Savings and COVID-19: how far will Europe’s saving fever go?

Analysing European consumers’ saving patterns at this time is key, since a revival of consumption will serve as one of the pillars that will support the economic recovery after the coronavirus.

- The increase in bank deposit volumes in European economies indicates a substantial increase in savings. The «pent-up savings» effect resulting from the lockdown is expected to be quickly undone, but saving driven by uncertainty will persist until the outlook improves.

- Both saving patterns during the 2008 financial crisis and a statistical exercise suggest a high increase in the euro area’s savings rate in 2020, which will be partially undone in 2021. This phenomenon could be particularly accentuated in the economies hardest hit by the COVID-19 outbreak.

Analysing European consumers’ saving patterns at this time is key, since a revival of consumption will serve as one of the pillars that will support the economic recovery after the coronavirus. At present, we already have macroeconomic data suggesting substantial changes in saving habits following the virus’ arrival (see first chart). Volumes of bank deposits in the major European economies increased significantly in both March and April. In Spain, for instance, the increase amounted to 20 billion euros in March-April (equivalent to 1.6% of GDP in 2019), while in France it was 45 billion (1.9% of GDP). In Germany, the increase reached 16 billion (0.5% of GDP).

This increase in deposits appears to indicate a significant rise in savings. This is natural in the short term: on the one hand, there is a «pent-up savings» effect, since the options for consumption have been considerably reduced with the lockdown. On the other hand, there is also a precautionary saving factor: usually, in demanding circumstances like the current one, households save more faced with the uncertainty over what the future holds for their work and finances and to prepare for potential unforeseen events.

Looking ahead to the next few months, it is quite possible that the «pent-up savings» effect will be undone as the economy is reactivated in the new normal. In contrast, precautionary saving will continue to weigh down on consumption, as uncertainty over the economic outlook and the possibility of further outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 will remain high.

