Germany: reinventing itself amid a new reality

The euro area’s largest economy is facing difficult times and a weak growth outlook. Its model is threatened by the slowdown in world trade, tariff wars, the change in the energy model and the emergence of new rivals.

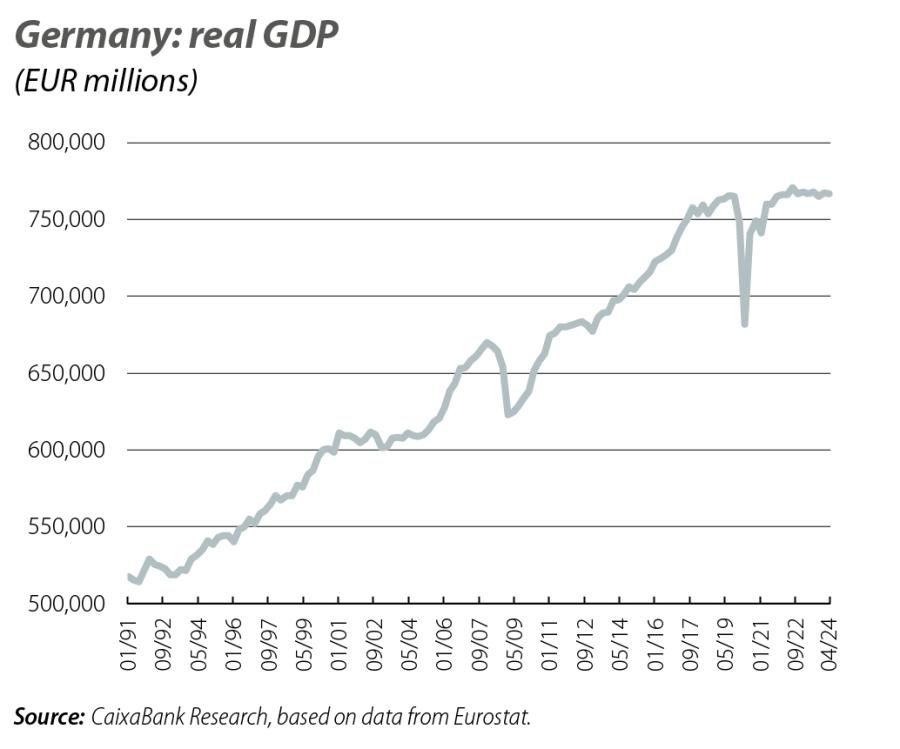

Germany, the euro area’s largest economy, is facing difficult times and a weak growth outlook. For many years, the strength of its economy was due to the success of policies aimed at promoting SMEs, its ability to produce high-quality goods (especially cars), cheap energy supplies and a highly export-oriented economy. This model, however, is threatened by the slowdown in world trade, tariff wars, the change in the energy model and the emergence of new rivals. In fact, Germany was the only economy in the G7 to go into recession in 2023 and, given the weakness it has been showing so far this year, we cannot rule out the possibility of it doing so again in 2024. During the decade of 2010-2019, Germany was one of the most dynamic economies, with an average growth of 2.0%. Since 2020, however, it has been practically stagnant, with only Estonia and Finland performing worse in the euro area. In fact, in Q3 2024, the German economy exceeded its pre-COVID level by only 0.2%, while France is already 4.1% above the level of Q4 2019, Italy is up 5.5% and Spain 6.6%. There are several elements that explain what is happening in Germany.

Dependencies and dependencies with rivalry: gas, China and cars

Germany has been one of the economies hardest hit by the war in Ukraine as it has lost its supply of cheap Russian gas (which accounted for over 50% of its pre-war gas imports). The increase in energy costs (40 euros/kWh currently vs. less than 20 euros/kWh in 2010-2020) has put its industry at a disadvantage compared to other countries with more diversified energy markets. Moreover, the phasing out of nuclear energy, within the framework of the decarbonisation of the economy and the transition to renewable energies amidst an energy crisis, further increased costs for businesses. Thus, the most energy-intensive industries1 are operating with activity levels almost 15% lower than prior to the war and some have moved part of their production abroad.

In addition, over the last decade Germany has developed close trade ties with China: it is the fourth largest

market for German exports and the main source of all its imports. However, the trade relationship with China has evolved over time. Whereas at first Germany imported intermediate, capital and consumer goods and exported final products with the «made in Germany» stamp of quality (cars, machinery, chemicals, etc.), not only is China now able to produce many of the goods it previously acquired from Germany, but also, in some cases such as cars, it has become a serious rival. In less than six years, China has gone from having little relevance in the global automotive market to accounting for almost 16% of all exports of electric or hybrid vehicles, and almost 7% of internal combustion vehicle exports. In particular, the number of vehicles exported by China is more than double that exported by Germany in 2024 to date. This surge has been largely due to a highly aggressive pricing strategy, supported by significant public aid and subsidies provided by the Chinese government to its industry which exceed those implemented in other industrialised economies.

The increase in protectionist policies and the changes to global supply chains forced by the COVID pandemic pose an additional challenge for an economy as export-oriented as Germany’s. Europe in general, and Germany in particular, are focusing on de-risking strategies,2 and this entails enduring short-term difficulties as supply chains are restructured in order to reduce their dependence on imports from China and seek other European and non-European suppliers.

