The decoupling of the US and China accentuates the fragmentation of the global economy

The data from recent quarters show growing evidence of two major phenomena: the slowdown in the trade of goods, but not in services, and the growing fragmentation of global trade and production. At the epicentre of it all is China, with its increasingly key role in global manufacturing, which is decoupling from the United States.

The data from recent quarters seem to support the hypothesis that globalisation is transforming relative to the form is has taken in the previous three decades. These data show growing evidence of two major phenomena: the slowdown in trade in goods, but not in services, and the growing fragmentation of global trade and production. At the epicentre of it all is China, with its increasingly key role in global manufacturing as it produces ever more sophisticated goods (which favours its decoupling from other economies in a challenging geopolitical time), and which is decoupling from the US through an ever-increasing number of channels.

From a globalisation of goods... to one based on services?

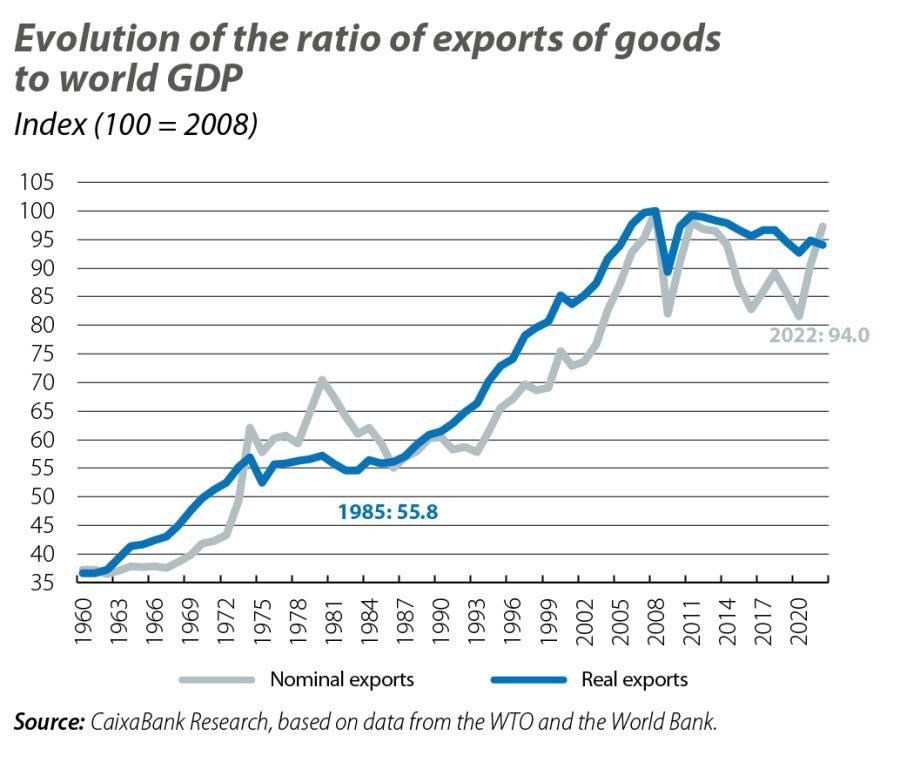

In 2023, the global trade in goods continued the gradual slowdown that had begun in the last decade with China’s transition towards a greater role of domestic consumption. The figure for 2023 is mainly explained by the contraction of trade in Europe, which is still weighed down by high energy prices. This slowdown, however, was not observed in the case of trade in services, which continued to grow at high rates (global services exports in current terms grew by 8.4% in 2023, compared with an average annual growth of 4.6% between 2012 and 2019). Although trade in services still represents a much smaller share of global trade than trade in manufactured goods, at around 7.5% and over 15% of global GDP, respectively, the gap has narrowed (in 2008 they accounted for 6.3% and 16.4% of world GDP, respectively).

