The new EU economic governance framework

In this article we analyse what we can expect of European public accounts in the coming years, following the entry into force of the European Union’s new economic governance framework.

On 30 April 2024, the new EU economic governance framework,1 which is based on the proposals made by the Commission in 2023, came into force.2 The new fiscal rules maintain the 3% public deficit and the 60% public debt benchmark thresholds. However, they seek to simplify the budgetary rules by providing guidance on a single defined fiscal indicator on net primary expenditure (see the Technical Appendix) and to give Member States greater flexibility through the preparation of medium-term plans, which become the cornerstone of the new economic governance framework. What can we expect from European public accounts in the coming years?

Green light from the Commission to the first fiscal plans under the new rulesreglas

On 21 June 2024, the Commission provided Member States with preliminary guidance for the preparation of their medium-term structural budgetary plans, including the framework for medium-term debt projections and the main budgetary, macroeconomic and financial assumptions.3 On the basis of this information, the Commission sent to the 16 countries with debt and/or deficits above the thresholds4 a multi-year reference path for net primary expenditure, as well as the associated path for the primary structural balance, while for the rest of the Member States it included technical information with the minimum value required for the primary structural balance at the end of the plan. In both cases, the information submitted included a scenario with a four-year adjustment period, as well as an alternative scenario with a three-year extension.

Following this preliminary guidance, the Commission and the national authorities held technical dialogues prior to the preparation of the plans, which, in accordance with the regulation, were required to be sent no later than 20 September 2024. Among other elements, these plans should contain the following information:5 (i) the multi-year path of net expenditure and the justification for any upward deviation relative to that sent by the Commission, (ii) the underlying macroeconomic and budgetary assumptions and the justification for any deviations from the projections framework, (iii) the planned fiscal-structural measures, (iv) details on the consistency with the Council’s country-specific recommendations and with the EU’s common priorities, as well as on the compatibility with the Recovery and Resilience Plan and other European funds, and (v) where appropriate, the commitments and the impact of reforms and investments supporting an extension of the adjustment period by three years.

On 26 November 2024, the Commission published the so-called Autumn Package of the 2025 European Semester, in which it included a status update on the new economic governance framework.6 Of the 27 Member States, five had not submitted their medium-term structural budgetary plans due to the holding of elections or the formation of new governments, including three countries with debt and/or deficits above the thresholds (Germany, Belgium and Austria). Of those that had sent the plans, the Commission has recommended to the Council the adoption of those of 20 Member States, while it continued to evaluate the plans submitted by Hungary and recommended that the Netherlands submit a revised plan aligned with the technical information received.7 Five of the countries with debt and/or deficits above the thresholds have requested a three-year extension of the adjustment period (Italy, France, Spain, Romania and Finland). Finally, of the 17 euro area countries that are required each year to send their draft budgets for the following year, three had not done so (Spain, Belgium and Austria), while nine of them were not fully or were partially aligned with the fiscal recommendations and the implementation of the medium-term plans.

The next step is the Council’s scrutiny of the Commission’s recommendations,8 with particular attention being paid to Member States with debt and/or deficits above the thresholds that have included in their plans an average annual increase in their primary expenditure in excess the guidance received.9 Attention will also be paid to the relevance of the reforms and investments set out by the countries requesting an extension of the adjustment period. In the event of any discrepancies, the Council will recommend the revision of the medium-term plans sent or the setting of an expenditure path in line with the guidance received from the Commission. Subsequently, in advance of the spring package of the 2025 European Semester, member countries will need to submit the first annual report on their progress in the implementation of the medium-term plans.

- 3Set out in the Commission’s 2024 spring forecast: European Economic Forecast. Spring 2024.

- 4Germany, Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Poland, Portugal and Romania.

- 5On 21 June 2024, a guide was published on how to present the information in the plans: Notice – Guidance to Member States on the Information Requirements for the Medium-Term Fiscal-Structural Plans and for the Annual Progress Reports.

- 6«Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Central Bank 2025 European Semester: bringing the new economic governance framework to life».

- 7Only two countries (Denmark and Malta) submitted their plans within the 20 September 2024 deadline. From the date of receipt, the Commission has six weeks to assess the plans (with the possibility to extend this period by an additional two weeks). In the case of Hungary, the plan was submitted on 4 November.

- 8The regulation specifies a period of six weeks from the Commission’s recommendation.

- 9See Table 2 of Appendix II in «Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Central Bank 2025 European Semester: bringing the new economic governance framework to life».

