Ukraine’s reconstruction and its potential energy implications for Europe

One of the most highly debated issues around a partial or total peace agreement and the process of Ukraine’s reconstruction is what will happen to the European energy scenario. Will Europe once again be a major customer of Russian energy?

Since Donald Trump’s arrival in the White House, attempts have been made to bring Russia and Ukraine to the negotiating table. On 25 March, a first step was taken with the signing of a partial ceasefire deal between Ukraine and Russia, with the aim of guaranteeing the safety of navigation and trade in the Black Sea. In addition, it included a commitment not to carry out attacks against energy infrastructure, highlighting the sector’s importance for both domestic needs and fossil fuel export revenues in these two countries. Beyond the political and social considerations, a lasting peace agreement would have a positive impact on international energy flows and would favour an easing of prices, especially in the case of gas. The EU, aware of this advantage and of the need to restore the energy facilities damaged during the war, has begun planning the rebuilding of Ukraine’s energy infrastructure and other sectors vital for economic growth.

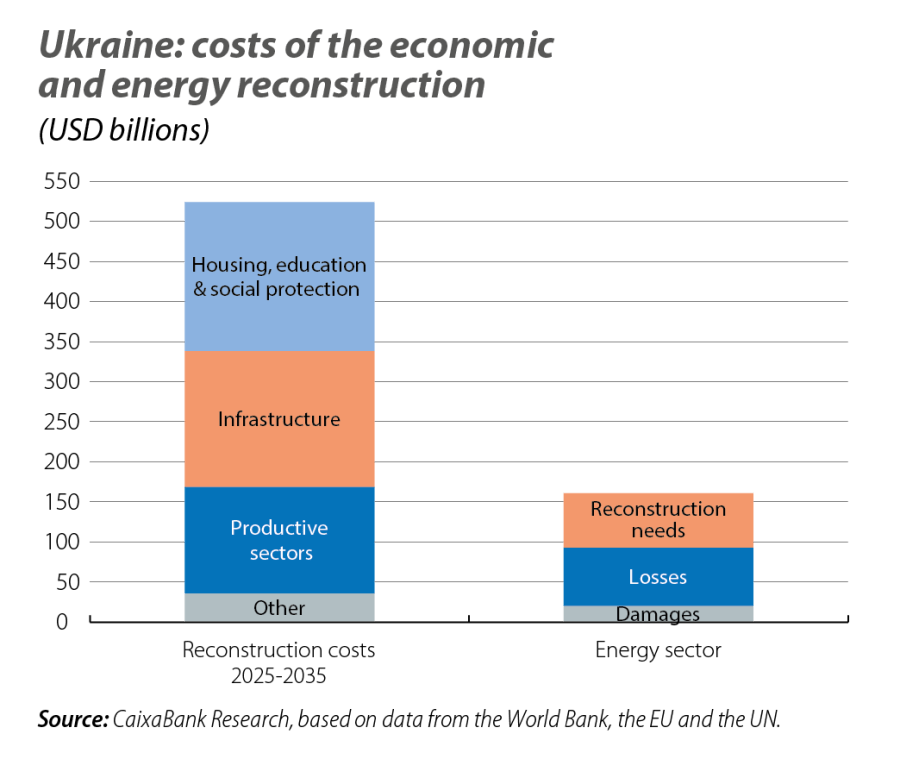

Together, the World Bank, the EU and the United Nations1 have estimated that the value of direct damage from the war in Ukraine, between February 2022 and December 2024, amounts to 176 billion dollars (170 billion euros), which is 15.8% higher than the figure calculated at the end of 2023. Over the past year, there has been a widespread increase in damage across the residential, transportation, trade and industrial sectors. However, losses in the energy sector rose by 70% as a result of damage to assets related to electricity generation and transmission, energy distribution infrastructure and urban heating (see first chart).

- 1. See «Fourth Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment (RDNA4)». World Bank Document, February 2025.

