The European Green Deal, between the desirable and the feasible

The EU is leading the way in the reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, but there is still a long way to go both on the Old Continent and in the rest of the world if we are to avoid an increase in temperature above 2°C. With the aim of consolidating this leadership, the European Commission (EC) has presented the Green Deal, a framework (or growth strategy in the words of the EC) that includes measures aimed at achieving a level of net zero emissions, boosting economic growth with a more sustainable use of natural resources and doing so in a way that is fair within countries, sectors and individuals. To this end, one of the first steps taken by the EU has been to incorporate regulation that forces itself to reduce GHG emissions by 50% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels (instead of the 40% set out in the Paris Agreement) and to be a climate neutral before 2050.1 Despite the goodness of these intentions, are these objectives plausible? Are the measures taken by the EU sufficient? How are these plans altered by COVID-19?

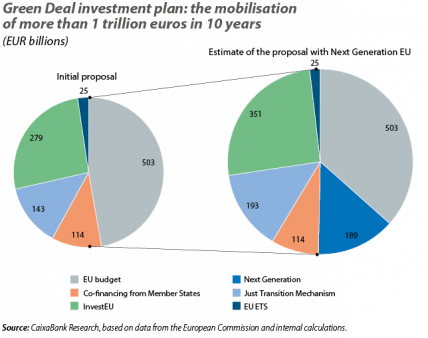

The Green Deal has been presented by the EC of Ursula Von der Leyen as the flagship of its mandate, which is reasonable in view of the concerns about the climate emergency in Europe. According to a survey by the European Investment Bank (EIB),2 82% of European citizens believe that the climate emergency is having an impact on their lives (this perception is more widespread among the Mediterranean states than those of Northern Europe). Also, 47% of Europeans see the climate emergency as one of the greatest threats their country faces. In this context, the EC has presented the Green Deal investment plan, with which it intends to «mobilise» at least 1 trillion euros over the next 10 years.3 However, it is necessary to break down this figure and understand what exactly is meant by the term «mobilise».

An initial investment proposal that raised doubts

In its initial proposal, presented in January 2020, half of this mobilisation would come from the EU’s own resources. At present, 20% of the 2014-2020 budget is considered to be green and, under the Green Deal, the EC intends to increase this to 25% for the period 2021-2027.4 To this end, among other measures, it proposes allocating 40% and 30% of the budgets of the Common Agricultural Policy and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund, respectively, to tackling the climate emergency. In this regard, the EU’s new taxonomy will help ensure that this 25% of the budget is truly green, as it specifies the requirements for an investment or asset to be considered as such.5 In addition, the EC estimates that Member States will co-finance some of the green projects included in the EU budget with 114 billion euros. On the other hand, the EU will deploy the Just Transition Mechanism, to which it initially wanted to contribute 7.5 billion euros and through which more than 143 billion euros would be mobilised over a 10-year period to help the regions hardest hit by the transition (for example, those with a high share of employment in the fossil fuel extraction and production sector or in energy-intensive industries).6

The second largest contribution to the Green Deal investment plan consists of 279 billion euros from private investments made through the EIB’s InvestEU programme, the successor to the so-called Juncker Plan. This programme would work very much like the Juncker Plan: the EIB would provide guarantees to projects that contribute to combating the climate emergency, thereby encouraging private investment in this field.7

Finally, the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) will also contribute to the trillion-euro investment with 25 billion euros collected through the auctioning of carbon credits.8 Moreover, the EC proposes creating a carbon border tax to prevent companies from relocating their production centres to regions with less stringent environmental regulations (known as carbon leakage).

Thus, of the 1 trillion euros initially announced by the EC, the real increase in EU spending on the fight against the climate emergency would only amount to a 5-pp increase of the EU budget (from 20% to 25%) being allocated for this purpose, plus 7.5 billion euros within the Just Transition Fund. The rest will come from the «mobilisation» of private and public investment, an expression that the institution uses to refer to investments, mostly private, that materialise thanks to the guarantees offered by the EU. However, most groups in the European Parliament have asked that this expression be no longer used in order to preserve the EU’s credibility.9

The Green Deal as a cornerstone of the European Commission’s Recovery Plan

At the end of May, the EC proposed a 750 billion-euro programme for its recovery plan (Next Generation EU) aimed at supporting the region’s economic recovery following the COVID-19 epidemic, taking into account the EU’s long-term challenges (primarily decarbonisation and digitalisation). This programme would be financed through the issuance of EU debt. Following the same scheme as the budget for 2021-2027, around 25% of this amount will go towards measures for adapting to and mitigating the climate emergency. Among the new measures, the contribution to the Just Transition Fund would increase from 7.5 billion euros to 40 billion euros and the EC would contribute 15.3 billion euros to the InvestEU fund in order to mobilise up to 240 billion euros (approximately 30% of which would go to green projects).

Also, a significant portion of this new sum will be invested in the renovation of buildings to make them more energy-efficient. Thus, while supporting the labour-intensive construction sector and reducing unemployment, emissions from that sector will also be reduced – an important step given how much room for improvement it has in terms of energy efficiency. It should be recalled that buildings account for 36% of total EU emissions and the EC estimates that, in order to become the first climate-neutral continent, Europe’s buildings will need to be renovated at twice the current rate (between 0.8% and 2.4% per year, depending on the Member State).

