Spain’s automotive industry: strategic and undergoing a transformation

The automotive industry is an important driver of growth and prosperity worldwide due to its contribution (i) in social terms, by facilitating people’s mobility in an efficient, safe and affordable way, and (ii) in economic terms, as a driver of innovation, a generator of good quality jobs and a pillar of international trade. In the case of Spain, it has become a mainstay of our industry and a benchmark on a global scale, thanks to a large production capacity and high productivity resulting from a skilled workforce and a great degree of plant automation. The economic crisis caused by the pandemic has taken its toll on a sector that is in the midst of a technological transformation towards electrification. A necessary transition that will be strongly supported by the Next Generation EU (NGEU) funds.

With almost 2.27 million vehicles manufactured in 2020, Spain is the second largest producer in Europe, after Germany, and the eighth largest in the world. At a European level, it is the leading manufacturer of commercial vehicles, the second for passenger cars and fourth in terms of components. If we compare the relative weight of the sector, in terms of GVA or exports, with that of the main producing countries in the euro area, Spain is at similar levels to France and Italy but far from the German giant. Far ahead are the Eastern European countries that have most recently joined the euro, such as the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary, which are more specialised in producing vehicles thanks partly to the plants of large corporate groups being located in their countries, attracted by their skilled workforce, low labour costs and a long industrial tradition (some companies in the region, such as Skoda and Tatra, date back to the end of the 19th century).

its contribution amounts to 11% of GDP if all activities related to the sector are included.

In Spain, the manufacture of motor vehicles and other transport material23 contributes 12.7% of GVA and 10.5% of manufacturing jobs, making it the second manufacturing activity after the agrifood sector (18.8% of manufacturing GVA). In addition to its direct contribution to the economy, the automotive sector also stands out for its extensive network of relationships with other activities and its knock-on effect, both economically and technologically. According to data provided by the employers’ association ANFAC (National Association of Automobile and Truck Manufacturers), referring to 2019, the share of vehicle and component manufacturing amounts to 8.5% of GDP. If, in addition, we add the activities that are complementary to manufacturing (distribution and marketing, after-sales, financial services and insurance, transportation, service stations, rental and driving schools), the figure exceeds 11% of GDP. In terms of employment, this would reach 9% of workers (1.8 million), of which 66,000 are employed by carmakers (direct employment).

From the input-output tables24 it can be seen that, beyond the intense intra-sectoral relations (37% of inputs and 18.7% of jobs begin and end in the sector itself), the sector also generates considerable demand for other sectors of activity (knock-on effect). In particular, intermediate consumption includes metal products (10.3% of the total), metallurgy (7.2%) and trade, both wholesale and retail (7.1% and 5.0%, respectively).

- 23. Data from the National Accounting System 2018. The automotive industry includes the NACE codes 29 and 30.

- 24. The input-output tables provide information both on the intermediate consumption required to manufacture each product and on the final destination of the product in question, whether it be end consumption, investment or exports.

are key to the success of a such an export-oriented sector.

The automotive sector has one of the highest rates of investment in modernisation, automation and R&D&I of all industrial sectors. Spanish production plants are among the most efficient and automated in Europe, with 1,000 industrial robots for every 10,000 employees, a figure comparable to the 1,311 robots in German plants.25 Special mention should be made of the auxiliary industry (components, machinery, materials, etc.), which is highly competitive, innovative26 and internationally renowned, manufactures a wide range of products and contributes more than 75% of the value of the vehicle. All this places the Spanish automotive industry among the most competitive in Europe: according to the KPMG index, it ranks third, behind only Germany and the United Kingdom.27

This is a strongly export-oriented sector: more than 80% of the vehicles manufactured in Spain are for export (in 2020 this figure reached 86%, very close to the record high of 2011). The propensity to export in the components segment is somewhat lower but still considerable (slightly less than 60% is exported). Exports by the automotive sector (NACE 29 and 30) totalled just over 52 billion euros in 2020, representing 19.9% of all goods exports (3.5% of GDP), far from the figures achieved at the end of the last century (28% of all goods exports) due to the greater diversification of the range of goods exported by the Spanish economy. Exports from the sector reach more than a hundred countries, although around 80% of sales go to the EU, mainly finished vehicles, while non-EU countries buy mostly components.

