Debt limits

In the coming years, the paths of interest rates and nominal GDP growth will create an environment in which it will not be so easy to regain fiscal space without a proactive effort by governments.

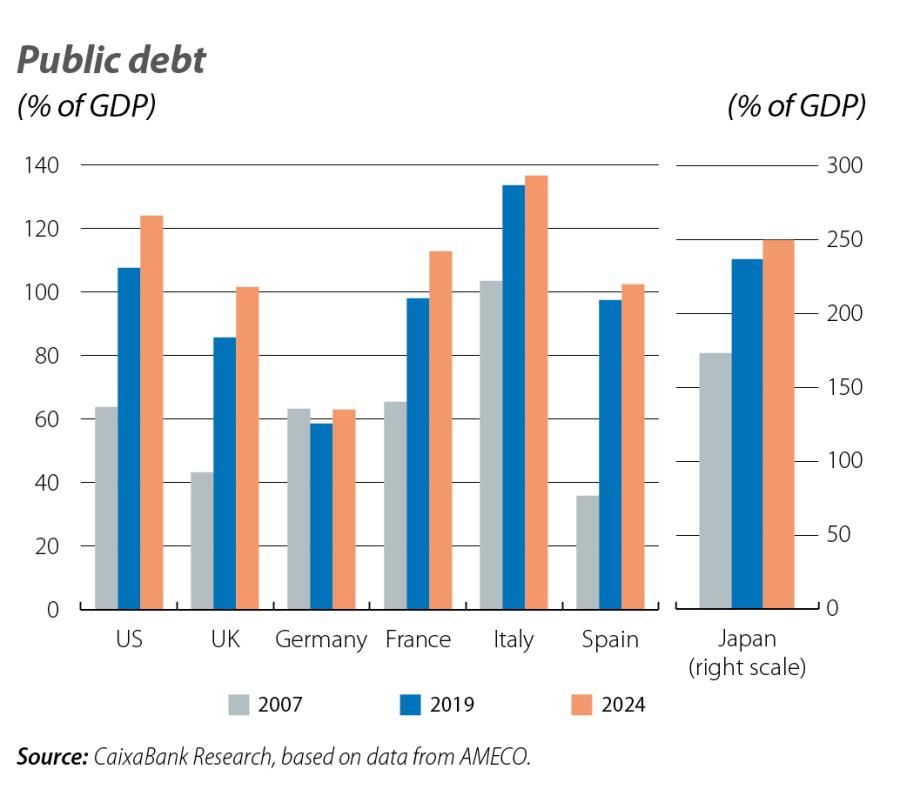

With the post-pandemic normalisation process now consolidated, and as we approach the end of the inflationary crisis, concerns are re-emerging about the levels of public debt (see first chart), as are calls for a realignment of the public finances and for the rebuilding of buffers to give fiscal policy margin for manoeuvre when necessary.