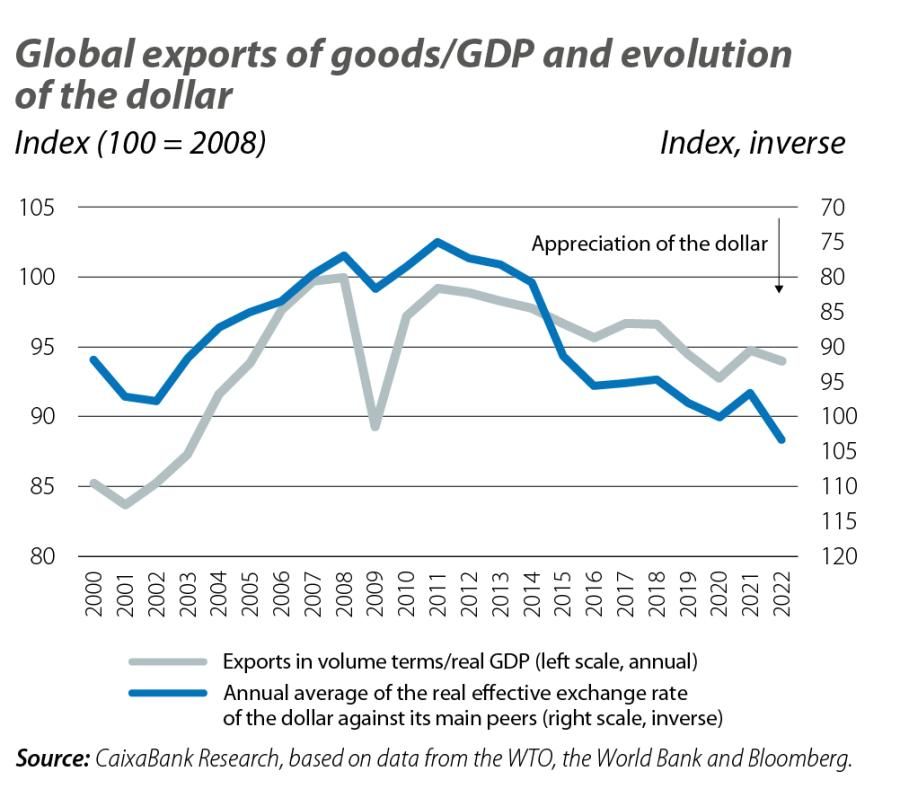

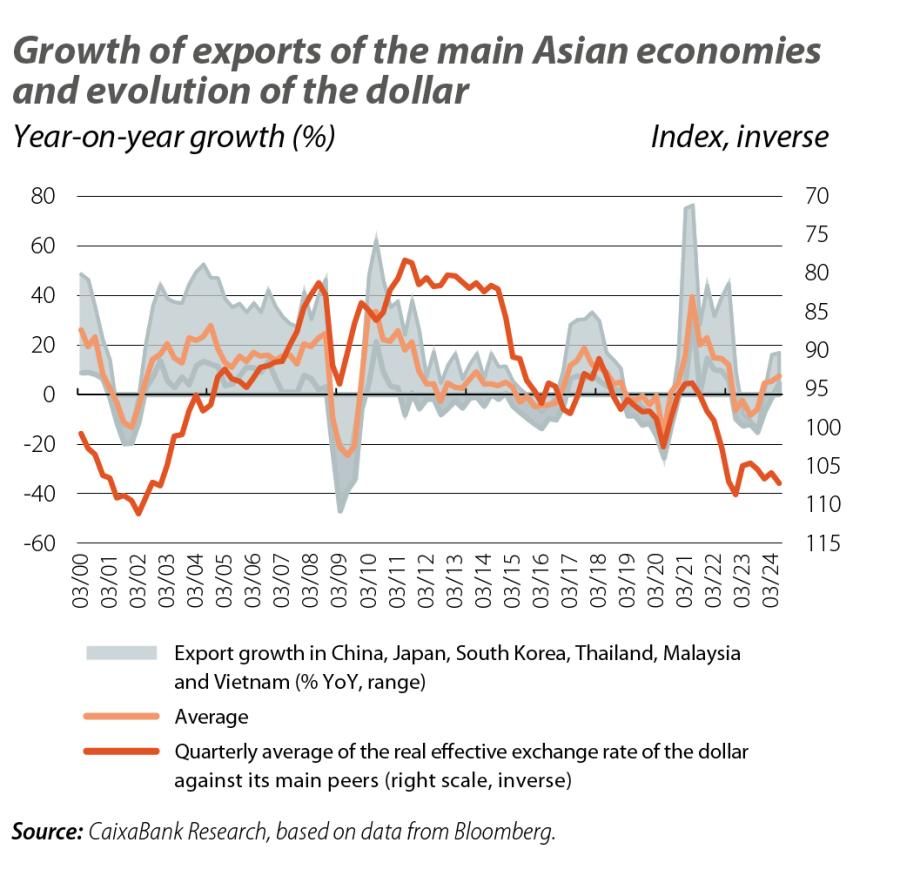

On the other hand, the strength of the dollar and, in general, the tightening of financial conditions throughout 2023 was an additional constraint for the growth of trade in goods. This is because it tends to hinder the financing of complex production and export processes, as we already explained in our first review of the state of globalisation.1

- 1See the Focus «¿Quo vadis, globalisation? (part I): the long slowdown», in the MR10/2023.