Only one in four of the vehicles sold in Spain has been manufactured in the country. The rest are imported from European countries such as Germany (25% of the total in 2020), France (12.3%) and the United Kingdom (6.4%), but also from Japan (7.3%) and Korea (4.4%). All in all, the balance of trade for the automotive sector is clearly favourable to the Spanish economy and, in spite of an international context marked by a slump in goods trade, the sector’s surplus grew by 21.5% in 2020 to 12.86 billion euros, 1.1% of GDP.

The sector has 17 vehicle manufacturing plants belonging to the world’s leading automotive brands (nine of them for passenger cars and SUVs, including the closure of the Nissan plant last December), along with over 1,000 equipment and component manufacturers belonging to more than 700 corporate groups. The manufacturing plants are located in 10 different autonomous regions, so the sector is well established in the industrial fabric throughout the country. In recent years, the sector has become more concentrated, with the top five brands (Seat, Volkswagen, Peugeot, Toyota and Renault) now accounting for 37% of registrations and the top ten (Kia, Hyundai, Citroën, Mercedes and Dacia), 62.6%.

In 2020, the historic pandemic crisis dealt a severe blow to the automotive sector which was one of the hardest hit initially, first by global supply chain problems and then by restrictions on non-essential businesses. However, its capacity to recover, after the total stoppage in activity and demand, was greater than in other sectors.

The crisis aggravated a situation that was already delicate due to the effects of the new environmental regulations promoted at a European level. The sector’s activity grew by a mere 0.1% in 2019 as a whole, a very slight improvement after falling by more than 1.0% in both 2017 and 2018.

The declaration of a state of emergency in mid-March 2020 brought the automotive industry to a complete standstill for about a month and a half. At the same time, the commercial network and dealerships were also closed; i.e. the capacity to meet the demand for vehicles was non-existent, with severe restrictions on movement and potential consumers confined to their homes, not to mention the uncertainty of the economic scenario in the short term. Consequently, all the indicators, for supply, demand and employment, deteriorated sharply in the first few months and then, with the easing of restrictions and consequent reopening of industry from May onwards, rebounded with some intensity, although the recovery at the end of 2020 was still incomplete.

The sector’s production plummeted 99% year-on-year in April, hitting an all-time low. The subsequent reactivation, thanks mainly to foreign demand from European markets, allowed the figures posted in 2019 to be surpassed as of September. This did not prevent Spanish factories from closing the year with a reduction of 19.6%, producing a total of 2,268,185 vehicles, half a million units fewer than those manufactured the previous year. This is the lowest level of production in seven years and is 25% below the peak in 2000, when production exceeded three million. By segment, the manufacture of passenger cars, which represent 78.8% of the total, fell by 18.9%, while that of commercial and industrial vehicles fell by 18.6%; the sharpest fall corresponds to SUVs (–76.4%), although they account for just 9,094 units. In Q1 2021, vehicle production gradually picked up but very slowly (–13.3% compared to March 2019).

The industrial production index (IPI) shows that one of the activities hardest hit in 2020 was the manufacture of motor vehicles and other transport equipment, posting the largest decline since 2009 (-18.5%), being the industry that contributed most to the overall decrease in the IPI. In terms of turnover, the trend was similar: Despite a strong recovery in the final months of the year, even reaching double-digit growth rates, the collapse in the worst months of the crisis weighed down the year’s overall balance, resulting in a cumulative decline of 10.4% in 2020. In March 2021, the sector’s turnover was still 6.2% below its March 2019 levels.

Domestic demand plummeted and has yet to recover completely. In contrast, external demand proved to be more resilient.

Domestic demand proved to be the weakest part of the sector and has not yet managed to recover from the initial impact of the pandemic. Although passenger car registrations recorded a one-off improvement in the summer months, they remained 10% to 20% below 2019 levels for the rest of the year and ended 2020 with a sharp cumulative decline, down 32.3% to 851,215, the lowest since 2013.

