature of the key milestones achieved to date, which include the so-called «single access point» (a facility that centralises and gives access to publicly available financial information on European companies and investment products, the legislative framework of which was formalised in December in 2023 but which will still take some years to be developed), the «European Long-Term Investment Fund» (ELTIF, which is a vehicle for channelling private capital towards investment in infrastructure and other long-term projects and enterprises, which the EU has tried to stimulate but without managing to raise significant amounts of capital so far) and a revision of the trading rules to improve transparency in financial instruments markets (MiFIR regulation and MiFID directive).

In the run-up to the European elections in June, which mark the beginning of a new term for 2024-2029, a number of voices have pushed for a reignition of the CMU project. In March, both the Eurogroup and the ECB launched manifestos to develop the CMU with an agenda of concrete measures related to developing markets (e.g. asset securitisation), supervision and regulation (advocating a direct role of European supervisory agencies and reducing the regulatory burden) and European harmonisation of national regulations and frameworks (in areas such as insolvency, accounting, debt issuance, collateral management, securities markets, etc.), among other initiatives.

The CMU joins a list of European economic integration projects that remain incomplete. These include the Banking Union, as negotiations on the European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS) remain at an impasse,7 and the ESM reform, which was agreed in 2021 but is not yet effective.8 The difficulty of all these initiatives is that, when the integration being pursued is ambitious (whether a European deposit guarantee scheme or harmonising insolvency and accounting frameworks), it is necessary to overcome a clash between national jurisdictions and pan-European authorities. This requires political capital and/or an environment that rewards change. And therein lies one of the intrinsic difficulties of the underlying transformations: the green and digital transitions and geopolitical fragmentation are formidable challenges, but in the short term their severity is not felt to the same degree as other crises that are more short-term in nature and in which the threat to Europe’s survival is so palpable that the inertia and resistance to change can be overcome. The question, therefore, is how much political capital the 2024-2029 European term will be able to garner.

- 6N. Veron (2024), «Capital Markets Union: Ten Years Later», In-depth analysis, PE 747.839, requested by the ECON Committee (European Parliament).

- 7The EDIS would protect the bank deposits of euro area citizens, regardless of which European country they are located in, and it would do so more evenly than the current national system for guaranteeing deposits. This would help to weaken the national link between the public sector and the financial system (the so-called doom loop, which amplifies and exacerbates economic recessions) and would help economic shocks to be better absorbed, thus improving the effectiveness of all economic policies.

- 8

It is yet to be ratified by the Italian Parliament. The ESM reform is intended to bolster the European Stability Mechanism, strengthening its role as a backstop in the event of bank resolutions, facilitating access to its credit lines and assigning it a greater role in country support programmes (alleviating the burden of the Troika [ECB, IMF and European Commission]).