In this regard, if the rate cuts by the Fed and other central banks materialise in the coming quarters as expected, then we will see a steady easing of global financial conditions and the depreciation of the dollar seen in recent weeks is likely to continue. This, in turn, would favour an improvement in global trade in goods in both 2024 and 2025 (the WTO expects trade in goods to grow by 2.6% and 3.3% annually in these two years, respectively). Global export volume data for Q1, as well as trade data for Asian countries up until the summer, are already showing signs of improvement in the current year to date.

The global economy shows signs of fragmentation across all sectors and metrics

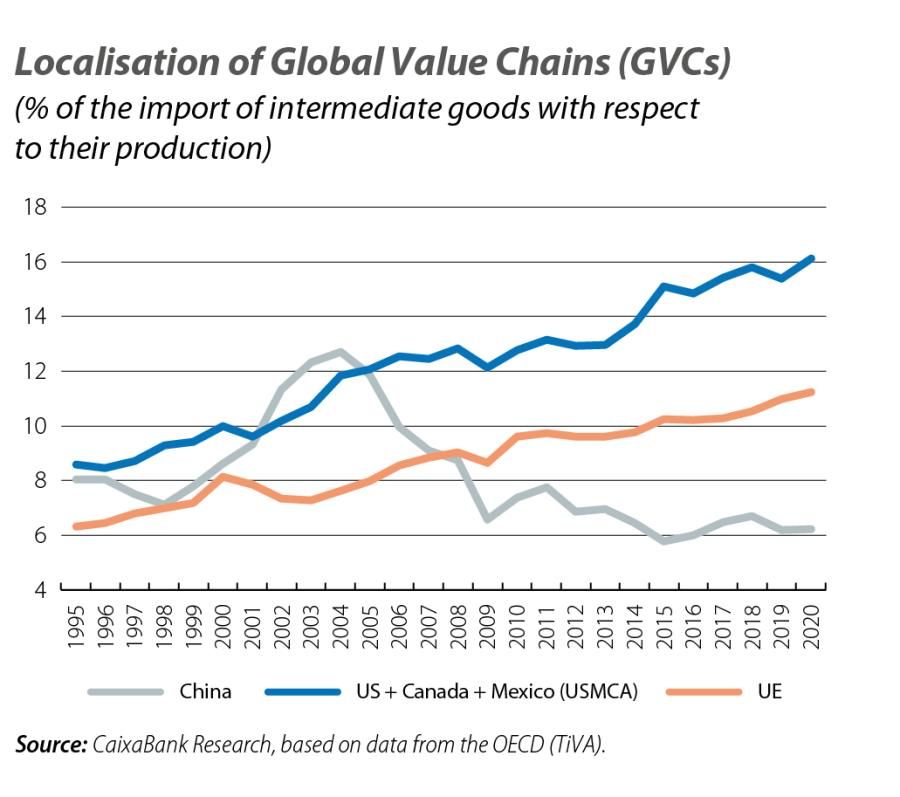

In addition to the slowdown in trade in goods, there is also evidence of further fragmentation of trade and global value chains (GVCs). Several studies have identified the lower levels of trade between geopolitical blocs since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, with intra-bloc trade growing at a faster rate than inter-bloc trade.2 Similarly, the decoupling between China and the US is continuing its course, and trade in goods and services between the two countries between 2018 and 2024 so far grew 25 pps less than US trade with the rest of the world (Mexico being the main beneficiary).

- 2See M. Blanga-Gubbay and S. Rubínová (2023). «Is the global economy fragmenting?». WTO Staff Working Papers ERSD-2023-10, World Trade Organization (WTO), Economic Research and Statistics Division.