On the other hand, external demand showed some resistance. Although vehicle registrations also declined throughout the main European markets, they performed somewhat better than the Spanish market, with smaller falls in France (–25.5%), Germany (–19.1%), Italy (–27.9%) and the United Kingdom (–29.4%). This was key to cushioning the decline in Spanish production and was an important factor in exports gradually returning to «normal» in the second half of the year. The automotive sector is not only one of the main export sectors but also one of those that led the recovery in export sales in the last few months of the year, along with the food sector. In any case, the annual balance was negative with a fall of 15.5%, totalling 1,951,448 units exported: 1,580,297 were passenger cars (–15.4%), 8,592 SUVs (–76.7%) and 362,559 commercial and industrial vehicles (–10.6%).28

- 28. In monetary terms (customs), exports of NACE 29 and 30 categories posted positive figures as from the summer, although the year closed with a drop of 15.9%, weighed down by lower sales both of finished vehicles, fundamentally to Germany, Italy, Belgium and the United Kingdom, and of components, principally to Algeria, Germany and Portugal.

In 2020, the geographical concentration of the sector’s exports remained high: France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom were the main export destinations for Spanish vehicles, accounting for 64.1% of the total; this is undoubtedly a risk factor should these markets weaken (e.g. as a result of Brexit) or the emergence of a shock. These markets were not immune to the COVID-19 crisis, so their demand for Spanish vehicles fell, in France (–9.1%), Germany (–19.6%), the United Kingdom (–26.1%) and Italy (–9.9%). On the other hand, the Turkish market performed well, with an extraordinary increase (+101.9%) that has placed it fifth in the ranking of export destinations.

Beyond the weakening of the main European destination markets, the truth is that, in recent years, a certain slowdown in vehicle exports had already been observed. This is due to several factors, including greater international competition and the low production of hybrid and electric models, which accounted for just 7% of exports in 2020.29

- 29. The «demonisation» of diesel vehicles, which represent, in general, a very large part of the production of European manufacturers, is favouring Asian vehicles. In Spain, so far production has been slow to shift its focus towards less polluting vehicles and, moreover, such decisions need to be taken by the parent companies located in other countries.

The closure of factories, with the consequent slump in production and sales, inevitably fed through to employment. Companies were forced to resort to furloughs, an instrument that made it possible to mitigate job losses: In May, almost 60,000 workers in the sector had been furloughed, accounting for 27% of workers registered with Social Security, well above the worst figure for the economy as a whole (19.2% in April), so that effective employment (registered workers minus furloughed) was almost 28% lower than a year earlier. Since then, we have seen a gradual return of workers to their jobs, although this upward trend was interrupted during the last few months of the year, coinciding with the third wave of the pandemic and the consequent tightening of restrictive measures: Last April (latest available data), effective employment was 6% lower than in the same month of 2019.

the sector suffered extensive losses in terms of its business fabric.

Another effect of the crisis was the destruction of the business fabric, which in the automotive sector was greater than average: 409 companies30 were lost between February and December 2020 (–14.3% compared with –6.8% overall and –9.3% in the manufacturing sector), so that the year ended with a total of 2,448 companies, 14% less than a year earlier and the lowest figure in the series, which began in 2009.

The outlook for the sector in 2021 is marked by the slow recovery in activity, within an uncertain environment that encourages households to save as a precaution and companies to delay investment plans. In the short term, many potential buyers are postponing their decision to buy or are opting for second-hand models, which means the stock of vehicles continues to age (the average age has reached 13.2 years, according to data from the dealers’ association, Faconauto) and polluting emissions are not being reduced, an issue we address in the next section. Added to this is the rise in registration tax and the end of Spain’s RENOVE scrappage scheme, which complicated the recovery in 2021. All in all, a significant improvement is expected in the second half of the year, driven by the economic recovery, which will gain traction, improved consumer confidence and the new incentive scheme to promote efficient, sustainable mobility (MOVES).

- 30. Companies registered under the General Regime of Social Security. As an essential prerequisite for starting a business, entrepreneurs must apply to the General Treasury of the Social Security to register with one of its «regimes», which determines how the workers they employ will be registered with Social Security.

Globally, the automotive sector is undergoing major changes and facing important strategic challenges (combating climate change, digitalisation, changes in mobility preferences, etc.), which are forcing it to transform. Given this context, companies are becoming more concentrated while new players are emerging who see a business opportunity in electric technology. In the case of Spain, it is crucial for our automotive industry to tackle these challenges to be able to maintain its privileged position in an increasingly competitive global market, while at the same time representing an opportunity to channel the European reconstruction funds of the NGEU, as we discuss below.

