Balance sheets: the not-so-visible normalisation of monetary policy

2025 should be the year of monetary policy untightening, with the ECB and the Fed lowering their interest rates to neutral levels (around 2% and 3%, respectively). These rate cuts will be accompanied by another, less visible normalisation: the reduction of their balance sheets, which have grown exponentially in the last 15 years.

2025 should be the year of monetary policy untightening, with the ECB and the Fed lowering their interest rates to neutral levels (around 2% and 3%, respectively).1These rate cuts will be accompanied by another, less visible normalisation: the reduction of their balance sheets, which have grown exponentially in the last 15 years.

- 1See the article «Monetary policy in 2025: dialling-back time» in the Dossier of this same Monthly Report.

What is going on?

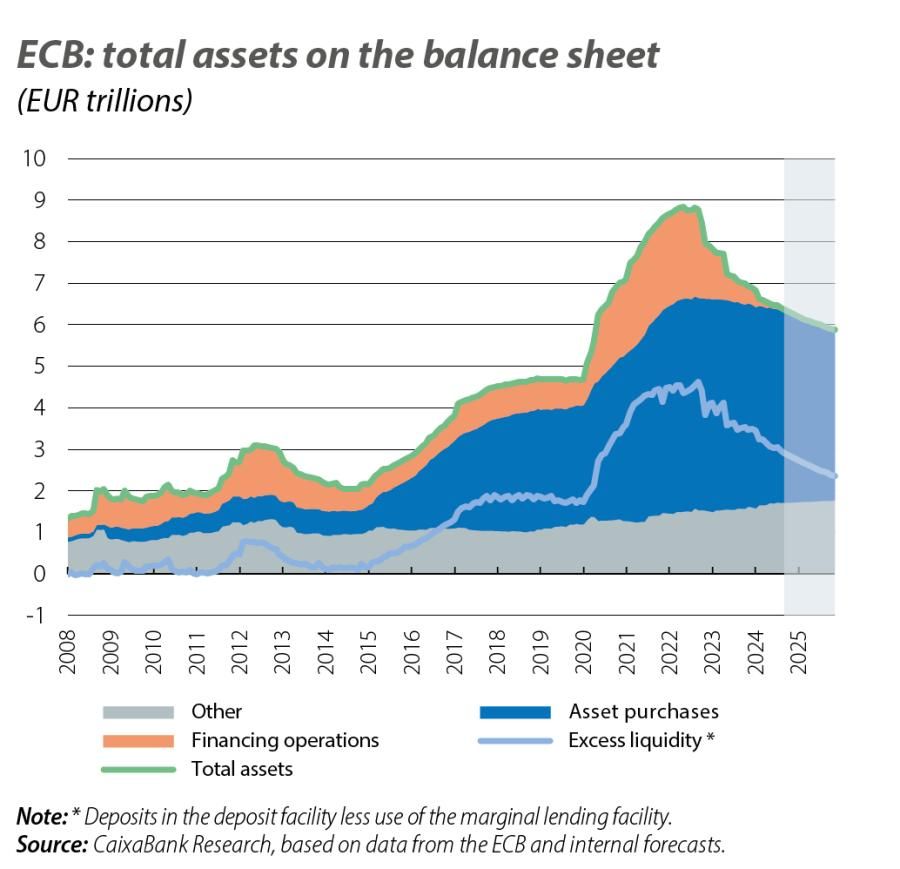

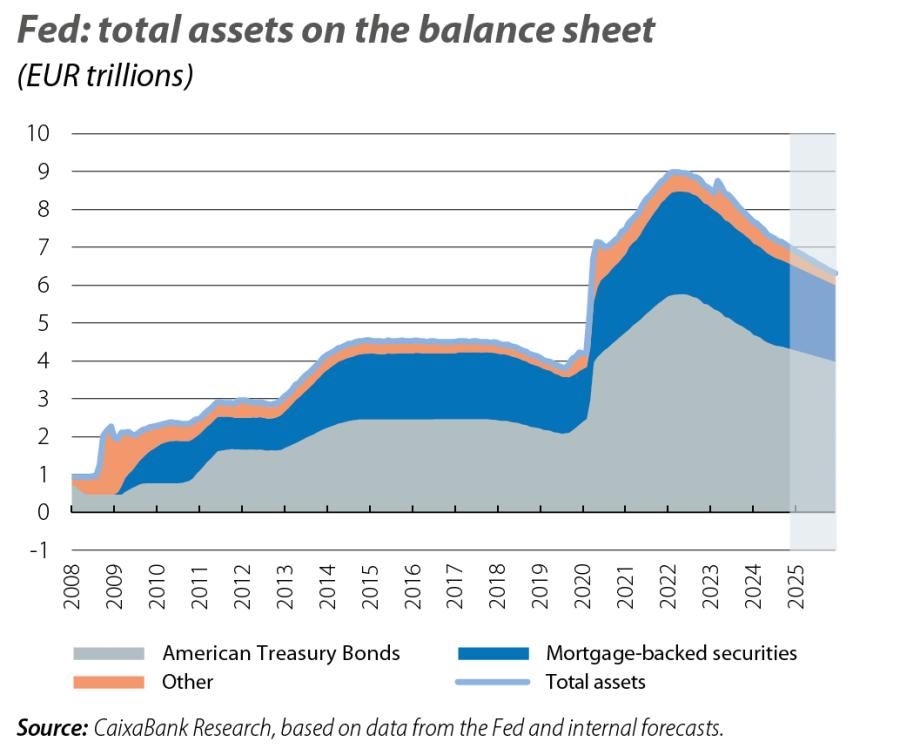

The balance sheets of the ECB and the Fed peaked in mid-2022, reaching almost 65% and 35% of the respective GDPs. As soon as they reached these highs, the inflationary crisis caused both central banks to end the asset purchases with which they had stimulated the economy and to begin to shrink the size of their balance sheets. This reduction process has accelerated and we estimate that, by the end of 2024, the ECB and Fed balance sheets will have decreased in size by 30% and 20%, respectively.

On both sides of the Atlantic, the contraction of the balance sheets has been carried out through a passive strategy that consists of not renewing the assets that reach maturity (but not selling assets before they reach maturity either).2 So far, the markets have digested this approach well, without causing any dysfunction or turbulence and without compromising the monetary easing that has begun with the latest rate cuts. In the case of the ECB, the reduction began with the end of TLTRO-III, liquidity injections into the banking system which were made available between 2019 and 2021 and matured between 2021 and 2024.3 In 2023, the process was accelerated with the end of reinvestments under the APP, the first major asset purchase programme launched in 2015 and with a portfolio amounting to almost 3.5 trillion euros: its reduction began with partial reinvestments in March 2023 and has continued passively since July 2023 with zero reinvestments.4 Finally, the balance sheet reduction process reached cruising speed in 2024 with the end of reinvestments under the PEPP, the purchasing programme associated with the pandemic that amounted to 1.7 trillion euros.5 With TLTRO-III already completed, and the APP and PEPP passively reducing in size, the ECB’s balance sheet will continue to shrink in 2025, when we estimate it could stand at around 40% of GDP.