An investment that appears to fall short

Thus, taking into account the initial proposal and the Next Generation EU proposal, the total mobilisation of funds aimed at galvanising a greener economy would amount to approximately 1.37 trillion euros over 10 years, which corresponds to an annual investment of 137 billion euros (1% of EU-27 GDP in 2019). This is in comparison to the EC’s own estimate that, in order to achieve the aforementioned objective of the Paris Agreement (i.e. a 40% reduction in GHG emissions), an annual investment of 240 billion euros would be required.10 If we take into account the proposed new target (a 50% reduction in emissions instead of 40%) and we assume a similar relationship in the investment required to reduce each unit of GHG emissions, then we reach the conclusion that the annual investment requirements increase to approximately 300 billion euros. Thus, the Green Deal Investment Plan would represent 45% of the necessary investment, meaning that the private sector and Member States would still need to be more ambitious.

Far from being an obstacle, the COVID-19 epidemic could act as a catalyst for the green transition

The humanitarian, economic and social cost of the health crisis triggered by COVID-19 will undoubtedly be extremely high, and the efforts of the authorities must focus on minimising the cost in lives, mitigating the economic impact of the lockdown and supporting the recovery of economic activity. On this last point, the measures taken to date could accelerate some of the trends that had already been taking place at the productive and institutional level which will contribute to curbing climate change:

• In February, the EC launched an appraisal of the EU’s fiscal framework with the intention of adapting it to the challenges that have been laid down (the Green Deal, digital transformation, reducing inequality, etc.)11 and, following the outbreak of the health crisis, some of the issues raised at that time have been accelerated. For instance, the EU will issue its own debt – something it had already done on certain previous occasions – to finance the Next Generation EU proposal. In addition, it is once again looking at the possibility of collecting some taxes directly (such as a digital tax or green taxes). If these proposals were to be implemented and become the norm, they would give the institution greater decision-making autonomy and greater funding capacity. This, in turn, would allow it to be more ambitious in its policies to address challenges, such as climate change, that go beyond the scope of the Member States themselves.

• The COVID-19 epidemic has shown that remote working is a valid system for many businesses and occupations and that it has benefits both in terms of achieving a better work-life balance and in tackling the climate emergency. As explained in another article of this same report,12 in Spain around 30% of people in employment can work from home, a percentage that increases in urban areas up to 40%. Thus, if remote working were implemented in Spain two days a week for these workers, annual GHG emissions from land transportation would be reduced by 3%13 – a small step, but a step nonetheless.

In short, it is only fair to acknowledge that the EC has made a firm commitment to combating climate change. However, it lacks the necessary strength to achieve this goal by itself, so the action of states and private initiatives will be key if we are to avoid global warming in excess of 2°C. Taking advantage of a turning point like the current one could be vital in tipping the balance, in the medium and long term, towards a sustainable and environmentally friendly economy.

Ricard Murillo Gili

1. By climate neutral, we mean that GHG emitted into the atmosphere are captured by natural carbon sinks or using carbon removal technologies, which have not yet been implemented. The slower the reduction in emissions, the more important the deployment of these technologies will be, as there will be more GHG in the atmosphere increasing the temperature of the planet.

2. Second European Investment Bank climate survey.

3. This was the proposal prior to the economic recovery programme presented on 27 May.

4. The EU budget for 2021-2027 is currently being negotiated, and the health crisis triggered by the COVID-19 outbreak could significantly change its size and the amounts earmarked for the climate emergency.

5. For more details, see the article «The necessary move towards a green financial sector» in this same Dossier.

6. For more details on the Just Transition Mechanism, see the article «The EU’s climate transition: a question of justice» in this same Dossier.

7. In this regard, albeit outside the framework of the Green Deal, the EIB aims to make 50% of the financing it offers in 2025 green, compared to the current level of 25%.

8. For further details on how the EU ETS works, see the article «How to act in the face of climate change? Actions and policies to mitigate it» in the Dossier of the MR11/2019.

9. In the resolution proposed on 12 May 2020, the EC was alerted to «the use of financial wizardry and dubious multipliers» to announce ambitious figures.

10. This figure increases by 100 billion euros and 130 billion euros when taking into account, respectively, the additional investment required to develop a green transport infrastructure and to meet other environmental objectives besides global warming. See European Commission (2020). «Identifying Europe’s recovery need».

11. See the Focus «A step towards a reform of the fiscal rules in Europe?» in the MR03/2020.

12. See the Focus «The COVID-19 outbreak provides a boost to remote working» in this same Monthly Report.

13. To calculate this figure, we have taken mobility data from the Enquesta de mobilitat en dia feiner (Working-day mobility survey) conducted by Barcelona’s metropolitan transport authority, ATM, as well as emission data from the Oficina Catalana del Canvi Climàtic (Catalan Office for Climate Change) and other data from the Labour Force Survey.