The exposure of consumer goods in Spain to international agricultural commodity prices

We measure how intensely and for how long the rise in agricultural commodity prices is spreading throughout the food chain: from international agricultural prices, to the prices received by farmers in Spain and, finally, to consumer prices.

Since the beginning of 2021, we have witnessed a global escalation in agricultural commodity prices, triggered by three factors: (i) the revival of the world economy following the pandemic, (ii) temporary declines in global production (droughts, insect plagues and livestock diseases) and (iii) the outbreak of the war in Ukraine.

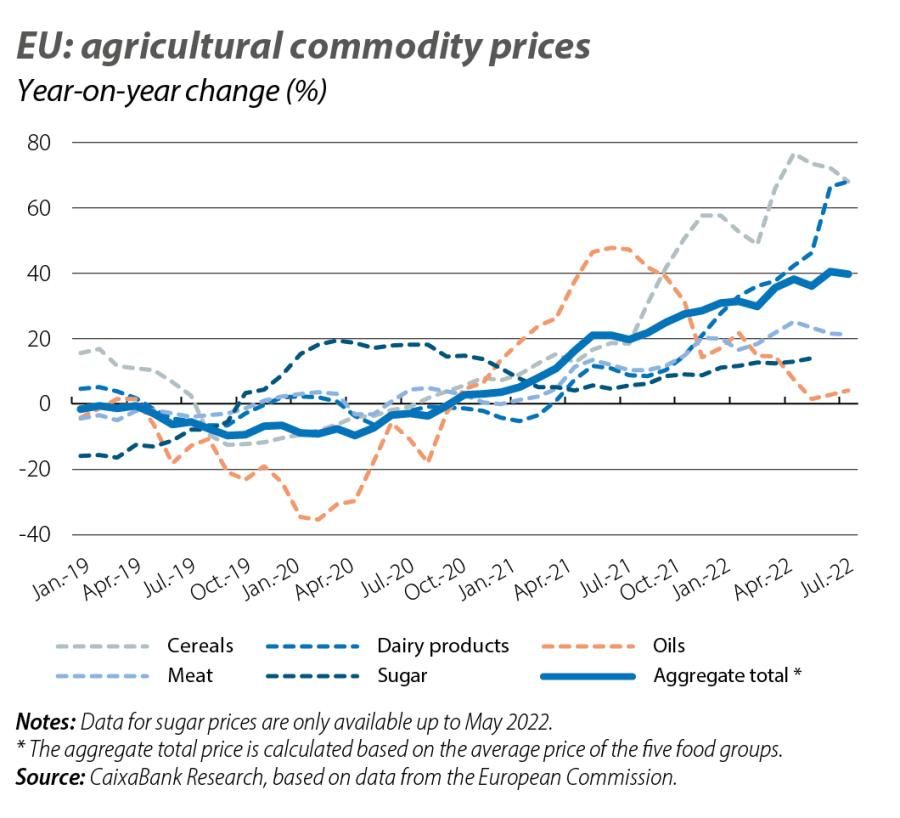

As the first chart shows, agricultural prices in the EU grew at a rate of 39.7% year-on-year in July 2022. This is explained by a rise in all five of the groups of food products we have analysed, with the biggest price rallies occurring in cereals (68.3%) and dairy products (68.0%), while oils grew at a more moderate rate of 4.1%. This increase in prices, together with the rising energy prices, has gradually filtered throughout the food chain, resulting in an increase in the final consumer prices of foods. Thus, in July, the food component of the Spanish CPI rose by 12.4% year-on-year (11.9% in the case of processed foods and 13.4% for fresh foods), contributing 3.3 pps to headline inflation (10.8% in July).