What fiscal adjustment is included in the medium-term plans? Outlook and risks

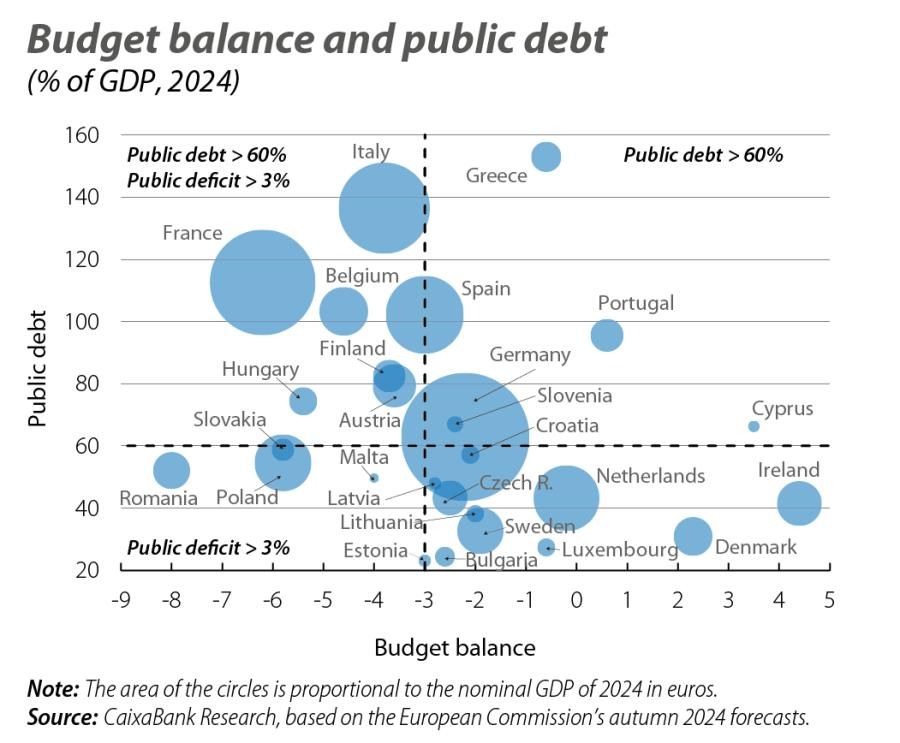

The state of public finances in the EU is compromised in the wake of the string of shocks since the Great Financial Crisis of 2009, the euro area sovereign debt crisis which lasted until 2012, the pandemic of 2020 and the invasion of Ukraine and the energy crisis since 2022. The first chart shows how the vast majority of EU Member States have debt and/or deficits above the thresholds, including systemic economies such as Italy, France and Spain, which have very high levels of public debt (above the 90% threshold defined by the Commission).

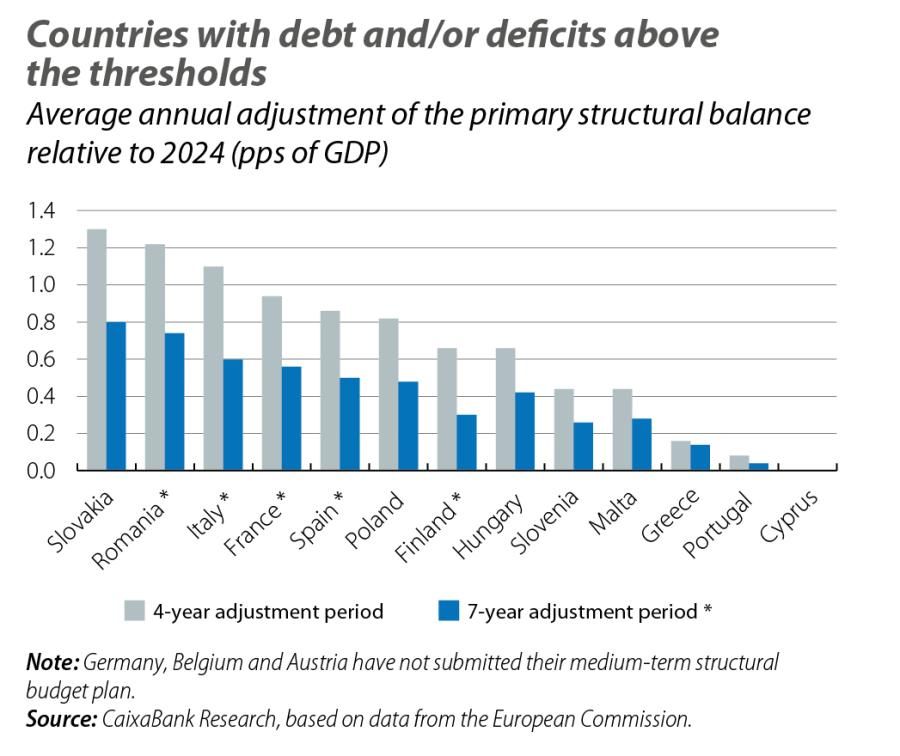

Correcting these fiscal imbalances is undoubtedly one of the EU’s major economic policy challenges, as reflected in the consolidation efforts included in the medium-term plans. To illustrate this, given the interpretative difficulties regarding the trajectory of the new fiscal benchmark, we prefer to provide a summary of the expected paths in the primary structural balance. To this end, we take the figures provided by the Commission on 21 June 2024 as guidance. Unlike the plans sent by each Member State, this guidance offers the benefit of using a more uniform methodology for estimating potential GDP.