These three international organisations estimate that the cost of Ukraine’s reconstruction and recovery needs in both the public and private sectors over the next decade amount to 524 billion dollars (506 billion euros), approximately 2.8 times Ukraine’s estimated nominal GDP in 2024. Housing (16%) would top the aid priority list, followed by transportation (15%), energy (12%), trade and industry (12%) and agriculture (11%).

At the same time, and in order to obtain the necessary support for Ukraine's future accession to the EU, the Ukrainian government has launched a programme of reforms and investments set out in the Ukraine Plan.2 Ukraine is taking steps to attract private investment into the energy sector and legislative and structural reforms (focusing on improving energy security and the transition to renewable energy) have been accelerated in order to align the sector with EU regulations and standards, as an essential requirement in order to compete in European markets.

- 2. In May 2024, the Ukrainian government adopted the EU’s Ukraine Plan. This is a comprehensive reform and investment programme for the period 2024-2027, covering most sectors of the Ukrainian economy.

One of the most highly debated issues around a partial or total peace agreement and the reconstruction process is what will happen to the European energy scenario. Questions remain over whether Europe will resume significant imports of Russian energy or what impact Russia’s return to the European scene will have on oil and gas prices remain central to the unresolved questions.

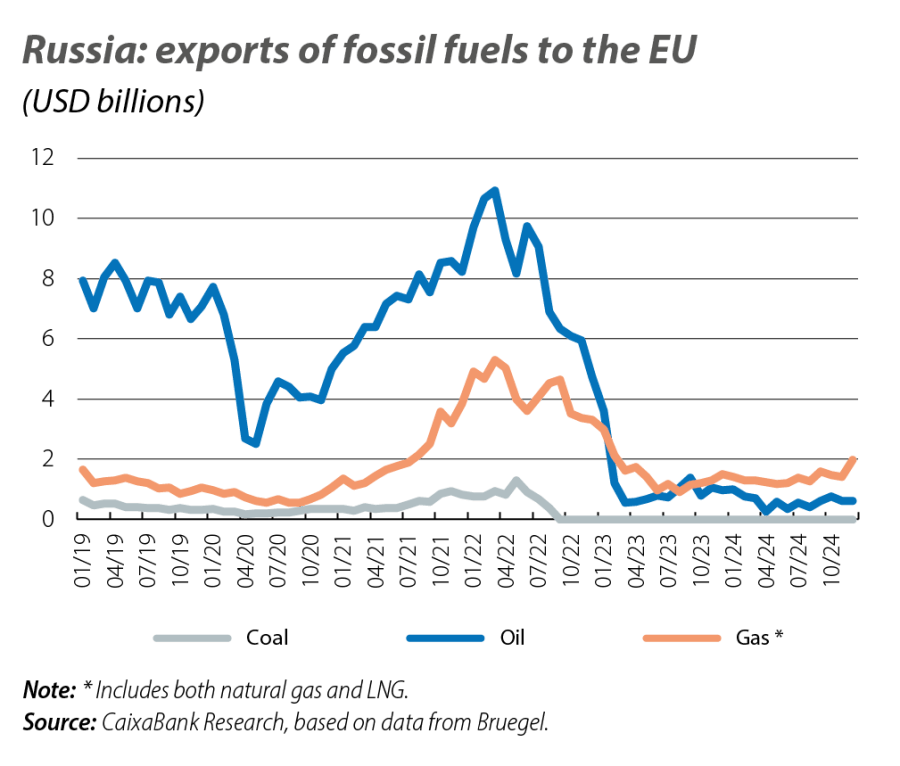

With regards to oil, following the invasion of Ukraine, the West sanctioned Russian crude oil exports,3 although this did not prevent Russia from maintaining a high production rate. Since then, flows from Russia to Europe have been effectively minimised (see second chart), and Russian oil shipments have been redirected to China, India and Turkey. Europe, for its part, has made up for this shortfall by buying barrels from the Middle East and the US. In a potential peace agreement, there is a possibility that the US might ease sanctions related to the price cap imposed by the G7, in which case the discount premium at which the Urals barrel is currently being traded would be diluted, causing it to lose its competitive advantage over the Brent barrel price for Asian buyers. This is unlikely to significantly affect Europe’s oil import volumes and prices could register downward pressures related to the increase in OPEC’s supply beginning in April.