One of the factors affecting the sector’s performance is the necessary adaptation to the demanding decarbonisation targets set by the EU. In 2020, the industry was already tackling the entry into force of the new European emissions regulations CAFE (Corporate Average Fuel Emissions). In 2021, the targets set will apply to 95% of all vehicles registered by each group, excluding 5% of the most polluting cars, known as phase-in. However, as from 2021 the emissions of cars sold by each manufacturer must be below 95 grams of CO2 per kilometre travelled (80 grams in 2025, 65 in 2030 and 0 in 2040). If they do not comply, marques face fines totalling millions. Therefore, the transition from the internal combustion engine to electric and connected vehicles must move forward, and major manufacturers must decide where they will locate the production of new models in the coming years.

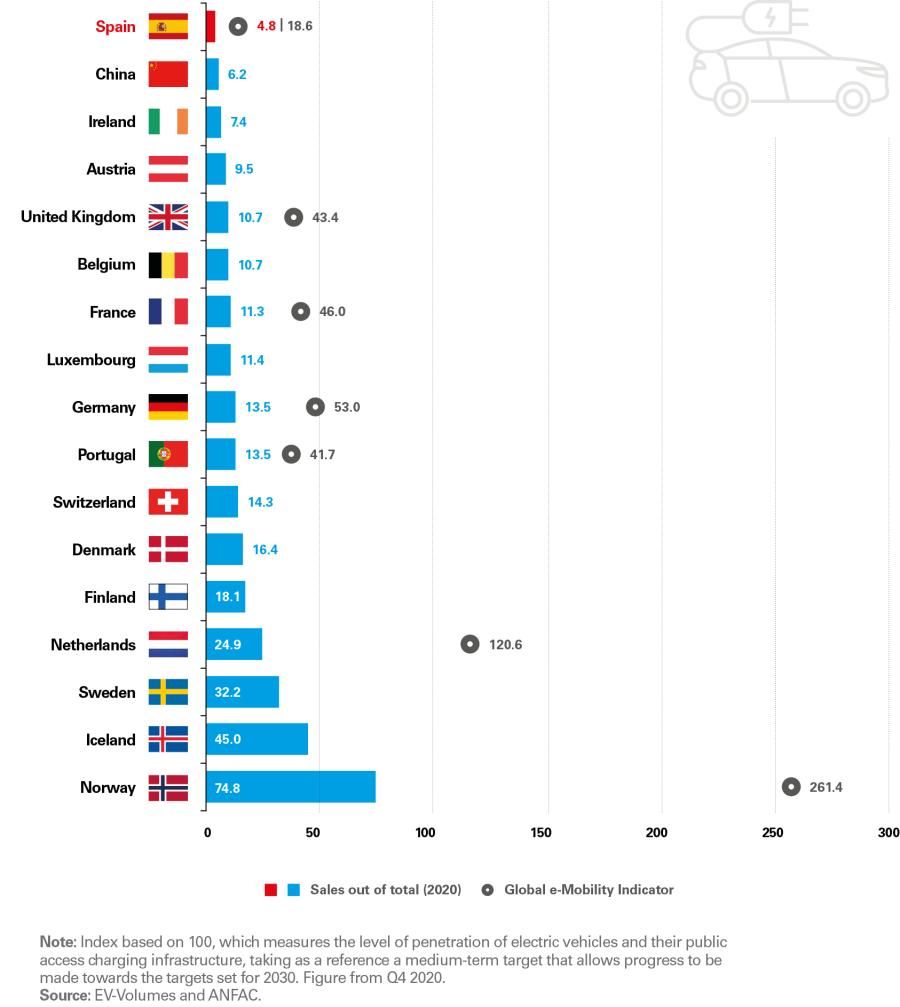

in terms of the penetration of e-vehicles and their charging infrastructure.