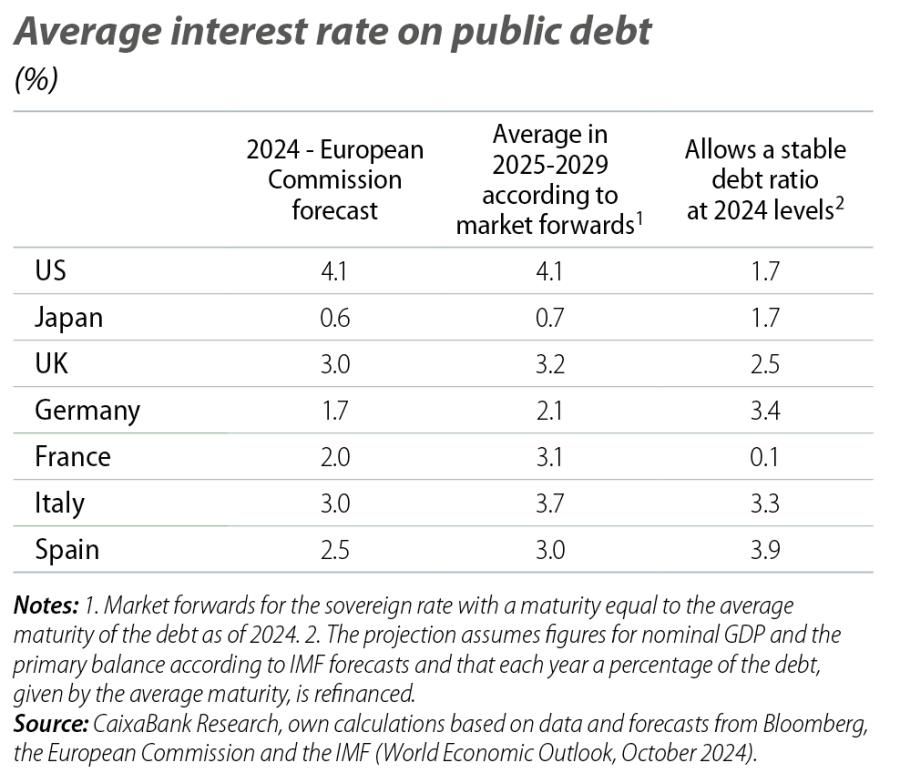

However, the process of recovering this fiscal margin faces significant obstacles in the current environment. On the one hand, and beyond the cyclical easing of monetary policy, in the medium term interest rates are expected to fluctuate somewhat above the levels anticipated a few years ago,1 increasing the average cost of public debt. On the other hand, the medium-term economic growth potential is shrouded in uncertainties, ranging from the question of artificial intelligence and its effects on aggregate productivity to the consequences of a less globalised and/or more fragmented world in the economic sphere. Moreover, population ageing, geopolitics (with associated defence spending needs) and investments for the energy transition and adapting to climate change will put increasing pressure on public finances. Added to all this is the inertia of public spending for «political economy» reasons.

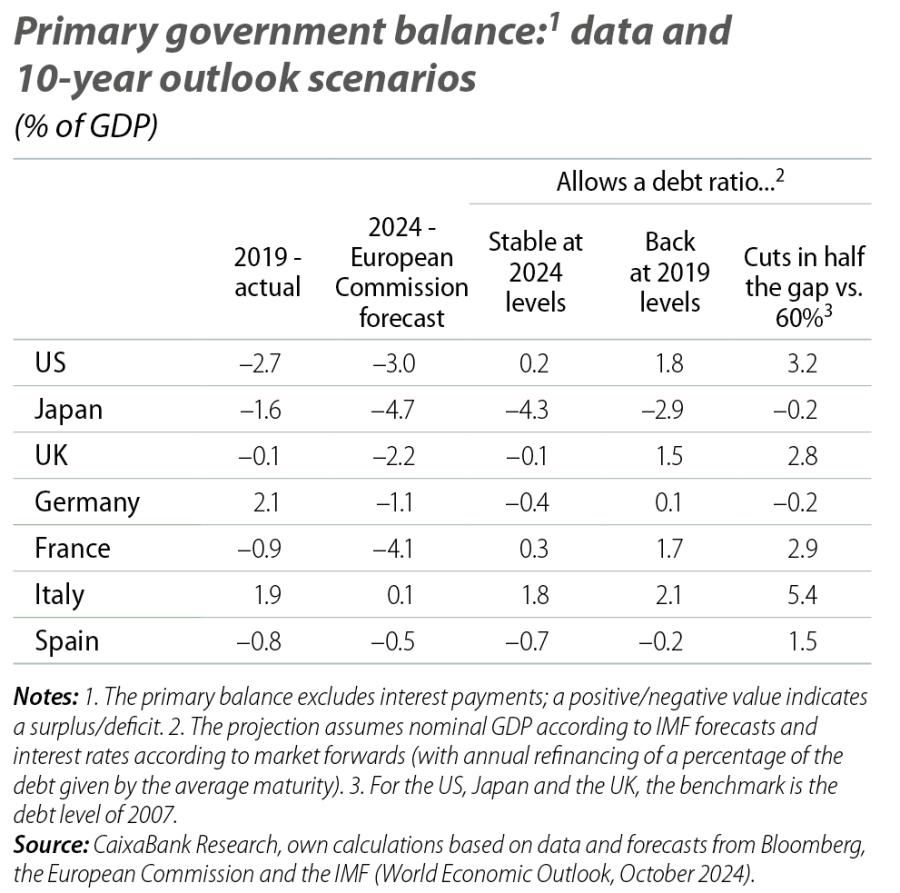

All these ingredients can be applied to the four main factors that determine the path of public debt: the starting level of debt, interest payments, the primary government balance2 and GDP growth. In this way, we can see how wide or narrow the path to rebuilding fiscal buffers is under different economic scenarios. We will do this with a simple sensitivity analysis on debt dynamics.3,4

Firstly, taking into account the relative moderation of nominal GDP growth as outlined by the latest IMF forecasts, together with the slow but steady rise in interest payments anticipated by the financial markets, in the first table we show the minimum primary balance which, if sustained for 10 years, would allow different levels of debt to be reached.5 This suggests that, compared to 2024, a degree of fiscal adjustment is required in order to smoothly stabilise or correct the levels of debt in the major economies, although the effort would be moderate (balances similar to those of 2019) in most cases. However, a more substantial recovery of fiscal room would require significant fiscal effort, surpassing that made in 2015-2019.

- 1For example, at the end of 2019, market forwards for 2030 indicated

a 10-year Spanish sovereign rate of around 2%, whereas now they place it close to 4%. This increase is widespread among the major economies and reflects a shift in the view regarding the structural level at which long-term interest rates are expected to settle. See, for example,

I. Schnabel (2024), R(ising) star?, speech at the conference The ECB and its Watchers XXIV. - 2I.e. the fiscal balance (total fiscal revenues minus total public expenditure) excluding net interest payments.

