2025 global outlook: in search of a new normal

2025 will be a year in search of a new normal, threatened by the division between economic blocs. The best outcome would be to regain multilateral cooperation in order to tackle the new challenges and spread the risks together.

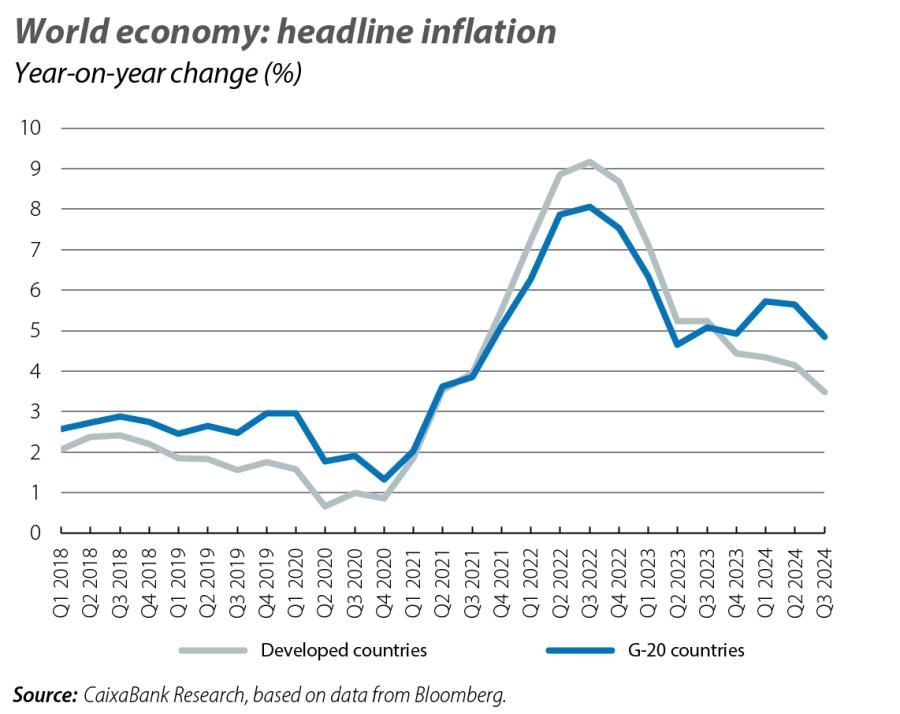

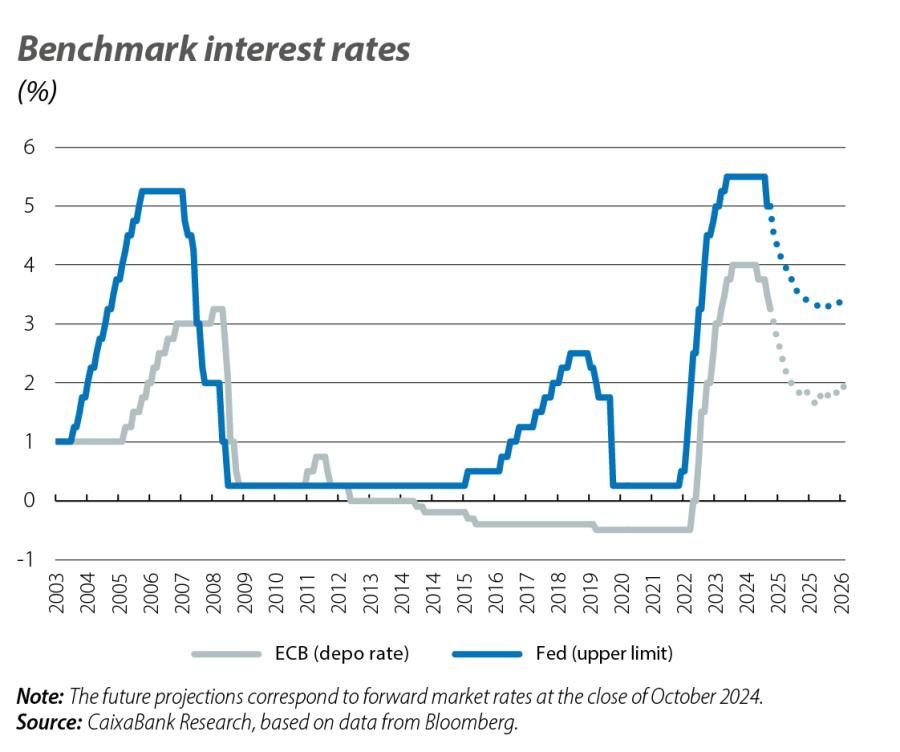

Five years after the outbreak of the pandemic – the origin of the imbalances and challenges that the international economy has been facing ever since – the feeling (or at least the hope) is that in 2025 we could see a certain degree of normality return to the pattern of the global economic cycle. Such a return to normality – understood as the closing of the gap between supply and demand that has been present in much of the last five years – will allow inflation to converge on the central banks’ target rates, and this would lead to an acceleration in the lowering of interest rates towards neutral territory (2% in the euro area and 3% in the US). If we add to the above an oil market which, besides the volatility that geopolitics will continue to transmit, appears to have an equilibrium price in the 70-80-dollar range, we would have a good support base for the consolidation of a soft landing of the world economy.

