Analysis of the emerging European economic cycle

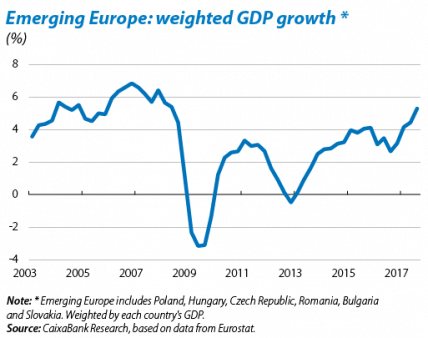

Eastern Europe (EE) is growing strongly. Latest GDP growth figures have not been seen in these countries for years (see the first chart). This has raised some eyebrows. Is such a high rate of growth sustainable? This article examines the factors behind the economic upswing in emerging Europe. We will see that, although the economic boom is closely linked to the strong EU economy, idiosyncratic factors have also come into play.

An analysis of the current cycle of the EE economies can be divided into two parts. On the one hand, EE is a very open economy with its main trading partner, the EU, taking around 75% of its total exports.1 As economic activity in the EU has gained momentum, it has boosted EE exports. Another key factor contributing to higher growth in EE is the fact that it has received EU structural funds.2

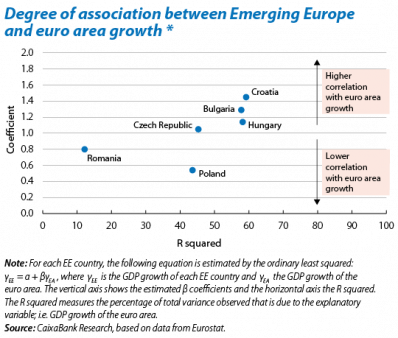

However, the EU does not explain by itself the entirety of the economic cycle of emerging Europe. Proof of this is the relationship between GDP growth in each of the EE economies and the euro area.3 As can be seen in the second chart, although the ratio between the GDP of each EE economy and that of the euro area is generally one to one (1 pp more GDP growth in the euro area is associated with 1 pp more growth in each EE country4), the variance due to the euro area’s GDP barely reaches an average of 50% of the total variance.

So what other factors explain the EE cycle? At present there are two particularly important ones: fiscal policy and monetary policy. EE governments have taken a clearly expansionary stance since 2015 (see the third chart). As discussed in more detail in the article «Political risk in emerging Europe: how much should we be concerned?» in this Dossier, this stance is at least partly due to the rise of populist policies that are being implemented mainly in Poland and Hungary. The plans announced by the respective governments so far suggest this trend will continue in the coming years.

Regarding monetary policy, the benchmark interest rate in most EE countries is at an all-time low, thereby supporting growth in demand.5 However, inflation is likely to rise faster than expected, even though it is still around the monetary authorities’ target at present. This is because of the strong growth recorded in economic activity and wages and the expansionary tone of fiscal policy.6 Soaring inflation could force monetary authorities to raise interest rates faster than previously announced in order to stop their economies from overheating. This suggests that monetary policy can be too accommodative in the current context. It is therefore illustrative to compare the benchmark interest rate for each country with the rate predicted by a simple Taylor rule. As can be seen in the fourth chart, in all cases the predicted rate is higher than the real rate.7

Strong growth is therefore expected to continue in EE over the coming quarters as the abovementioned factors will boost economic activity. Nonetheless, growth will ease slightly should the monetary authorities begin to withdraw the current stimuli.

Beyond a short-term analysis, it is also revealing to examine whether the region’s good momentum can be sustained in the medium and long term. An initial analysis of how the current expansionary phase is developing is encouraging since, as discussed in the article «Emerging Europe: growth with fewer risks» in this Dossier, EE countries are managing to maintain a high growth without accumulating macroeconomic imbalances.

However, the region still faces considerable challenges, particularly how EE might fit into the EU. This issue is tackled in the article «The dividends of integrating emerging Europe within the EU» in this Dossier. The main claim by this article is that EE has benefited greatly from its integration within the EU, although this boost has begun to wane. Reversing this trend will depend to no small extent on the degree of commitment of EE countries to supporting the construction of Europe. Otherwise there is a risk of countries such as Poland and Hungary becoming more populist, potentially resulting in a less favourable investment climate, both domestically and internationally. However, as discussed in the aforementioned article «Political risk in emerging Europe: how much should we be concerned?», the risks associated with a rise in illiberal democracies remain contained, at least for the time being.

The biggest challenge comes from the EE’s production model. Leading up to the financial crisis, a significant percentage of economic growth was due to improvements in total factor productivity (TFP), largely because of the region’s integration within the global economy and, in particular, in euro area countries. Unfortunately this source of growth will gradually diminish. In fact, since 2009 TFP’s contribution to growth has decreased markedly while the contribution made by capital accumulation has grown.8 Since growth based on the accumulation of production factors is limited in scope, the pressure for EE to alter its production model is likely to increase, moving from a model still highly dependent on cheap labour to one based on higher value added. This challenge may not be new – but is there an emerging region better prepared to tackle it?

Oriol Carreras Baquer

Macroeconomics Unit, Strategic Planning and Research Department, CaixaBank

1. In 2016, in a GDP-weighted average, the economies of Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Romania, Bulgaria and Slovakia had a ratio of total imports and exports to GDP that was 34.4 pp higher than the euro area.

2. For more details on the issue of the Structural Funds allocated to EE, see the article «The dividends of integrating emerging Europe within the EU» in this Monthly Report.

3. The euro-area aggregate is used instead of the EU aggregate since the EU includes EE countries.

4. Poland is the main exception, which is to be expected given the relative weight of its domestic market.

5. The central banks of Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary allow their exchange rate to fluctuate freely in the market. In particular, between 2013 and April 2017 the Czech Republic maintained its commitment to keep the koruna at a minimum exchange rate of CZK 27 per euro. Such a measure became effective in combating the risk of deflation and was abandoned once the central bank deemed the risks had disappeared.

6. In Q3 2017, wages grew 5% year-on-year in Poland, 7% in the Czech Republic, 12.5% in Hungary and 15.6% in Romania.

7. The Taylor rule used in this article relates the benchmark interest rate to its own lag, the difference between inflation and the historical average of inflation, and the difference between GDP growth and its historical average.

8. The TFP has gone from representing approximately 60% of growth over the period 1998-2008 to just under 40% between 2009 and 2016. For these calculations, a production function has been assumed with two factors of production: capital and labour. In addition, contributions have been calculated assuming the share of return on capital out of the countries’ total income is 40%.