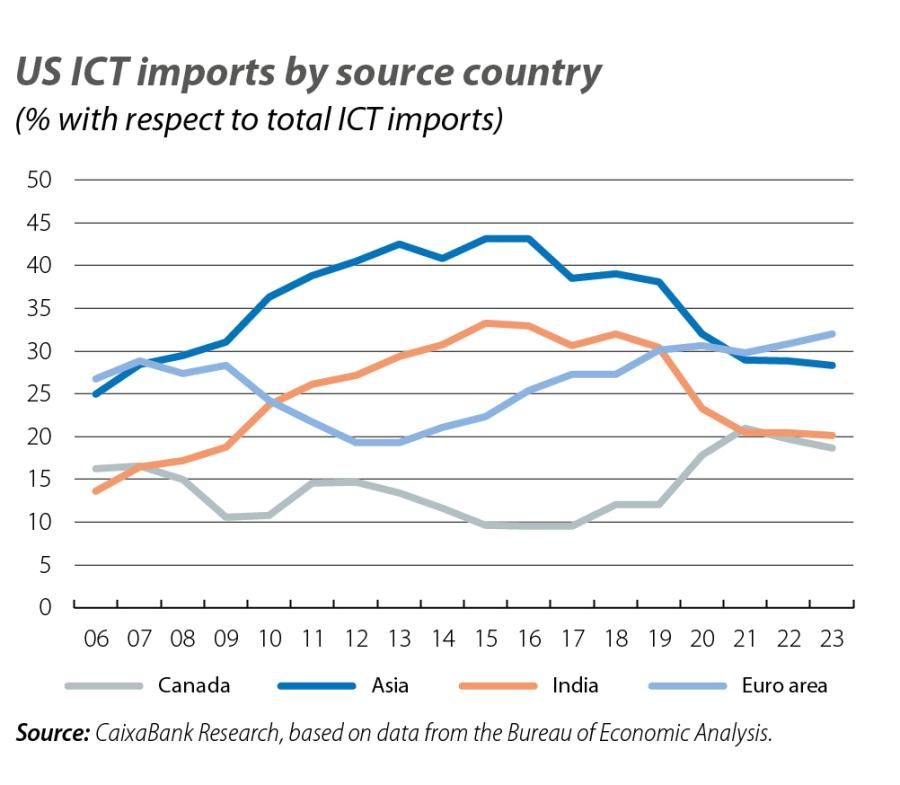

These signs of fragmentation are not only evident in the case of trade in goods. The US is importing higher-value-added services predominantly from countries that are located nearby and are politically aligned. Its imports of ICT services (ranging from IT activities to financial services) from other developed countries, such as the euro area and Canada, have steadily increased since 2018, to the detriment of Asian countries, mainly India.

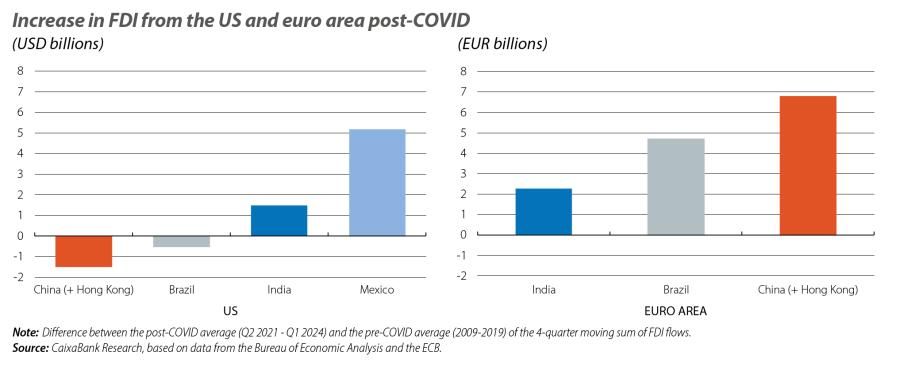

Foreign direct investment (FDI) flows are also being affected by this fragmentation and are being reorienting towards neighbouring countries. Indeed, this trend has been increasing in recent years and is particularly pronounced in sectors that are sensitive to the digital and green transitions.3 This trend is evident in flows from the US to China (and vice versa), although euro area firms have even increased their investment in China in recent years. Also with regard to FDI, the main beneficiary of the China-US decoupling is Mexico, which is set to benefit greatly from the subsidies included in the US’ Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

- 3See IMF. Research Dept. (2023). «Chapter 4: Geoeconomic Fragmentation and Foreign Direct Investment». World Economic Outlook, April 2023: A Rocky Recovery.