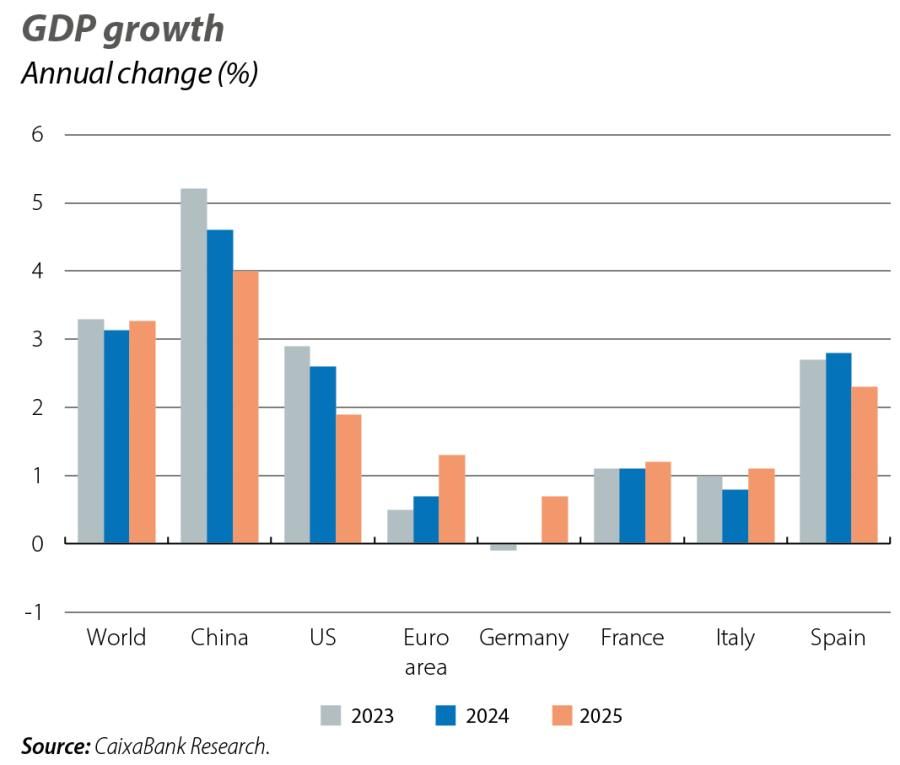

Therefore, it seems that the monetary imbalances caused by the wide variety of shocks that have accumulated in recent years could be on a path to correction, once the surprising and intense inflationary process that was triggered following the pandemic is under control. In this regard, the IMF anticipates that world inflation may fall to 3.5% by the end of 2025 (9.4% in 2022), slightly below the 2000-2020 average (3.6%). Most importantly, the return to price stability is being achieved without having to pay an excessive cost in terms of jobs and economic activity, as the resilient global cycle will maintain a cruising speed slightly above the 3% mark, with most labour markets still generating jobs. The less positive aspect of the macroeconomic outlook is that the recent divergences could become entrenched, both between sectors (the services sector outperforming industry) and between economic areas (the US outperforming the euro area and China) or regions (Germany being the major source of Europe’s problems).

