Challenges and outlook for Portugal’s public debt:reflections on the withdrawal of the ECB

The risk premium on Portuguese debt has fallen significantly in the last 18 months and has remained well below those of Italy and Spain. What explains this dynamic?

Firstly, it is important to look at the macroeconomic context. Portugal’s economy has enjoyed a rapid post-pandemic rebound, with GDP growth of around 6% since the end of 2019, well above the euro area average of 3% and that of the region’s main economies. For example, Germany’s growth has been just 0.1% higher.

Secondly, the government has shown a firm commitment to consolidating the public accounts, and this has enabled positive primary balances to be achieved in recent years (except during the pandemic). In 2023, Portugal once again recorded a fiscal surplus and all the indicators suggest that it will remain positive in the coming years. This is a commitment shared by the main political parties, which helps to consolidate this expectation. The country’s significant economic growth and fiscal consolidation1 has allowed the public debt ratio to remain below 100% of GDP in 2023, something that has not happened since 2009. This consolidation of the public finances in the post-pandemic period stands in contrast to what has been observed in other euro area countries: the decline in Portugal’s public debt ratio (by 4.2 pps in 2022 compared to 2019)2 is the fourth biggest reduction in the euro area, while the bloc as a whole has seen its ratio increase (by almost 7 pps in the same period).

The consolidation of the public accounts (in addition to other important factors, such as the significant growth of the economy, the reduction of private debt and the strength of the banking sector) has been decisive in the assessment of country risk. Portugal’s public debt has an A-grade risk level according to the assessment of all the rating agencies.