Low public investment and population ageing

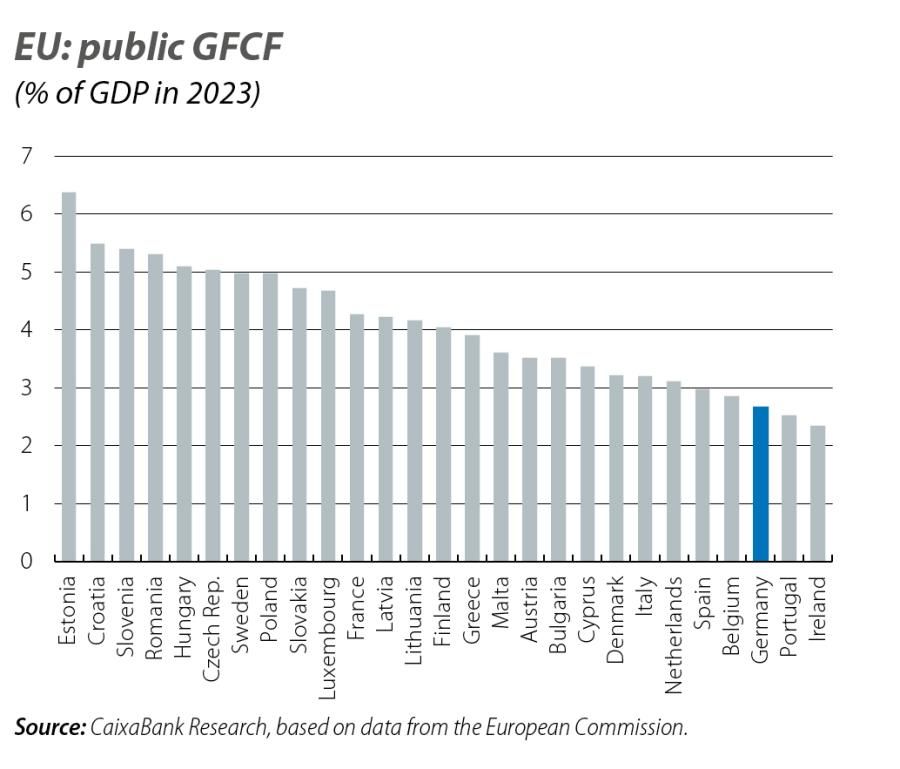

On the other hand, Germany has an almost structural deficiency in public investment. Despite rising in the last decade, gross fixed capital investment is expected to still lie below 3.0% of GDP in 2024, placing Germany among the bottom three in the EU ranking for this measure. Successive governments have been reluctant to increase public spending and have sought policies consistent with achieving a positive fiscal balance;3 so much so that in 2009 the constitution was amended to include a fiscal rule, known as the «debt brake», which limits the annual structural deficit to 0.35% of GDP, unless there are exceptional circumstances. This debt brake was put on hold after the COVID outbreak in 2020, and this pause was extended with the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. However, in 2024 it was reactivated and this has significantly reduced the margin for investing in the energy transition, digitalisation and defence.

This commitment to fiscal orthodoxy has enabled Germany to enjoy sound public accounts: the country’s fiscal deficits meet the 3.0% of GDP target and its debt is almost at the 60% threshold. Added to this strong fiscal position is the high level of savings accumulated by the private sector (more than 28% of GDP), which has allowed the current account balance to register a continuous surplus since 2002. The current account balance is also the highest in the euro area at present (and the second highest in terms of GDP), making it a significant potential source of friction with Germany’s trading partners, especially the US. Moreover, as noted in the Letta report, these savings flow out of the country, which has led to Germany presenting a net creditor position (foreign financial assets in the hands of Germans less German liabilities in the hands of non-residents) of 60% of its GDP.

Finally, Germany faces a major demographic challenge, even in the short term: according to estimates by the European Commission, the working-age population (between 20 and 64 years) will fall by more than 6% by 2035; this is almost twice as much as the decline expected in Italy and contrasts with the anticipated increases of more than 3.0% and 1.8% in France and Spain, respectively.4 This decline in the working-age population will intensify over the coming decades (likewise in the rest of the euro area), adding another obstacle to raising the economy’s potential growth in the medium and long term.

Reforms in an environment of opportunities provided by Europe

Germany therefore needs to implement an ambitious agenda of economic reforms that will enable it to overcome the significant challenges it faces, and it has significant strengths to help it achieve this. Germany is among the leaders of the business climate rankings, with strong and reliable institutions and political stability that favour business investment. Its geographical position, in the centre of the EU, also favours it and it is the home of key industrial conglomerates (machinery, manufacturing, electronics, chemicals, automotive, etc.).

In addition, now is a good time to initiate these reforms. On the one hand, the indebtedness of the country’s private sector is quite low and it is in a very strong fiscal position. This would allow it to design a fiscal strategy that assures the sustainability of the public accounts in the medium term, while adjusting the debt brake clause to allow for more rapid increases in public spending.5 On the other hand, Europe is immersed in the decarbonisation and digitalisation of its economy, a process epitomised by the NGEU funds. In addition, the Draghi report stresses the need for further progress to be made in this direction and lays the foundations for developing a new industrial policy at the European level.6

Despite the reluctance with which the Draghi report was received, the German government is aware of the delicate situation which the country finds itself in: the German car manufacturer Volkswagen, after publishing a 64% decline in net profits in Q3, announced for the first time in its history the closure of three plants on German soil. To make the outlook even more challenging, the coalition government has broken down as a result of stark differences over the key proposals to stimulate the German economy and the 2025 budget (still pending in parliament). After announcing the collapse of the coalition, Chancellor Scholz said he will call a vote of confidence on 15 January, paving the way for early elections in March (currently scheduled for 25 September 2025).