- 2J. Ihrig, L. Mize and G.C. Weinbach (2017). «How does the Fed Adjust its Securities Holdings and Who is Affected?», Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2017-099, Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, explain how this process works in detail. In the case of the Fed, when a $100 Treasury bond matures, the assets on the Fed’s balance sheet are reduced by $100 (specifically, the heading «asset holdings of the Federal Reserve» is reduced). The Fed does not receive a cash income of $100, but rather the balance of the US Treasury account, within the Fed’s liabilities, is reduced by $100 (the Treasury has an account with the Fed, where it can deposit funds to manage transactions related to taxes, for the issuance and payments of sovereign bonds, etc.). If the Fed wanted this maturity of $100 to not affect the size of its balance sheet, it could reinvest that $100 in the purchase of a new bond, which would once again increase both the holdings of assets (within its assets) and the Treasury account balance (within its liabilities) by $100.

- 3TLTRO-III reached more than 2 trillion euros. The last operation remaining, for a sum of just 29 billion, matures in December 2024

- 4Initially, when a portfolio bond expired, the ECB allocated 100% of the principal received to new purchases, thus keeping the size of the bond portfolio stable. Between March and June 2023, the ECB reinvested only 15 billion euros per month (vs. average maturities of 32.6 billion), and since July 2023 it has not reinvested any of the 376.8 billion that has matured.

- 5The ECB reinvested 100% of maturities up until June 2024. In July, it began to allow around 7.5 billion euros per month to mature without reinvestment, and it will cease all reinvestments at the end of 2024.

In the case of the Fed, the reduction began in June 2022, when it stopped reinvesting the Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) that expire each month, with an initial maximum value of non-reinvestments of 47.5 billion dollars per month (30 billion in Treasury bonds and 17.5 billion in MBSs). This reduction accelerated in September 2022, reaching a peak of 95 billion per month (60 billion in bonds and 35 billion in MBSs),6 before finally slowing to 60 billion in June 2024 (25 billion in bonds and 35 billion in MBSs). This process has enabled the Fed to reduce its holdings of Treasury bonds by 1.4 trillion and those of MBSs by 0.4 trillion, to 4.4 trillion and 2.3 trillion, respectively. In 2025, we expect the Fed to maintain a similar pace7 and that, by the end of next year, its balance sheet will stand at around 25% of GDP.

