What is behind the rise in oil prices?

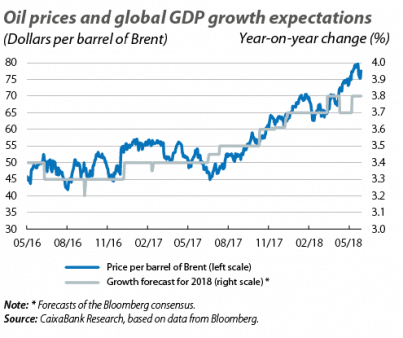

The price of oil has risen by more than 70% over the last 12 months, from 45 dollars per barrel of Brent in June 2017 to nearly 80 dollars in May 2018. So, after three years of low prices, crude oil has returned to levels not seen since late 2014. What are the forces behind this rise in oil prices? Could it compromise the growth of the global economy? We analyse this question below.

The factors behind the rise in oil prices

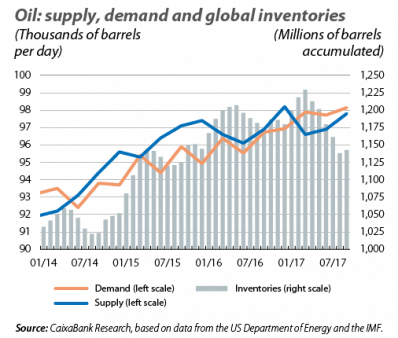

In early 2017, the oil market was in a situation in which supply persistently exceeded demand and, therefore, a significant buffer of crude oil stocks had accumulated (see first chart). However, the price of Brent oil had recovered from the declines seen in 2014 and 2015 and it had stabilised at around 55 dollars per barrel. On the one hand, this recovery was a result of the agreement reached between OPEC and other large producers, such as Russia, in November 2016 to cut production.1 On the other hand, the accumulated stocks provided a buffer which reduced the volatility of the oil price, isolating it (partially) from the episodes of geopolitical instability.

From June 2017, however, oil prices began to increase sharply, driven by factors related to both supply and demand. On the supply side, the first chart shows how the agreement reached between OPEC countries and their partners to cut production succeeded in containing, and even reducing, the global oil supply. What is more, the cuts in oil production have clearly exceeded those agreed, as shown in the second chart.2 As this reduction in the supply pressured prices up, US crude oil production was expected to surge and thus contain the price of Brent oil between 50 and 60 dollars. However, in the last few quarters, the US oil infrastructure has been constrained by bottlenecks and has not been able to offset the impact of the OPEC cuts.3

To add to the restriction of supply, on the demand side global economic growth surprised on the upside and led to a significant upward revision of growth forecasts. In fact, the third chart shows a very clear association between the increase in the price of oil and the improvement in the outlook for global GDP. Finally, the combination of these dynamics of supply and demand led to a substantial depletion of the buffer in crude oil stocks, which would explain the increased volatility in the price of oil and its renewed sensitivity to geopolitical risks. Following on from this, it is likely that the recent reintroduction of economic sanctions on Iran has also contributed to the rise in the price of oil (not only through the direct impact it will have on the country’s oil exports, but also by increasing the risk of geopolitical conflicts in the Persian Gulf region).

Despite the fact that there is consensus on the role played by all of these factors, their relative importance is not clear and quantitative estimates on this matter vary considerably depending on the methodology used. For example, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York breaks down oil price fluctuations into factors related to supply and demand, based on their relationship with a whole range of financial variables. Its results, which we reproduce in the fourth chart, indicate that demand is responsible for nearly 50% of the price increase, while supply would explain 20% of the increase (the model attributes the remaining 30% to other factors it cannot explain). On the other hand, based on the analysis of production and consumption of oil in the past and of the accumulation of stocks (which reflect expectations about the future balance between supply and demand), the ECB has recently estimated4 that supply factors are responsible for slightly more than 60% of the surge in price, while 30% of the increase is down to global demand, and the depletion of stocks would have tended to push prices slightly downwards.

Consequences for growth

The impact of higher oil prices on global growth will depend on two elements: i) the factors responsible for the movement (supply, demand, or others) and ii) the balance between the positive impact on oil-exporting economies and the negative impact on importers of crude oil. Traditional estimates, such as those by the IMF which we share in the fifth chart, implicitly assume that the negative consequences on importers of oil (with a higher marginal propensity to consume) have far outweighed the positive effect on the income of oil exporters. However, whereas these estimates have focused on analysing the consequences of a reduction in oil supply, we have just seen that factors related to demand have also played an important role in the recent trends and, therefore, can mitigate the negative impact of the rise in the price of oil. In this regard, the 2014 empirical study by Cashin et al.5 shows that an increase in the oil price due to factors related to demand is associated with increases in economic activity in both oil-exporting and oil-importing economies, since it is the result of a positive momentum in the global economy.

Finally, in addition to the mitigating effect of demand, there have been other changes in the traditional transmission mechanisms. Firstly, oil has become less important in the global supply chain, both due to GDP being less energy-intensive and due to oil accounting for a smaller portion of the total energy consumed. Secondly, the oil-exporting economies currently have smaller fiscal buffers, meaning that their propensity to spend the additional revenues generated from oil may be greater. Finally, the irruption of the shale sector in the US has resulted in much of the US economy now benefiting from higher oil prices.

On the whole, all these elements suggest that the impact of rising oil prices on the global economy could be less significant than traditionally expected, and they also help to explain why global GDP has remained strong in recent quarters.

1. For an analysis of the agreement and what caused it, see the Focus «The oil producer agreement: the cartel is back» in MR01/2017.

2. Part of the reason for the agreed production cuts being exceeded is the major economic crisis which Venezuela has been suffering from and the collapse of its oil production: in May 2018, the country supplied 600,000 barrels per day less than in May 2017.

3. See R.S. Kaplan (2018) «A Perspective on Oil», speech of 19 June.

4. See I. Alonso and F. Skudelny (2018), «Are the recent oil price increases set to last?» in the ECB’s 02/2018 Economic Bulletin.

5. Cashin et al. (2014), «The Differential Effects of Oil Demand and Supply Shocks on the Global Economy», Energy Economics.