The central banks’ response to the rebound in inflation(and the ECB’s inaction)

In 2021, inflation has reached levels not seen for many years in most economies. This phenomenon is dominating the current economic debate, mainly because of its implications for monetary policy. Our view, which is shared by the major central banks, is that the factors behind these high inflation rates are transitory in nature and should fade during the course of 2022.

In 2021, inflation has reached peaks not seen in many years in most advanced and emerging economies. For example, we need to trace back to 1990 to find US inflation above last October’s 6.2%, while in the euro area November’s 4.9% is the highest level since the series began. This phenomenon is attracting the full attention of the current economic debate, mainly because of the implications it has for monetary policy. Our view, which is shared by the major central banks, is that the factors behind these high inflation rates are transitory in nature and should fade during the course of 2022.

On the one hand, global energy prices have increased significantly and account for most of the rise in inflation. The main reason for this has been a perfect storm in the gas market caused by several factors, such as colder than normal temperatures, a lack of wind, lower hydroelectric generation, other one-off disruptions in the supply of gas in various countries, and increased demand for gas, especially in China. Individually, these factors would have had only a minor impact on the price of this fossil fuel, but together they have caused the price of gas to rise by +350% so far this year. This rise has pushed up the price of electricity in most countries, and given its magnitude and persistence this trend has also ended up affecting other fossil fuels, such as oil and coal. Prices in the financial markets reflect expectations that this situation could persist for a few more months still, but with the end of winter and the reduction in seasonal demand the energy markets will be less strained.

The mismatch between the demand and supply of many goods, which is visible in the bottlenecks caused by the sharp growth in demand around the world, is a second element also pushing up prices.1 Despite high uncertainty, this dynamic looks set to persist for several more months yet, and it could keep inflation high during the first half of the year. Nevertheless, it should fade during the course of 2022 as supply normalises and pent-up demand runs out. However, the emergence of new, mutated variants of the virus, such as Omicron, is a latent risk that could intensify the bottlenecks.

- 1. For more details, see the article «Bottlenecks: from the causes to how long they will last» in the Dossier of this same Monthly Report.

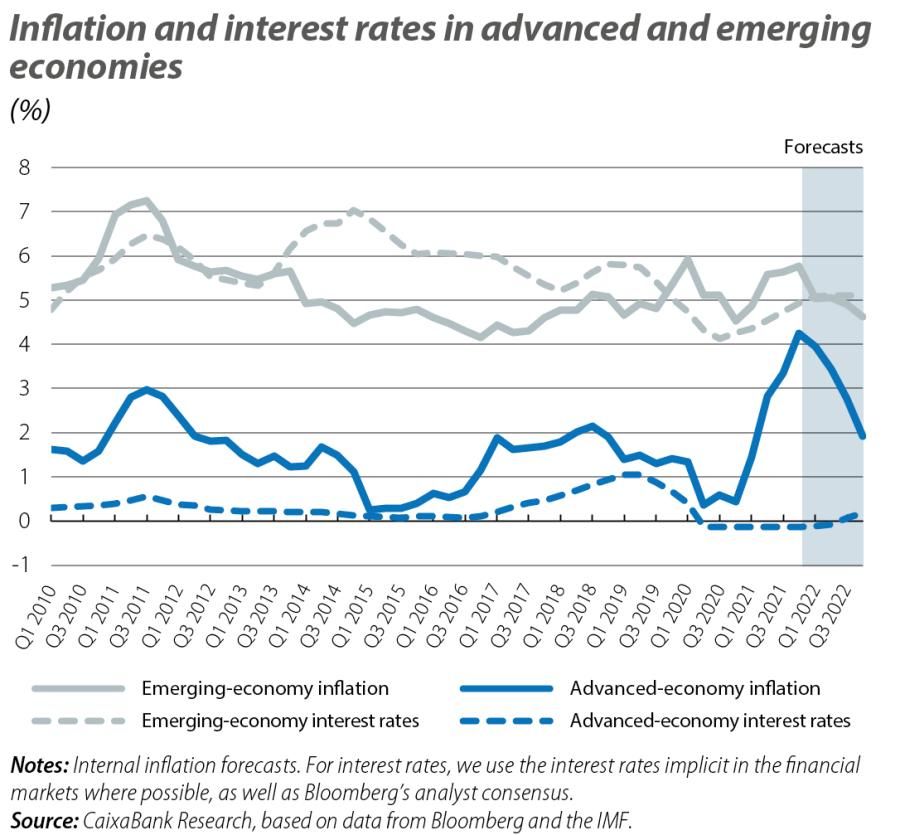

In the face of rising prices, a number of central banks have already begun to withdraw the monetary stimulus deployed after the outbreak of the pandemic. In particular, in many emerging economies the monetary authorities have already begun to raise rates, as these are countries where energy and commodity prices tend to have a more direct effect on inflation, given their greater relative weight in the price index. Thus, in 2021 the central banks of Russia, Brazil and Poland have raised interest rates by 5.75, 3.25 and 1.15 pps, respectively, and are expected to continue the cycle of rate hikes in 2022. In developed economies, rate hikes have been more contained and selective, and only the central banks of Norway, New Zealand and South Korea have raised rates (by 0.25 pps).