What are the challenges?

We expect that the balance sheet reduction processes will be gradual and that the total assets held by the Fed and the ECB will remain well above their pre-pandemic levels. Nevertheless, this does not mean that the process will be free of challenges.

One of the questions is the relationship between the size of the central banks’ balance sheets and the abundance and distribution of liquidity in the financial system. In Europe, the reduction of the ECB’s balance sheet will still leave us with significant excess liquidity.8 Furthermore, anticipating the reduction in liquidity that will gradually become visible, not in 2025 but later, the ECB itself has revised its operating framework in order to avoid any future problems arising due to this lower liquidity.9

- 8Based on the rate of reduction of the APP and the PEPP, excess liquidity is expected to reach 2.4 trillion euros by the end of 2025. Historically, only when this figure has fallen below 350 billion have signs of low liquidity appeared (e.g. the 1-day interbank rate becoming decoupled from the deposit facility rate).

- 9See the Focus «The ECB, in the midst of a review» in the MR12/2023. In March 2024, the ECB officially introduced a system of liquidity on demand which enables abundant and well-distributed liquidity but with the central bank having a smaller footprint in the markets.

In the US, however, the situation is more uncertain. The Fed’s goal is a system of «ample» reserves, whereby they would be less abundant than in the past but sufficient to allow the financial system to operate without liquidity restrictions while also ensuring that the fed funds rate is not materially sensitive to day-to-day changes in the total volume of reserves. Precisely where this equilibrium lies is difficult to estimate. On the one hand, the reserves have declined to 14% of GDP (versus a peak of 20% in 2021) and the Fed has suggested that a level of 10%-11% would be a good target,10 meaning that there is still some way to go in the balance sheet reduction process. This is also suggested by an indicator produced by the New York Fed,11 which estimates the sensitivity of the fed funds rate to changes in reserves and still places that sensitivity at practically zero. On the other hand, frictions have appeared in the money markets, such as the more-than-20-bp spike in the SOFR in a single day in September,12 suggesting that liquidity may be less abundant than it might seem.