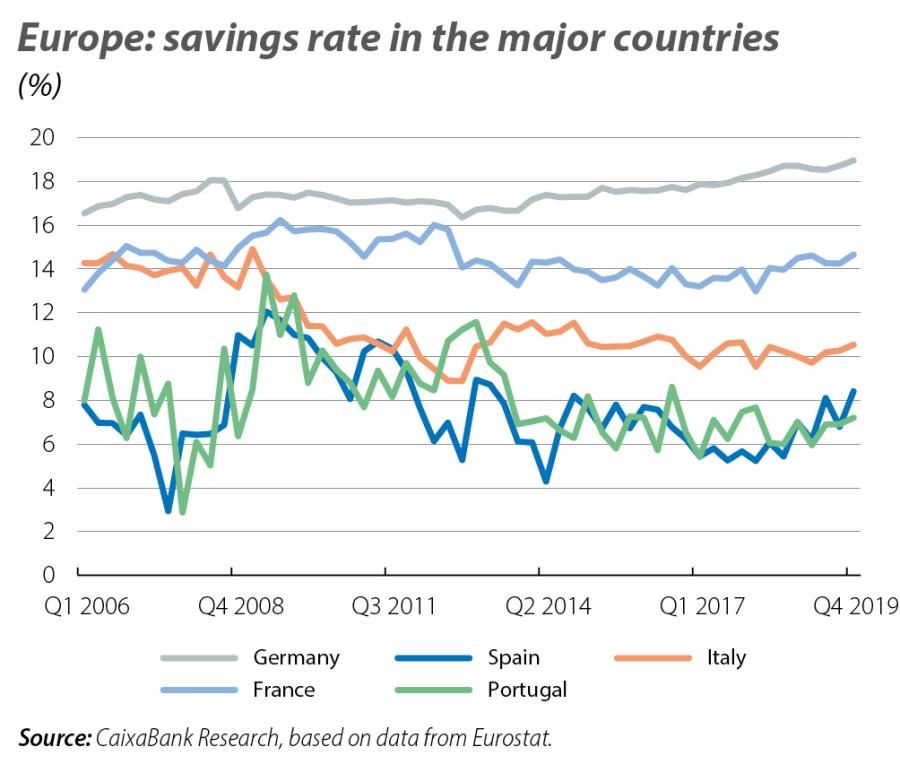

The 2008 financial crisis is a good reference point for analysing what happens to saving habits in times of uncertainty and economic hardship and, therefore, it serves to shed some light on what might happen in the current circumstances. In the euro area, the household savings rate (savings divided by gross disposable income) experienced a relatively modest rise between 2008 and 2009, and by 2010 this increase had already been undone. However, in the economies hardest hit by the crisis and with more modest pre-crisis savings rates, such as Spain and Portugal, the rise between 2008 and 2009 was much higher (+3.6 pps and 4.5 pps, respectively) and the savings rate reverted to pre-crisis levels much later (in 2012 in Spain and in 2014 in Portugal). This contrasted with the relative stability in the savings of German households.

This difference between Mediterranean and Northern countries (the latter save more and their savings rate fluctuates less) may be linked to cultural factors, such as differences between the Catholic and Protestant religion1 or citizens’ differing degrees of patience. For instance, a study published by the ECB shows that German-speaking households in Switzerland have an 11-pp higher probability of saving than similar households in nearby French-speaking areas, due to the fact that the former tend to place greater value on income they will receive in the future.2

In the 2008 crisis, precautionary saving played an important role; not in vain, according to one study,3 this type of saving was responsible for at least 40% of the changes in saving habits that occurred in advanced economies (according to the same study, the rest was due to interest rates, public transfers and reduced wealth, in equal proportions). In the current scenario, the unprecedented magnitude of the decline in economic activity and the high degree of uncertainty point towards a contraction in consumption that would lead to a significantly higher rise in the savings rate in 2020 than that seen in 2009, which would then begin to be undone in 2021.

Finally, we looked at what the predicted savings rate would be based on our forecasts for growth, unemployment and the European reference rate, controlling a measure of macroeconomic volatility.4 For the euro area, the prediction indicates an increase in the savings rate from 13.0% in 2019 to around 20% in 2020 (a record level), and a fall in 2021 down to 14.0%. The forecasts produced by major institutions such as the European Commission paint a similar picture, predicting an increase in the savings rate up to record levels in 2020 in the euro area (reaching 19.4%) and a fall in 2021 that would bring it down to 14.0%.

This increase in 2020 may seem exaggerated, but it is in fact consistent with the European Commission’s forecasts for the variables that determine the savings rate. In particular, they expect a very sharp fall in consumption (of around 9%) but only a very moderate drop in gross disposable income (GDI, of less than 2.0%).5 However, if the fiscal boost ends up failing to live up to expectations, the drop in GDI could be greater than currently anticipated, which would somewhat temper the surge in the savings rate.

The rise in savings rates in the hardest hit economies, such as Spain and Italy, could be particularly high. However, come 2021, the recovery in economic activity and the reduced uncertainty should help these economies to undo much of the increase in savings.

In short, precautionary saving has come to stay, at least until the uncertainties surrounding the coronavirus dissipate. At the current juncture, these uncertainties are unusually high, meaning that we will probably have to wait some time before European households are as spendthrift as just a few months ago.

- 1See B. Arruñada (2004). «The economic effects of Christian moralities». Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

- 2See B. Guin (2017). «Culture and household saving». Working Paper Series nº 2069. European Central Bank.

- 3See A. Mody, F. Ohnsorge and D. Sandri (2012). «Precautionary savings in the great recession». IMF Economic Review, 60(1), 114-138.

- 4We use a linear regression for the major European economies with panel data that include fixed country and year effects. The R^2 of the model is 88%.

- 5Indeed, the European Commission does not have aggregate forecasts for GDI for the euro area as a whole, but using forecasts for the various individual economies we have built a weighted average for the entire euro area.