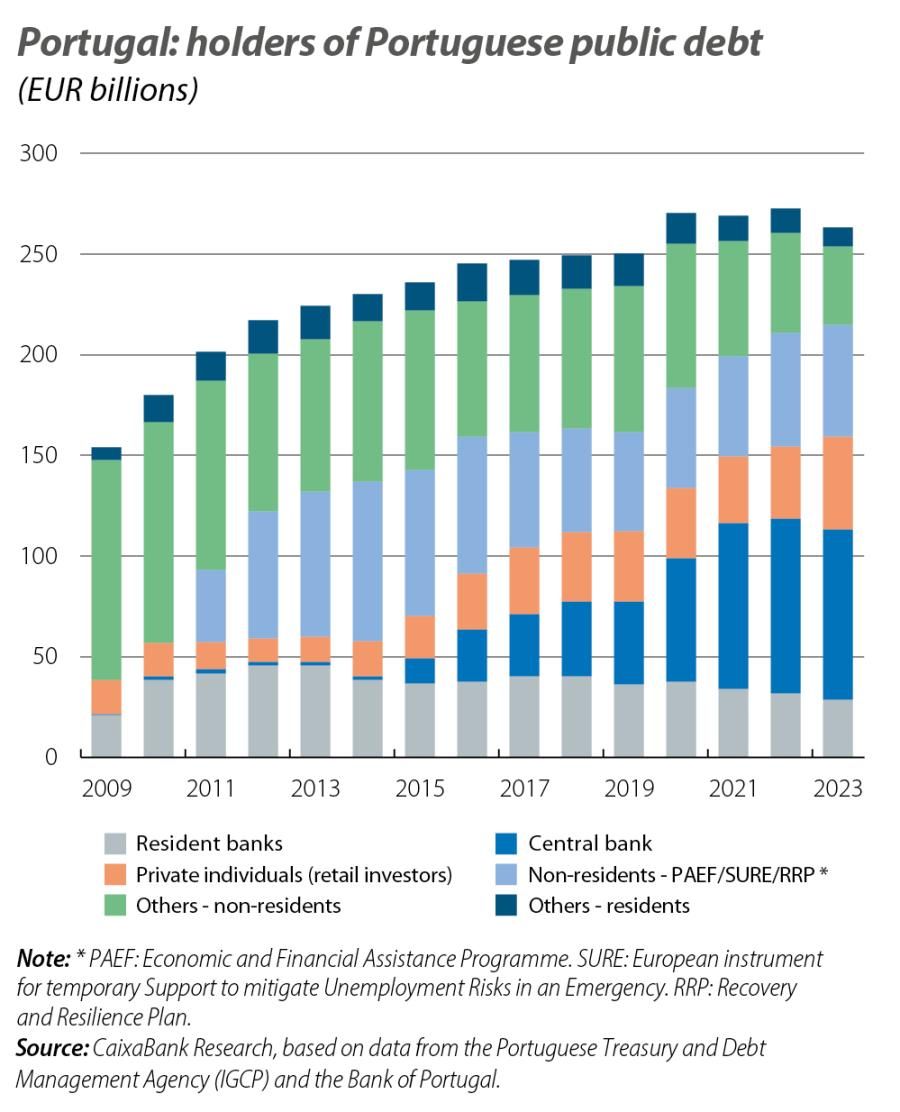

Finally, it is also worth noting the change that has occurred in the structure of holders of public debt. Another reason that can be argued for the increase in the value of Portuguese public debt securities is related to the lower volume of debt in circulation in the markets; in fact, in 2023, Portugal issued around 8.7 billion euros less in Treasury bonds and bills, reducing the outstanding balance of these instruments by around 7 billion euros. The reduced use of the market is partly explained by the significant increase in debt holdings among the retail public. Subscriptions (net of interest) of retail products exceeded 9.6 billion euros last year, fully offsetting the lower issuance of securities in the market. This has caused the portion of public debt that is held by resident individuals to increase from 13% in 2022 to around 17% at the end of 2023. This compares, for example, with around 2% in the case of Spain. This is also a matter very specific to Portugal’s public debt: in total, among private individuals, the central bank and official creditors (i.e. loans under the Financial Assistance Programme), the proportion of non-market debt exceeded 70% at the end of 2023 (compared to around 10% in 2010).

- 1. The reduction of public debt in 2023, both as a ratio and in terms of absolute value, is also explained by the early repurchases of public debt from banks and insurance companies, as well as the high allocation in CEDICs (special certificates of short-term public debt), a form of debt excluded from the Maastricht criteria (which increased by more than 8.4 billion euros in 2023).

- 2. At the time of writing, there was still no information available on the year-end data for the 2023 public accounts of the euro area as a whole. In Portugal, it is known that the public debt ratio stood 17.5 pps below the level of 2019.

With the gradual reduction in the size of its balance sheet, the ECB’s intervention in the debt markets will steadily fade.3 The question arises as to what impact this could have on Portugal’s cost of financing. The Treasury’s financing strategy for 2024, approved in December last year, includes the issuance of bonds worth around 20.7 billion euros, mainly through medium- and long-term instruments. The projected emissions in the market for this year exceed those recorded in 2023 (by just under 4.4 billion euros), but are below the amount issued in 2022 (by just over 4.3 billion euros).

In turn, some 8.5 billion euros in medium- and long-term bonds will reach maturity this year, some of which are in the hands of the ECB. In particular, for 2024, the central bank’s net purchases of Portuguese public debt are expected to be negative by 2.3 billion euros according to the IGCP.4 In this context, we estimate that the debt held by the central bank will fall from around 32% of GDP in 2023 to around 30% this year.

This means that, in net terms, Portugal will have to place around 9.8 billion euros in medium- and long-term public debt securities into the hands of private investors – something that ought to be possible without causing the risk premium to suffer. Interest rates are expected to remain relatively high, meaning that Portuguese government bonds should remain attractive to investors. This appetite for Portugal’s public debt is corroborated by the reception of recent bond issues, where demand outstripped supply by almost double.

At the same time, the recent upgrading of Portugal’s rating to risk level A by the major rating agencies increases the attractiveness of Portuguese debt to institutional investors, which tend to invest in debt issued by countries considered lower risk. In addition, by the end of this year Portugal could be reinstated into the FTSE World Government Bond Index, which only admits sovereign bonds that are assigned an A rating.

The diversification of the investor base is a very positive development for reducing financing costs and the vulnerability to external shocks and, therefore, promoting financial stability and increased liquidity in the debt market, making it more attractive.

In short, Portugal’s recent economic and financial performance has enabled a more favourable comparison with other European partners in terms of financing costs. In this context, the gradual withdrawal of the ECB should not put additional pressure on financing costs. However, it is important to keep in mind that the markets can quickly change their perception of an economy’s outlook, so it is essential that the right policies – notably those that shore up investor confidence – are maintained.

- 3. With regard to the APP, since July last year the ECB has not been reinvesting bonds that reach maturity. As for the PEPP, between April 2022 and June 2024, the ECB is reinvesting 100% of the bonds that reach maturity, but between July and December 2024 the ECB will allow 7.5 billion euros a month to mature, accelerating in 2025 with zero reinvestments.

- 4. According to information from the March 2024 investor presentation by the Portuguese Treasury and Debt Management Agency (IGCP).

- 1. The reduction of public debt in 2023, both as a ratio and in terms of absolute value, is also explained by the early repurchases of public debt from banks and insurance companies, as well as the high allocation in CEDICs (special certificates of short-term public debt), a form of debt excluded from the Maastricht criteria (which increased by more than 8.4 billion euros in 2023).

- 2. At the time of writing, there was still no information available on the year-end data for the 2023 public accounts of the euro area as a whole. In Portugal, it is known that the public debt ratio stood 17.5 pps below the level of 2019.

- 3. With regard to the APP, since July last year the ECB has not been reinvesting bonds that reach maturity. As for the PEPP, between April 2022 and June 2024, the ECB is reinvesting 100% of the bonds that reach maturity, but between July and December 2024 the ECB will allow 7.5 billion euros a month to mature, accelerating in 2025 with zero reinvestments.

- 4. According to information from the March 2024 investor presentation by the Portuguese Treasury and Debt Management Agency (IGCP).