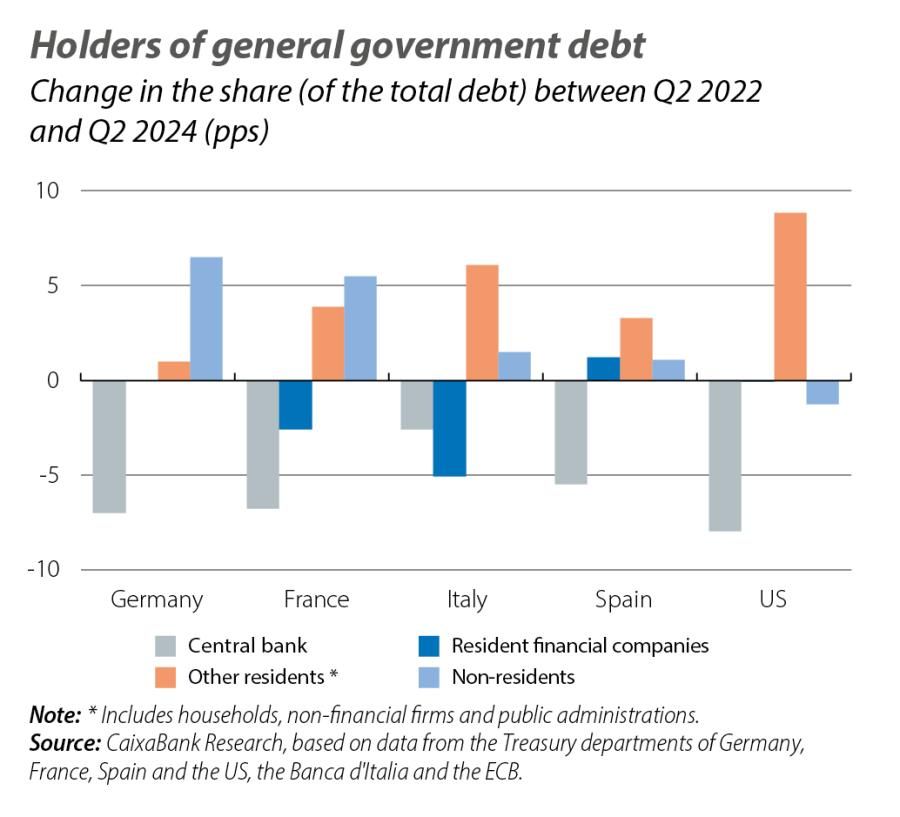

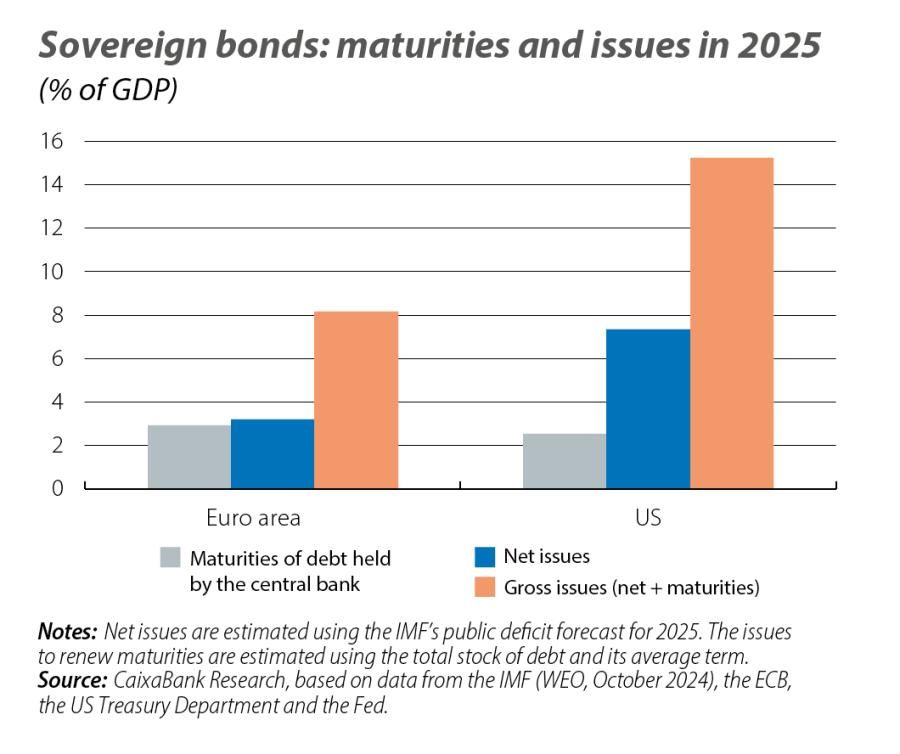

Finally, the withdrawal of the central banks’ asset purchases eliminates a major bond buyer from the secondary markets. Over the past two years, the decline in ECB and Fed debt holdings has been significant, but at the same time this gap has been largely filled by demand from private investors. This is an encouraging trend and one that is expected to continue in 2025, despite the scale of the purchases that the Fed and the ECB plan to cease, as the comparison with the expected volume of debt issues shows (see last chart).

- 10C. Waller. «A Conversation with Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller». The Brookings Institute, 2024.

- 11See G. Afonso, D. Giannone, G. La Spada and J.C. Williams (2022, revised in 2024). «Scarce, abundant, or ample? A time-varying model of the reserve demand curve». Staff Report nº 1019, Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

- 12This is the interest rate at which banks and other financial institutions take overnight financing and, therefore, it serves as a measure of how tight monetary conditions are.

In short, in 2025 we should see the co-existence of a gradual reduction in Fed and ECB benchmark interest rates (causing monetary easing) with a smooth decline in the size of their balance sheets and in the amount of excess liquidity. The balance sheet reduction process helps to shrink the footprint of both central banks in the financial markets,13 thereby mitigating the Fed and the ECB’s exposure to credit and duration risks. Also, although increasing the size of the balance sheets was a stimulus measure, their reduction in 2025 and in the years ahead is not expected to impose a monetary restriction that will interfere with the rate cuts or that will hold back the economy. Firstly, the balance sheet reduction process conducted during the course of 2022, 2023 and 2024 has been well received, and in these years the financial markets have taken the Fed and ECB benchmark rates (and not their balance sheets) as the guiding tool for monetary policy. Secondly, there are several reasons why the reduction and increase of their balance sheets do not have symmetric effects: (i) the balance sheet increases occur in turbulent times marked by disruptions in the functioning of the markets, while the reduction takes place in a stronger economic environment; (ii) the balance sheet increases serve to ensure that, in these turbulent times, the central bank makes clear its commitment to an accommodative monetary policy for a long time, whereas in the balance sheet reduction phase the Fed and the ECB have decoupled changes in their balance sheets from changes in rates, and (iii) the balance sheet increases are rapid and aggressive, while the reduction is slow and gradual, as the projections presented in this article show.

- 13This also helps alleviate shortages of collateral, thereby improving the functioning of markets such as that of repos, as well as reviving the financing markets.