Europe and the mission to decouple from Russian oil: an achievable goal in the short term

The energy crisis has served as an incentive within the EU to accelerate the transition to energy sources that are more environmentally friendly and less dependent on fossil fuels, but this is seen as more of a medium-term goal.

Since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, the West has set itself the objective of reducing its dependence on imports of fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas) from Russia.1 In addition to a desire to reduce energy dependence on a single major supplier, this goal was set with the aim of weakening the Russian economy.2 The first steps were taken by the US and Canada by imposing a veto on imports of Russian oil and gas in March. In Europe, however, it took longer to reach a decision, given that Europe has historically been Russia’s main market for oil and gas exports (30% and 40%, respectively). Finally, in June, all EU Member States signed a sanctions package3 which included a ban on the purchase, import or transfer of oil and certain petroleum products from Russia to the EU. The restrictions will be applied gradually, between December and February 2023, and will affect 90% of the crude oil and refined products which Russia delivers to the European bloc. However, a temporary exception was also agreed upon for imports of crude oil supplied via pipeline to some Member States (such as Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia) which are highly dependent on Russian supplies and which lack viable alternatives in the short term. In addition, at the end of September, the proposal for an eighth package of sanctions on Russia was discussed within the EU, which envisages setting a cap on the price of Russian oil.

- 1. Russia is one of the leading global powers when it comes to the production and export of fossil fuels, ranking among the top three countries in the world.

- 2. Up until 2021, 40% of Russia’s Federal Budget was fed by revenues generated by taxes and export tariffs on gas and oil.

- 3. Sixth EU sanctions package on Russia (June 2022). See Publications Office (europa.eu).

During the first six months of the war, the EU remained the main buyer of Russian fossil fuels, although its share of imports of fossil fuels from Russia gradually reduced from 70% in March to 54% in August. This decline has been largely driven by a reduction in gas purchases, which intensified in August with the slowdown and subsequent cut-off of supplies through Nord Stream 1, as well as lower purchases of coal, which has been the subject of an embargo by EU countries also since August.4 Similarly, in the case of oil, Europe’s dependence on imports from Russia has been gradually declining. According to data from the International Energy Agency (IEA), the imports of Russian crude oil as a proportion of the total oil imports of European OECD countries have gone from a peak of 26% in March, driven by fears of supply shortages, to 15% in June, as a result of the financial and trade sanctions imposed on Russia. Thus, the share of Russian oil imports averaged 19.6% in the first half of 2022 (21.4% in the first half of 2021).

It should be noted that, with the lower purchases by Europe, there has been a reorganisation of the international trade in Russian fossil fuels. The latest data suggest that China has displaced Germany as the main buyer of Russian oil and coal. Also, countries such as India and Egypt, which imported hardly any oil from the Urals before the war, have emerged as major trading partners,5 having imported more Russian oil than even the major euro area countries in the two-month period of July to August.