Now that the fog of inflation that has been shrouding the business cycle has dissipated, the economic picture once again reveals old problems inherited from the great financial crisis, such as low potential growth, high levels of global public debt (over 100 trillion dollars) and mediocre productivity, especially in Europe. The magnitude of the structural challenges is even greater if we consider that they will need to be addressed in an environment subject to high uncertainty, both because of the underlying rise in geopolitical risk and due to the effects of

the process of transforming global trade relations, with supply chains becoming more regional and the world fragmenting once again into different blocs.

In this context, economic policy will have to address these medium- and long-term challenges with a limited degree of freedom on the fiscal side, while digesting the unconventional policies implemented by the central banks and a renewed role of industrial policy. Moreover, all this is taking place while we still have more questions than answers about what happened in the last four years in areas such as the behaviour of inflation expectations, the relationship between employment and prices (a steepening of the Phillips curve) or how supply shocks are distributed between wages and margins. This will make it difficult to anticipate the level at which real interest rates will stabilise or whether inflation will show an asymmetric pattern relative to the target. It will therefore take time for the changes of recent years to be fully digested, but as the IMF has just reflected at its autumn meeting, economic policy will need to pivot towards a triple target: a monetary policy that transitions from restrictive to neutral territory (good news for emerging markets), a fiscal policy that seeks to stabilise the debt dynamics (a particularly challenging task in the US and China) and more decisive supply policies aimed at boosting potential growth. The aim of all this would be to avoid falling into the «middle technology trap» or returning to the risk of «secular stagnation», where low public and private investment coupled with adverse demographic trends could lead to a situation of weak industrial activity, limited innovation and low productivity growth.

In this challenging economic and political context, the risk menu is well known to all: intensification of tariff conflicts; escalation of geopolitical risk, with a focus on the Middle East and Ukraine, affecting commodity prices; problems in the last mile of inflation, and increased financial instability. There is also a feeling that Europe and China are at a crossroads for their growth models, as the Draghi plan and the recent economic policy measures announced by the Chinese government have just highlighted. In the case of the Asian country, the economy remains highly vulnerable due to a combination of factors. Besides the problems in the real estate sector and the inertia of the country’s unfavourable demographic trends, there is excess production and a lack of confidence among the population when it comes to spending decisions, in a global context that seems unwilling to continue absorbing the country’s manufacturing surplus. In the medium term, this is likely to place China’s potential growth closer to 3%-3.5% than the official target of 5%. Meanwhile, in Europe, Germany’s weakness is an accurate reflection of the challenges facing the region, as laid out perfectly in the Draghi report: a need to boost potential growth through innovation, productivity and public and private investment, as the only way to maintain (and to pay for) the European model. This plan, with an ambitious agenda of measures for change, sounds all well and good on paper, but to achieve these goals the bloc will need to overcome hurdles such as the reticence of the usual suspects, a governance structure with clear margin for improvement and the political balance of the new European Commission.

In short, 2025 will be a year in search of a new normal, threatened by the division between economic blocs. The hope is that, as is often the case in economics, that which we cannot see is just as important as that which we can, and sooner or later the potential benefits of artificial intelligence and of all kinds of innovations that are already in the pipeline should emerge. Meanwhile, the best outcome would be to regain multilateral cooperation in order to tackle the new challenges and spread the risks together. Right now, though, that seems more of a wish than a reality.