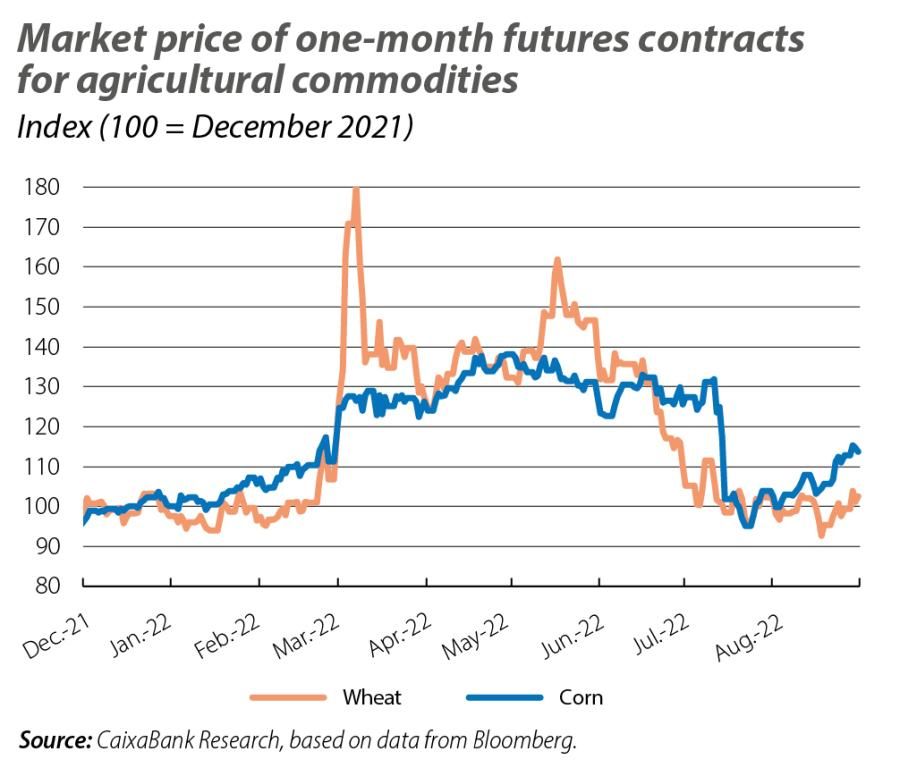

It should be noted that the latest fluctuations in the price of agricultural commodity futures on the international markets point to a reduction in inflationary tensions. For instance, wheat and corn futures, as measured by their price on the Chicago Board of Trade, have moderated to levels similar to those seen at the beginning of the year (see second chart). The transmission of these declines in international prices to internal EU prices is not occurring instantly, due to the effects of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).1 Nevertheless, a slight moderation in prices is becoming apparent in July, with the average price of the groups of food products included in the first chart falling by 1.7% month-on-month, the first drop in 12 months.2

- 1. The CAP includes a set of interventions (direct subsidies, price support mechanisms and guaranteed minimum prices) that affect the prices of agricultural commodities in the EU. See the article mentioned in footnote 3 of this same Focus.

- 2. For a description of the evolution of the price of agricultural commodities in the international markets, see the Focus «The dance continues in the commodity market» in this same report, as well as the forthcoming Agrifood Sector Report.

To shed some light on this question, we used an econometric model to measure the intensity and duration of the translation of agricultural commodity prices through the links that make up the food chain: from international agricultural prices, to the prices received by farmers in Spain and ending in consumer prices.3 For EU countries, the analysis must be carried out using the internal prices of the single market for the commodities in question, which already incorporate the effect of the CAP.

The third chart shows the impact on the food CPI of a 10-pp shock in the month-on-month rate of change in agricultural commodity prices in the EU.4 The results suggest that the shock produces an 0.6-pp increase in the month-on-month change in the food CPI after two months, an apparently small impact. However, this shock has a highly persistent effect on food consumer prices, as they would continue to reflect a significant impact for eight months. Thus, the cumulative effect of the shock after 12 months would amount to 2.3 pps (0.5 pps for the headline CPI), illustrating just how exposed the food CPI is to international commodity prices.5

- 3. This analysis is based on the article «El aumento de los precios de las materias primas alimenticias y su traslación a los precios de consumo en el área del euro», by F. Borrallo, L. Cuadro-Sáez and J.J. Pérez, Bank of Spain, Economic Bulletin 3/2022 (content available in Spanish). We estimate a first-order vector autoregressive model (VAR) for each food product (cereal, dairy, meat, oil and sugar), incorporating in each case the month-on-month rate of change in the price of the commodity in question in the EU, the price received by farmers in Spain and the CPI component. The data used are taken from the period between April 2005 (September 2006 in the case of sugar) and February 2022.

- 4. The results of the five food groups analysed are aggregated using their relative weights in the CPI.

- 5. Between August 2021 and April 2022, the average month-on-month rate of change in the prices of these five agricultural commodities in the EU was 2.9%, compared with 0.1% on average for the period 2010-2019.

Using these sensitivities, we simulated how the food CPI would have evolved in the absence of commodity shocks since January 2021. According to our estimates, food prices would have risen by 2.7% between January 2021 and July 2022, a figure significantly lower than the 13.0% rally actually observed during that period. It can thus be concluded that most of the increase in food prices in Spain is attributable to the external shock of rising agricultural commodity prices. On the other hand, if we assume that from August onwards there will be no further disturbances affecting agricultural commodity prices or the cost of their production and consumption, the inflation of the food component of the CPI would gradually fall to 10.4% in December 2022 (2.0 pps below the July rate), once again revealing the shock’s highly persistent nature. During 2023, the moderation in food inflation would intensify, reaching slightly below 2% in the second half of 2023 (see fourth chart).

- 1. The CAP includes a set of interventions (direct subsidies, price support mechanisms and guaranteed minimum prices) that affect the prices of agricultural commodities in the EU. See the article mentioned in footnote 3 of this same Focus.

- 2. For a description of the evolution of the price of agricultural commodities in the international markets, see the Focus «The dance continues in the commodity market» in this same report, as well as the forthcoming Agrifood Sector Report.

- 3. This analysis is based on the article «El aumento de los precios de las materias primas alimenticias y su traslación a los precios de consumo en el área del euro», by F. Borrallo, L. Cuadro-Sáez and J.J. Pérez, Bank of Spain, Economic Bulletin 3/2022 (content available in Spanish). We estimate a first-order vector autoregressive model (VAR) for each food product (cereal, dairy, meat, oil and sugar), incorporating in each case the month-on-month rate of change in the price of the commodity in question in the EU, the price received by farmers in Spain and the CPI component. The data used are taken from the period between April 2005 (September 2006 in the case of sugar) and February 2022.

- 4. The results of the five food groups analysed are aggregated using their relative weights in the CPI.

- 5. Between August 2021 and April 2022, the average month-on-month rate of change in the prices of these five agricultural commodities in the EU was 2.9%, compared with 0.1% on average for the period 2010-2019.