Although Spain’s production of e-vehicles (electric and plug-in hybrids) increased eightfold in 2020 to almost 140,000 units, their relative weight is still moderate (6.2% of the total). To fully develop electric vehicles, it is also necessary to lower the price of batteries, improve their storage capacity in order to extend vehicle autonomy and also expand the charging infrastructure (create what is called an e-mobility network). However, in terms of penetration of e-vehicles and their charging infrastructure, Spain brings up the rear in Europe. The country currently has around 8,500 charging points, making its ratio of charging points per inhabitant one of the lowest in Europe.

Electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles

The goals contained in Spain’s Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan (RTRP),31 recently submitted to the European Commission, are in line with the EU’s strategic agendas, particularly regarding the green transition, the Spain Industrial Policy 203032 and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. The RTRP includes significant advances in terms of ecological transition and digitalisation, the two areas on which the NGEU focuses. The environmental area accounts for most of the investments, highlighting those aimed at sustainable mobility (measures to advance in the decarbonisation of transport and a modal shift) and the development of electric vehicles (charging network and aid for their purchase), with more than 13.2 billion euros.

- 31. The RTRP covers 140 billion euros in transfers and loans from the NGEU funds until 2026.

- 32. This includes a digitalisation plan for four strategic sectors, including the automotive, a plan to modernise and improve the sustainability of industry, a plan to boost «green» driver industries and digitalisation and a circular economy strategy.

safe and connected mobility, including a plan to deploy a charging infrastructure and promote electric cars.

In order to streamline the management of funds, the RTRP includes a new form of public-private partnership, the so-called Strategic Projects for Economic Recovery and Transformation (PERTE). These are priority projects with a great capacity to boost economic growth, employment and competitiveness of the economy. Given the importance of the sector and the urgent need to speed up the technological transformation towards electric vehicles, the first PERTE presented was for the automotive sector: Future Fast Forward, an ambitious medium-term project (until 2030) which aims to achieve the production of a 100% Spanish connected electric vehicle.

The aim is for the project to receive the go-ahead from Brussels during the month of June, in order to start up by the end of the summer, and the first goal would be to manufacture 500,000 small electric cars in Martorell by 2025. In order for this commitment to be a success, the demand for e-vehicles must be boosted, implementation of the charging infrastructure must be speeded up and a battery plant must be set up. To meet Europe’s CO2 emission targets, there needs to be 30 million zero-emission vehicles on the road by 2030; in Spain, the production of e-vehicles would have to approach 1.5 million units.

On the other hand, last April the third edition was presented of the incentive scheme to promote efficient, sustainable mobility (MOVES), with an initial budget of 400 million euros until the end of 2023, which can be increased to at least 800 million euros. Also financed via NGEU funds, this reinforces direct aid for the purchase of electric vehicles, of up to 7,000 euros, and improves the aid provided for charging infrastructures for private individuals, home-owner communities and SMEs, as well as for fast and ultra-fast charging points. The Ministry for Ecological Transition estimates that this can contribute more than 2.9 billion euros to GDP and generate more than 40,000 jobs along the entire value chain.

Among the objectives of the recently approved Climate Change and Energy Transition Act33 is that passenger cars and light commercial vehicles should have zero direct emissions by 2050; to this end, the sale of new internal combustion vehicles, excluding those for commercial use, will be banned from 2040. In addition, in order to guarantee a sufficient charging infrastructure, among other measures it will be compulsory to install (i) from 2023, charging points at service stations with large sales volumes (power ratings equal to or greater than 150 kW in direct current [DC]) and in buildings, and (ii) from 2021, at least one charging point with a rating equal to or greater than 50 kWDC at all new fuel supply facilities.

The entire value chain within the framework of the sector’s digital transformation, with the aim of providing vehicles with increasing technology by incorporating AI and big data analysis to make production-related decisions. Recently, SERNAUTO, the association for component manufacturers, presented its Strategic Agenda 2025 which serves as a roadmap for recovery after the pandemic and industrial and technological transformation. In order to reduce the number of road deaths to zero by 2050 (Vision Zero Plan), from July 2022 the EU will require all new vehicles (cars, trucks, buses and vans) to incorporate nine advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) which, using a range of sensors and detection devices, will help to minimise the potential human errors that cause most accidents.34 Some of this equipment can also help to develop autonomous vehicles.

