The first budget of the 27-member EU

In early 2018, the various countries of the EU and the European institutions began to negotiate the next EU budget (formally known as the multiannual financial framework, or MFF). This budget establishes the annual expenditure limits that the EU can allocate to financing common policies over a seven-year period (2021-2027).1 In this Focus, we will go over the key points on which the negotiations regarding the EU’s financial framework will focus and we will see what can be expected from it.

Although the common budget is somewhat modest - it represents 2.0% of the EU’s total public expenditure and 1.03% of the EU’s gross national income -, it is an expression of the Union’s political priorities, given that it outlines the areas in which the Member States want to dedicate their efforts over the coming years. However, it must overcome significant restrictions to ensure that the composition of the expenditure adequately reflects the EU’s vision, as well as to enable it to properly tackle the present and future challenges it faces.

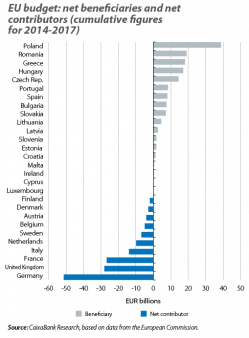

First of all, the next budget will be the first post-Brexit budget. With the departure of the United Kingdom, the EU is losing a net contributor. As shown in the first chart, under the current budgetary framework, the United Kingdom has paid approximately 28 billion euros more than it has received (representing 1.4% of its GDP),2 cumulatively between 2014 and 2017, making it the largest net contributor after Germany. Therefore, when the United Kingdom ceases to contribute to the common budget,3 starting from 2021, this will have a considerable financial impact on revenues - some estimates put the financial gap at between 10 and 12 billion euros per year, which is approximately 7.1% of the current budget.4 This funding gap could hinder the already difficult negotiations between net contributors5 and beneficiaries of the budget, given that the 27 remaining members must decide whether they want to compensate for this reduction in revenues with an increase in contributions or with a reduction in expenditure. Furthermore, in the event that they agree to increase the contributions, they will have to decide how to distribute the load.

Furthermore, this reduction in resources because of Brexit coincides with the Member States’ desire to devote more efforts to new areas that are considered priorities. In particular, the 27 remaining members recently laid out their vision for the Union for the next 10 years6 and identified areas in which they are committed to working in order to achieve it. In this regard, the global challenges that have emerged in recent years - including geopolitical conflicts, terrorism and the refugee crisis - have highlighted the importance of greater coordination and European integration on foreign policy, defence and security. To this end, the 27 remaining members want to dedicate more resources, as well as more coordination efforts, to these areas. The challenge lies in determining how to dedicate more resources to these new political priorities while at the same time continuing to allocate resources to other existing areas of the budget that remain important for the Union’s economic future, such as research and development, digital transformation and youth mobility.

In this context, and in order to fill the hole that Brexit will leave and to have sufficient resources for the priority areas of expenditure, the European Commission proposes striking a balance between cost-cutting and searching for new revenues. Although the numbers being put forward in the Commission’s proposal still have to be debated and agreed upon by all Member States, they serve as a starting point for the negotiations and provide an indication of the challenges and constraints that must be overcome. In particular, the institution proposes a very slight increase of funds from the current 1.03% to 1.14% of the EU’s gross national income - an amount that remains modest relative to the size of the EU economy. Nevertheless, some countries, such as Austria and the Netherlands, are opposed to this option and insist that, after Brexit, the size of the budget should be reduced and the remaining members should strive to make it more efficient. The Commission also proposes introducing new sources of revenues, such as environmental taxes, although some member countries have already expressed their reluctance to cede fiscal authority to Brussels. However, over the next few years, progress is likely to be made on the introduction of new sources of revenues, since following the departure of the United Kingdom, those who did not want to move in this direction will lose a staunch ally.

On the expenditure side, the Commission proposes simplifying and reorganising the expenditure commitments to focus on the aforementioned priorities, which have become more important. In addition, it proposes reducing the proportion of resources allocated to the two largest programmes, namely the Common Agricultural Policy (which consumes 39% of total expenditure)7 and the Cohesion Fund (which accounts for around 27%). However, some countries that are beneficiaries of these funds, such as Ireland and Poland, reject this strategy for fear of suffering cuts. As such, agreeing which items to cut in order to fund new initiatives could lead to a conflict of interests between the various countries and prove to be a contentious point in the negotiations.

There are also other points that could generate debate. On the one hand, the desire of the Commission and some Member States to attach conditions to the budgetary expenditure that a country receives, requiring the recipient country to respect the Union’s values and democratic principles, could accentuate the divisions between the countries of the East and West of the Union. On the other hand, the proposal put forward by France and the European Commission to devote resources (2.3% of the budget) to an institution that serves a macro-stabilising function in the euro area,8 helping the EU to cope with future shocks, is already facing opposition. In particular, the objections are coming from countries such as the Netherlands and Finland - countries that stress the importance of each country being responsible for its fiscal policy.

Therefore, in theory, the discussion on the next MFF offers an opportunity to reform the European finances and to emphasise the principle that the pooling of resources at a European level can add value in some areas and produce results that the expenditure of individual countries alone cannot. However, in order for the composition of the expenditure to adequately reflect the Union’s political priorities, major changes are needed in the allocation of common resources, and countries must stop focusing on the net balances - the difference between what countries contribute and receive. The outcome of the negotiations on the next financial framework will reflect the true commitment of the remaining 27 members to firmly proceed with the building of the Union. In this regard, despite the continuing manifestations from Europe’s main political leaders to move forward with the European project, and the desire to focus on areas that are considered priorities, it will be difficult to change the dynamics that have guided the negotiations of previous budgets. The risk, in short, is that the Member States could end up adopting a budget that is very similar to the previous ones.

1. Although the current financial framework does not end until the end of 2020, discussions must begin well in advance. This is because the negotiation process is usually complicated and drawn out, as it involves discussion on both the financial aspects and the common priorities for the next few years, and also because the budget must be approved by both the European Parliament and the European Council (unanimously).

2. In real terms.

3. Although the United Kingdom will formally leave the EU in March 2019, in the negotiations on the departure agreement, in which the divorce terms have been agreed, the United Kingdom has committed to meeting its financial obligations until 2020, when the current budgetary framework comes to an end.

4. Besides the revenues, we must also take into account the EU’s expenditure in the United Kingdom and the rebate of a portion of the United Kingdom’s contributions to the budget that the EU repays it. In addition, any payments that the United Kingdom makes after Brexit, in exchange for taking part in specific programmes, must also be taken into consideration.

5. Each country’s contribution is divided into three parts: a fixed percentage of its gross national income (GNI), tariffs collected on behalf of the EU and a percentage of the VAT revenues that countries collect.

6. In particular, the Bratislava Declaration (in September 2016), and later in the Rome Declaration (in March 2017), the remaining 27 members set themselves the goal of achieving a Europe that is safer and better protected, more prosperous and sustainable, more social, and one that has a greater presence on the global scene.

7. Data from the European Commission for 2017.

8. As well as in those countries participating in the European exchange rate mechanism (currently, only Denmark).