We believe that 2022 will be the year in which most central banks will withdraw the monetary stimulus and raise interest rates, both in advanced and in emerging economies, provided the new variants of the virus allow it. Thus, the financial markets anticipate four rate hikes by the Bank of England and that of Canada, three in the case of Australia and up to seven for New Zealand. Two 0.25-pp rate hikes are expected from the Federal Reserve, in line with our own forecasts, while in Frankfurt no interest rate changes are anticipated as explained below.

As we discussed in a recent article,2 the euro area economy, like that of Japan, is at a different point in the business cycle compared to the other economies mentioned above. Its core inflation, which excludes the energy and food components, stands at 2.6%, a far cry from New Zealand’s 4.8% or the US’ 4.6%. In addition to a widely varying core inflation, which is clearly higher in the core economies than in the periphery (see second chart), there is another peculiar feature: the base effect of the temporary VAT reduction applied in several countries in the second half of 2020. This factor is placing current inflation (both headline and core) at artificially high rates, and this will cease to be the case from January 2022.

- 2. See the Focus «On the normalisation of monetary policy» in the MR10/2021.

In this context, the ECB insists that the rebound in inflation is transitory and that it will not act to counteract it as long as it continues to believe that the second-round effects3 will be moderate and the aforementioned elements fade during 2022. Moreover, following the ECB’s strategic review and the shift in its forward guidance proposed in July, with the medium-term inflation target of 2%, it is highly unlikely that we will see a rate hike before the end of 2023.

Yet the ECB is not isolated from global inflationary dynamics and, together with the fact that the euro area economy will reach pre-pandemic GDP levels in Q1 2022, we believe it will also withdraw some of the monetary stimulus in 2022. Specifically, we estimate that net asset purchases in 2022 will amount to around 570 billion euros.4 This is a very considerable volume, even if it is 520 billion less than the purchases carried out in 2021, a year still heavily conditioned by the pandemic. These purchases, together with reinvestments of the assets at maturity, will enable the ECB to maintain an accommodative financial environment with which to support economic growth and continue to meet Member States’ funding needs. It should also be noted that in 2022 the issuer limits will no longer be such cause for concern as they were in the pre-pandemic world. With the rise in public debt following the outbreak of the pandemic, the ECB has scope to maintain the rate of purchases which we expect to see up until the end of 2023 without exceeding these limits.

- 3. I.e. how high inflation rates today could translate into higher inflation rates in the future. Some studies suggest that second-round effects have lost relevance in recent years, although it is true that the particular nature of the crisis and the economic recovery triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic could lead to a change in this dynamic. See, for example, C. Borio, et al. (2021). «Second-round effects feature less prominently in inflation dynamics».

- 4. Specifically, we believe that net asset purchases under the PEPP during Q1 will be at a slower pace than in the last quarter of 2021 and will cease in March. We believe that the APP will then take on a more prominent role and that the net monthly purchases could go from the current level of 20 billion euros to 40 billion. In addition, there is speculation that the ECB could incorporate some flexibility into the level of purchases under the APP, announcing a target for the volume of purchases to be made throughout the year as a whole rather than a monthly purchase rate.

This whole scenario, however, is subject to much uncertainty. New variants of the virus, such as Omicron, will continue to weigh on the ECB’s balance of risks and could condition economic activity in 2022, along with inflation.

- 1. For more details, see the article «Bottlenecks: from the causes to how long they will last» in the Dossier of this same Monthly Report.

- 2. See the Focus «On the normalisation of monetary policy» in the MR10/2021.

- 3. I.e. how high inflation rates today could translate into higher inflation rates in the future. Some studies suggest that second-round effects have lost relevance in recent years, although it is true that the particular nature of the crisis and the economic recovery triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic could lead to a change in this dynamic. See, for example, C. Borio, et al. (2021). «Second-round effects feature less prominently in inflation dynamics».

- 4. Specifically, we believe that net asset purchases under the PEPP during Q1 will be at a slower pace than in the last quarter of 2021 and will cease in March. We believe that the APP will then take on a more prominent role and that the net monthly purchases could go from the current level of 20 billion euros to 40 billion. In addition, there is speculation that the ECB could incorporate some flexibility into the level of purchases under the APP, announcing a target for the volume of purchases to be made throughout the year as a whole rather than a monthly purchase rate.