China’s size distorts the global picture

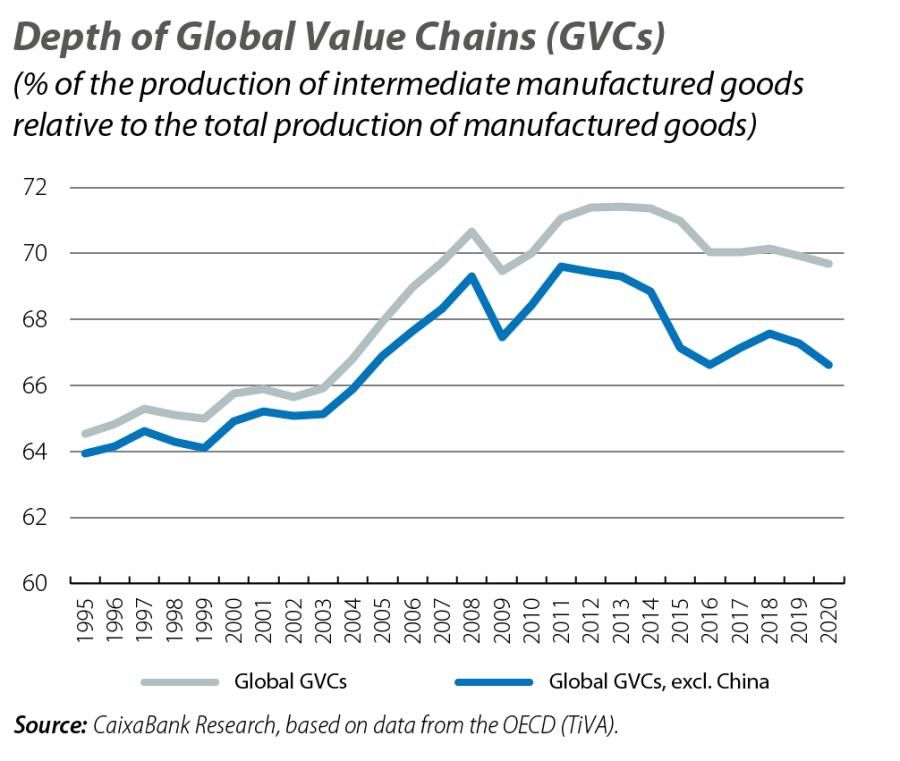

One caveat that should be taken into account when analysing global trends is that the sheer size of the Chinese and US economies can distort the global picture, so we must exercise caution when drawing conclusions about globalisation. This factor is particularly relevant in the case of China and GVCs, given the country’s dominant role in global manufacturing production: China produced 35.4% of the world’s manufactured goods in 2020 (the latest year with available data), a figure equivalent to the production of the next nine countries combined (namely the US, Japan, Germany, India, South Korea, Italy, France, Taiwan and Brazil).

If we look at the overall picture of GVCs, they appear to have already reached the peak of their development, but the picture they paint in terms of the fragmentation of the world economy is not so negative. However, China’s value chains remain highly complex and are increasingly domestic, meaning that the country has become more sophisticated and has turned towards its domestic market. On the other hand, the value chains of the rest of the world are becoming shorter, although rather than becoming more domestic-orientated they are undoubtedly becoming more regional in nature, based on all of the above.

The sophistication of China’s economy can be seen, for instance, in its leadership in the manufacture of electric vehicles. In 2023, China was the world’s largest exporter of electric vehicles. Coupled with its significant growth in the manufacture and export of internal-combustion-engine vehicles, this made the country the world’s leading vehicle exporter in 2023.4 The current context of Western geopolitical realignment makes these goods vulnerable to trade barriers, which could deepen the fragmentation of the world economy in the coming quarters.

- 4See E. Ng Shing and R. Santana (2024). Data Blog - trade data reveal changing patterns in electric vehicles market, WTO Blog.

In short, the fragmentation of the world economy is increasingly evident, although China and its relationship with the US is clearly the epicentre. Laxer financial conditions and a slightly weaker dollar in the coming quarters ought to favour global trade in goods. However, if the EU disconnects from China in a similar way to the US, this could deal an additional blow to globalisation in the form we have known it up until the last decade.