A change in consumer preferences must also be added to all the above. This, in a context of greater mobile connectivity and together with mobility limitations in large cities (implementation of low-emission zones aimed at reducing the emission of polluting gases into the atmosphere),35 helps to promote alternative transport models such as car sharing.36 Certainly, the extension of this alternative could cause a substitution effect (according to estimates by industry experts, a shared car could take between 3 and 15 private cars out of circulation), which would lead to a reduction in the number of private cars in the medium term. However, it is to be expected that, in the short term, the demand for cars will increase due to the urgent need to renew an ageing and polluting stock of cars.

- 33. The ultimate goal of this Act is to achieve «climate neutrality» by 2050: zero net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions/removals and a 100% renewable electricity system.

- 34. The mandatory ADAS are: intelligent speed assistance (ISA), an event data recorder (black box), drowsiness and attention warning, alcohol interlock installation facilitation, emergency stop signal, reversing detection, tyre pressure monitors and lane keeping assist and advanced emergency braking systems (the last two for passenger cars and vans only). According to Spain’s Directorate-General for Traffic (DGT), the use of these systems reduces the risk of accident by 57%. Brussels estimates this will prevent 25,000 deaths and 140,000 serious injuries over the next 15 years.

- 35. The RTRP includes the introduction of Low Emission Zones (LEZs), which the Climate Change Act already makes mandatory in cities with more than 50,000 inhabitants and cities with more than 20,000 inhabitants when they have pollution problems.

- 36. This is an alternative to a privately owned individual car, allowing access to a fleet of vehicles located in the vicinity of the person’s home and paid according to the length of time and kilometres the vehicle is driven.

- 23. Data from the National Accounting System 2018. The automotive industry includes the NACE codes 29 and 30.

- 24. The input-output tables provide information both on the intermediate consumption required to manufacture each product and on the final destination of the product in question, whether it be end consumption, investment or exports.

- 25. Data for Spain from ICEX (2019) and data for Germany from the International Federation of Robotics (2019).

- 26. It allocates more than 4% of its turnover to innovative activities, well above the national average (1.1%).

- 27. Agenda Sectorial de la Industria de Automoción, 2017.

- 28. In monetary terms (customs), exports of NACE 29 and 30 categories posted positive figures as from the summer, although the year closed with a drop of 15.9%, weighed down by lower sales both of finished vehicles, fundamentally to Germany, Italy, Belgium and the United Kingdom, and of components, principally to Algeria, Germany and Portugal.

- 29. The «demonisation» of diesel vehicles, which represent, in general, a very large part of the production of European manufacturers, is favouring Asian vehicles. In Spain, so far production has been slow to shift its focus towards less polluting vehicles and, moreover, such decisions need to be taken by the parent companies located in other countries.

- 30. Companies registered under the General Regime of Social Security. As an essential prerequisite for starting a business, entrepreneurs must apply to the General Treasury of the Social Security to register with one of its «regimes», which determines how the workers they employ will be registered with Social Security.

- 31. The RTRP covers 140 billion euros in transfers and loans from the NGEU funds until 2026.

- 32. This includes a digitalisation plan for four strategic sectors, including the automotive, a plan to modernise and improve the sustainability of industry, a plan to boost «green» driver industries and digitalisation and a circular economy strategy.

- 33. The ultimate goal of this Act is to achieve «climate neutrality» by 2050: zero net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions/removals and a 100% renewable electricity system.

- 34. The mandatory ADAS are: intelligent speed assistance (ISA), an event data recorder (black box), drowsiness and attention warning, alcohol interlock installation facilitation, emergency stop signal, reversing detection, tyre pressure monitors and lane keeping assist and advanced emergency braking systems (the last two for passenger cars and vans only). According to Spain’s Directorate-General for Traffic (DGT), the use of these systems reduces the risk of accident by 57%. Brussels estimates this will prevent 25,000 deaths and 140,000 serious injuries over the next 15 years.

- 35. The RTRP includes the introduction of Low Emission Zones (LEZs), which the Climate Change Act already makes mandatory in cities with more than 50,000 inhabitants and cities with more than 20,000 inhabitants when they have pollution problems.

- 36. This is an alternative to a privately owned individual car, allowing access to a fleet of vehicles located in the vicinity of the person’s home and paid according to the length of time and kilometres the vehicle is driven.