- 3The evolution of the debt-to-GDP ratio, d, is given by:

\({{d_t}_+}_1=d_t+\frac{{i_t}_{{}_+1}-g_{{}_t+1}}{1+{{g_t}_+}_1}d_t-b{{{}_t}_+}_1\)

where i is the average nominal interest rate on debt, g is nominal GDP growth and b is the primary government balance. - 4This analysis does not take into account feedback between the fiscal balance, GDP and interest rates. In reality, if an economy imposes a path based on, say, its fiscal balance, this will affect the path of its GDP and rates.

- 5

For each country, we simulate the debt ratio between 2025 and 2034 using the equation in note 3. The forecasts for nominal GDP growth (g) are taken from the IMF’s World Economic Outlook of October 2024 (we assume that the growth rate of 2029, the last available year, persists in 2030-2034). The interest rate on debt evolves as the rates on refinanced debt are updated with the average sovereign rate projected by market forwards as of late November 2024.

In the same vein, if we assume that the primary balance and nominal GDP evolve according to the latest forecasts published by the IMF, the second table shows us the average cost threshold above which debt dynamics would destabilise. This exercise shows that the IMF maintains a positive outlook for the public accounts in Spain and Germany, given that the fiscal path envisaged by the IMF allows for a reduction of debt, even if interest rates end up higher than those expected by the market, given the headroom available. However, the IMF’s outlook for the rest of the major advanced economies is less favourable, especially in the cases of France and the US, where the fiscal paths envisaged by the IMF would only stabilise the debt if interest rates were to end up being much lower than the market currently anticipates.

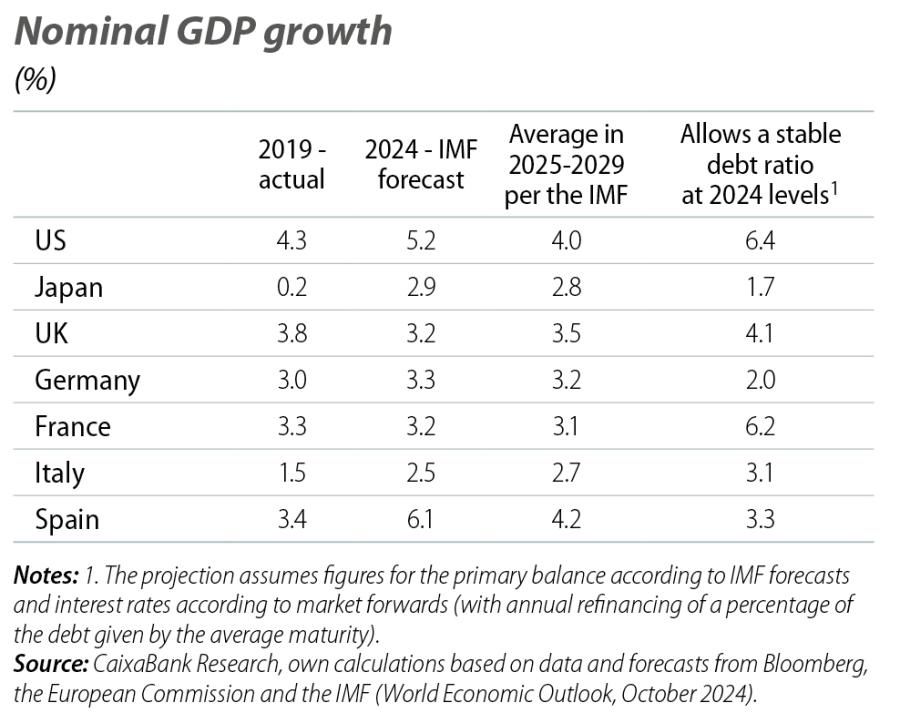

Finally, the third table shows the minimum nominal GDP growth that is required in order to avoid a deterioration in debt dynamics if the primary fiscal balance paths predicted by the IMF and the evolution of interest rates projected by the financial markets materialise as expected. Just as in the second table, this exercise reflects the IMF’s positive view of Spain and Germany, while the fiscal paths of the US and France would once again require a significant acceleration of nominal GDP to keep their levels of debt stable.

These three exercises also highlight the particularities of Japan. Unlike the other large economies, Japan’s debt dynamics continue to benefit from the margin provided by low interest rates. Moreover, according to the IMF, it is the country for which nominal GDP growth is expected to experience the greatest revival, and this would give it extra support in recovering fiscal space. However, despite these tailwinds, its debt ratio is much higher than other economies.

In short, this simulation of different scenarios for debt dynamics confirms that, over the coming years, the paths of interest rates and nominal GDP growth will create an environment in which it will not be easy to regain significant fiscal space unless governments make a proactive effort.