- 3. In 2022, the US and the UK banned imports of oil and derivative products from Russia. The EU also banned them beginning in late 2022 and, in 2023, restricted the provision of associated services (shipping and maritime insurance) for importers of Russian oil. In parallel, in 2022, the G7 imposed a cap on the sale price of a barrel of Russian oil transported by sea at 60 dollars. This cap does not affect the crude oil that arrives in Europe via pipelines to countries without access to the sea.

In the case of gas, in contrast, a peace agreement could have bigger implications for Europe. The current European gas scenario is very different to before the outbreak of the war. On the one hand, the demand for natural gas in Europe fell by 20% between 2021 and 2024. The increase in the gas price in Europe since the start of the war, the deployment of renewable energies and the energy-saving policies promoted by the EU4 have led to a considerable drop in demand. On the other hand, Europe has sought alternative suppliers of natural gas and has placed greater emphasis on liquefied natural gas (LNG), mainly from the US, as well as on the entire storage and regasification industry associated with this fuel. Although Russian gas exports to Europe have plummeted, it is worth noting that since 2022, Russia has continued to sell LNG to Europe, accounting for 18% of the total LNG imported by Europe (excluding Turkey) in 2024.

Another factor that has changed dramatically is the routes used to import gas from Russia to Europe via pipeline. Of the four access routes that existed at the start of the war (the Yamal pipeline through Poland, Nord Stream through Germany, Brotherhood through Ukraine and Turk Stream through Turkey), only the Turkish gas pipeline is currently operational. Unlike oil, the EU has not explicitly sanctioned natural gas flows via pipeline, and the interruptions in supply have been due to legal, political and logistical issues.

However, when peace comes, it seems unlikely that the volume of Russian gas exports to Europe will return to pre-war levels. In the last three years, EU countries have inverted their preference for cheap energy in favour of energy security. Most Member States are opposed to the return of Russian gas to Europe, with the exception of Slovakia and Hungary, so they will support the diversification of suppliers and will not make significant investments in reinstating the disused pipelines. In addition, the war has accelerated a series of structural changes in the EU with a longer-term profile, such as investment in renewable energy sources, the relocation of some gas-intensive industries and the development of LNG capacity, all of which diminish the potential growth of demand for Russian gas.

All in all, in the event of a balanced peace agreement between Russia and Ukraine, the return of Russian oil and gas flows to Europe is unlikely to reach pre-war levels. In addition to the political, legal and security issues, the significant damage suffered by Ukraine’s energy infrastructure during the conflict, despite being a priority objective for the reconstruction, will slow down the normalisation of these flows.

- 4. See «REPowerEU: energy policy in EU countries’ recovery and resilience plans», which aims to end dependence on Russian fossil fuels by 2027, saving energy and diversifying supplies. And «Fit for 55», the EU package of measures on European climate legislation with the goal of cutting EU greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030.

- 1. See «Fourth Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment (RDNA4)». World Bank Document, February 2025.

- 2. In May 2024, the Ukrainian government adopted the EU’s Ukraine Plan. This is a comprehensive reform and investment programme for the period 2024-2027, covering most sectors of the Ukrainian economy.

- 3. In 2022, the US and the UK banned imports of oil and derivative products from Russia. The EU also banned them beginning in late 2022 and, in 2023, restricted the provision of associated services (shipping and maritime insurance) for importers of Russian oil. In parallel, in 2022, the G7 imposed a cap on the sale price of a barrel of Russian oil transported by sea at 60 dollars. This cap does not affect the crude oil that arrives in Europe via pipelines to countries without access to the sea.

- 4. See «REPowerEU: energy policy in EU countries’ recovery and resilience plans», which aims to end dependence on Russian fossil fuels by 2027, saving energy and diversifying supplies. And «Fit for 55», the EU package of measures on European climate legislation with the goal of cutting EU greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030.