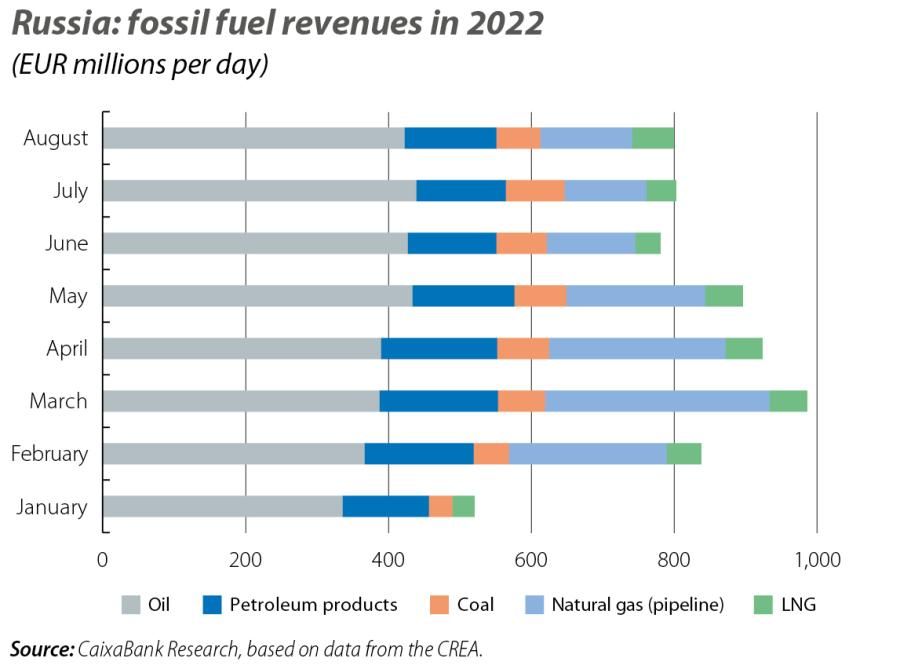

This redistribution in the trade of Russian crude oil flows has also been reflected in the evolution of Russia’s income from the sale of fossil fuels to the rest of the world. Despite the Western restrictions and the moderation in global economic activity, the participation of these new buyers has allowed the country’s daily revenues from oil exports to remain above pre-war levels in a context of high prices on the international markets, despite their decline compared to March when the Brent barrel price peaked (128 dollars).

- 4. Fifth EU sanctions package on Russia (April 2022). See Publications Office (europa.eu).

- 5. According to data from the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), India and Egypt are engaged in the practice of refining the oil they buy from Russia before then exporting it to the rest of the Western world, to countries such as the US and Australia.

EU efforts to reduce gas consumption are being offset by a larger aggregate consumption of oil and coal (8% and 7% year-on-year in the first half of the year, respectively, according to Eurostat). This increase has occurred in a context in which imports from Russia have been gradually reduced and even banned, as in the case of coal, so purchases of energy supplies from other countries have increased. For example, South Africa and Colombia have become the main suppliers of coal. In the case of oil, meanwhile, in July daily imports from Saudi Arabia and Iraq increased by 90% compared to January 2022, while imports from the US were at peak levels. In the coming months, dependence on Russian oil will continue to be reduced: it is estimated that with the embargo on Russian crude oil coming into force, by the end of this year EU oil imports from Russia will fall to 600,000 barrels a day, compared with 3 million barrels a day prior to the conflict and 2.3 million in July. Despite this, all the indicators suggests that Europe’s oil needs will be met in the short and medium term. Not in vain, unlike gas, which is critically dependent on physical infrastructure for its transportation, oil can be transported easily by sea, which makes it easier to replace Russian imports in the short term. In addition to the supply of oil from OPEC countries and the US, international associations such as the IEA have shown their willingness to re-release some of their strategic crude oil reserves, as they did at the beginning of the war. As for the implications for prices, the fact that there are alternatives on the supply side does not necessarily mean we will see them fall. Indeed, OPEC countries have expressed a desire to maintain prices at around 80 to 90 dollars a barrel, which is above the historical average and will keep the upward pressure on global inflation rates.

In the longer term, it is clear that the energy crisis has served as an incentive within the EU to accelerate the transition to energy sources that are more environmentally friendly and less dependent on fossil fuels. However, this is seen as more of a medium-term goal, suggesting that crude oil imports will remain a major component of Europe’s energy needs for several years to come.

- 1. Russia is one of the leading global powers when it comes to the production and export of fossil fuels, ranking among the top three countries in the world.

- 2. Up until 2021, 40% of Russia’s Federal Budget was fed by revenues generated by taxes and export tariffs on gas and oil.

- 3. Sixth EU sanctions package on Russia (June 2022). See Publications Office (europa.eu).

- 4. Fifth EU sanctions package on Russia (April 2022). See Publications Office (europa.eu).

- 5. According to data from the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), India and Egypt are engaged in the practice of refining the oil they buy from Russia before then exporting it to the rest of the Western world, to countries such as the US and Australia.