In the absence of data for Germany, Belgium and Austria, the second chart shows the average annual adjustment indicated by the Commission relative to the values estimated for 2024 under both the scenario with a four-year adjustment period and with the three-year extension. Among the countries that have not requested an extension of the adjustment period, of particular note are the annual adjustments proposed by Slovakia (1.3 pps per year), Poland (0.8 pps) and Hungary (0.7 pps), while those proposed by Slovenia and Malta are more moderate and those of Greece, Portugal and Cyprus are low. Among the countries that have applied for a three-year extension, the biggest adjustment is that proposed by Romania (0.7 pps per year), followed by those of Italy and France (both 0.6 pps), Spain (0.5 pps) and Finland (0.3 pps). Weighting the data according to the nominal GDP of the available countries, and taking into consideration the different adjustment periods, the expected annual increase in the primary structural balance will be around 0.6 pps over the next four years. The consolidation effort this will entail for these countries is considerable.

Complying with the planned adjustments will not come without its challenges, including the domestic political difficulties in approving the budgets that accompany the implementation of the medium-term plans. A case in point is France, where the lack of parliamentary support has led to a no confidence vote and the breakdown of the government. The complex geopolitical context also raises doubts related to the growing spending needs that are required to cover the EU’s common priorities, particularly those linked to strategic autonomy and security and defence policy, as well as to financing the competitive leap set out in the Draghi report.10 Recalling lessons from the past, with low potential growth as a starting point and with the gradual fading of the boost provided by the NGEU funds, governments will have to tread very carefully to ensure that the contractionary effect of the proposed fiscal adjustments does not end up tainting the initial goal of reducing public debt. Moreover, all this is in a context in which the financial markets have already seen – moderately for now – new episodes of differentiation between Member States’ government securities.

- 10See the Focus «Draghi proposes a European industrial policy as a driving force to address the challenges of the coming decades» in the MR10/2024.

Technical appendix

The new fiscal rules define a single indicator for net primary expenditure,1 on which the Commission sends a multi-year reference path to Member States with debt and/or deficits above the thresholds, while it sends technical information to all other countries. This is the starting point from which national governments then develop a medium-term structural budgetary plan with adjustment measures covering a four-year period.2The option exists to extend this adjustment period by an additional three years if they incorporate reforms and investments to boost economic growth and support the EU’s common priorities.3

The reference path for the net primary expenditure indicator is determined by the need to ensure that the debt follows a clearly downward trajectory after the adjustment period or that it remains at prudent levels, even in adverse scenarios. In addition, it should also ensure that the deficit is reduced and remains below 3% of GDP, considering the costs associated with the ageing of the population that will materialise after the adjustment period. Operationally, this translates into the need to comply with a number of requirements.

On the public debt side, the first requirement is that the GDP ratio must decrease continuously in the 10 years following the adjustment period in the baseline scenario for growth, inflation and interest rates, as well as in three risk scenarios defined by the Commission. These risk scenarios consider, respectively, a higher cost of financing, a lower primary structural balance and a less favourable differential between growth and financing costs.4 The second criterion for public debt is that, in an environment of uncertainty regarding the baseline scenario, after five years the ratio to GDP must be equal to or less than the value at the end of the adjustment period with a probability of at least 70%. Finally, the annual rate of reduction of the GDP ratio should be at least 0.5 pps if it is between 60% and 90% and 1 pp if it is greater than 90%.

On the public deficit side, the first criterion, which was already in place under the previous governance framework, is an annual adjustment of at least 0.5 pps per year if the deficit exceeds 3% of GDP.5 The second requirement applies to countries with a structural deficit above 1.5% of GDP and establishes an annual adjustment of the primary structural balance of 0.4 pps for these countries if the adjustment period is four years, or of 0.25 pps where the three-year extension is applied.

In short, the new fiscal rules define a single benchmark in terms of net primary expenditure, which effectively helps to simply the budgetary orientation of Member States, while maintaining the necessary analytical rigour in order to assess the sustainability of public debt. However, the revision of the rules also entails some difficulties. The main one is that the economic policy readings on the path of net primary expenditure are not immediate and it is difficult to interpret the magnitude of the fiscal adjustments required, as well as their impact on economic growth.

Some aspects of the methodology also have room for improvement, such as the criteria for defining risk scenarios, which are somewhat arbitrary both in terms of the magnitude of the stress applied (the same for all countries, including for the deviations in the primary structural balance regardless of the adjustment to be made) and in terms of when they take place (at the end of the adjustment period) and their duration (some are temporary, such as the rise in interest rates, while others are permanent).

- 1Defined by the regulation as public spending after deducting: (i) interest payments, (ii) discretionary revenue measures, (iii) expenditure linked to EU programmes that are fully funded by revenue from EU funds, (iv) national expenditure for the co-financing of EU-funded programmes, (v) cyclical elements of unemployment benefit expenditure and (vi) expenditure and revenue measures associated with one-off or temporary events.

- 2Four or five years, depending on the length of the legislative period in each Member State.

- 3These include the green and digital transition, energy security, strategic autonomy, security and defence strategy, demographic challenges, employment targets, and socio-economic resilience and convergence.

- 4See the «Debt Sustainability Monitor 2023».

- 5The adjustment relates to the primary structural balance between 2025 and 2027, and to the total structural balance from 2028 onwards.