On the normalisation of monetary policy

The COVID-19 crisis has been a shock on a global scale, but its economic impact has been quite uneven from country to country, reflecting differences in productive structures and public policy response. Given this asymmetry, it is no surprise that the recovery is also occurring at very different paces, exacerbated by the discriminatory access to the vaccines and the continuous new outbreaks of the virus.

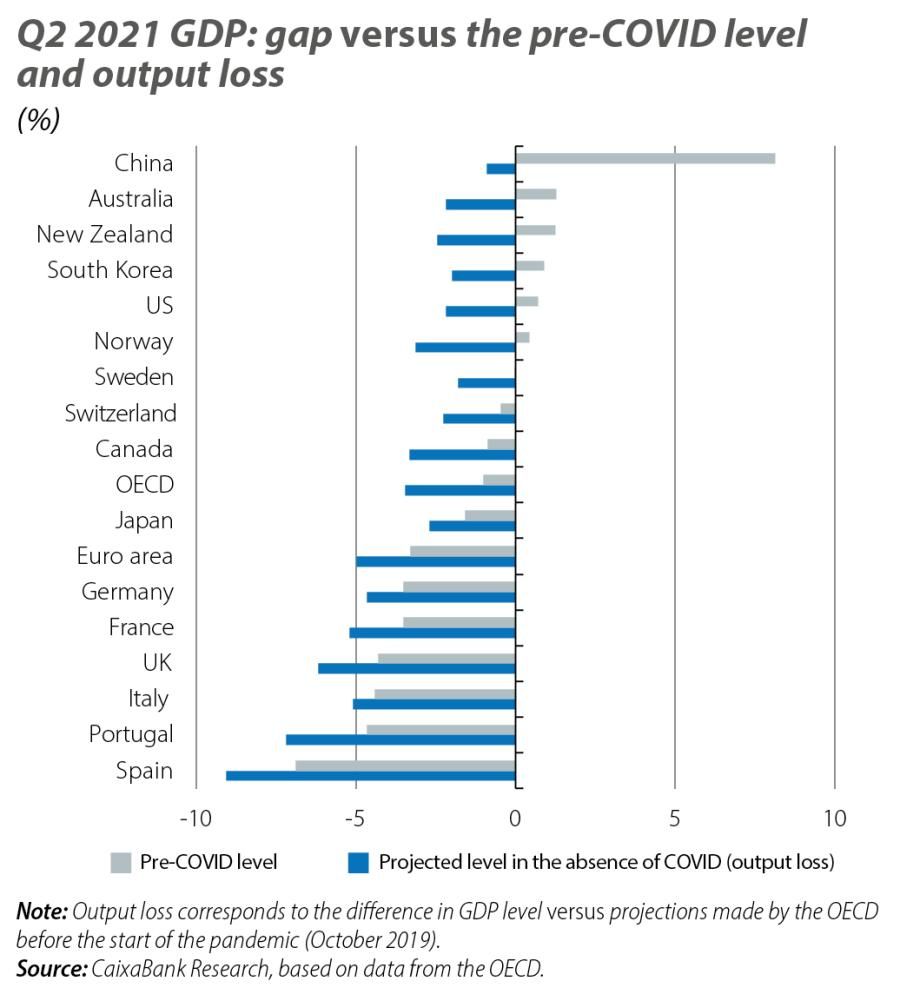

Thus, as of the end of Q2 2021, only a handful of countries have managed to recover pre-pandemic levels of economic activity. Among advanced economies, we highlight the US, with its GDP already 0.9% above the level of Q4 2019. In the case of China, meanwhile, its ability to rapidly bring the health emergency under control allowed it to register positive growth even in 2020. Yet even in China, GDP has not yet managed to recover to the level it would have reached in the absence of the virus. In fact, viewed from this angle, referred to as output loss, no country shows a positive balance, as illustrated in the first chart.1

- 1Output loss corresponds to the difference between the observed level of GDP in Q2 2021 versus the level which was projected for that period at the end of 2019, taking OECD forecasts.

Monetary policy, at a turning point

As the vaccination campaign progresses, the economic recovery is leading to a shift in monetary policy. In developed countries, there is no longer talk of new stimulus, but rather of when to start the eventual withdrawal.2 In the case of emerging countries, meanwhile, some have already raised their official interest rates.

Indeed, like the economic recovery itself, this normalisation process is taking place unevenly from country to country, due to various factors. Firstly, there are differences in the current state of the economic recovery and its future outlook in each country, as illustrated in the second chart. The needs for monetary stimulus appear to be less urgent in the US, for instance, where the economy is projected to reach its potential by the end of this year. In contrast, in the euro area the economic cycle is lagging behind (the output gap is expected to remain in negative territory until the end of 2022), so there is less pressure on the ECB to begin the withdrawal.

- 2The strategy seeks to bring net asset purchases to an end, in the first instance, and subsequently to raise official rates.

A second factor is the persistence of inflationary pressures during the reopening process, partly as a result of the factor mentioned above, but also because of the temporary imbalances between demand and supply (accentuated by savings accumulated during the pandemic and exposure to bottlenecks in global production chains). The US also stands out in this sphere, as the country’s inflation has reached more than double its central bank’s target rate.

Finally, there are idiosyncratic imbalances, ranging from the risk of bubbles in certain sectors, such as real estate,3 to other macroeconomic imbalances which alter the external position. The latter factor mainly affects emerging economies, which have seen their currencies depreciate against the dollar in the year to date, as the financial markets incorporate expectations of reduced monetary stimulus in advanced countries. To minimise the risks associated with this adjustment (which could materialise as a negative external liquidity shock),4 some central banks have already begun to raise official interest rates (such as those in Russia, Mexico, Brazil and Hungary, among others).

- 3Housing prices have risen significantly in most advanced countries. However, the risk associated with such a rebound does not affect all the central banks’ reaction function to the same extent: it is more relevant in the Nordic countries, such as Norway or Sweden, as well as in Australia and New Zealand, where it was recently included in the central banks’ mandate. In the euro area, it is expected to gain importance in the ECB’s decision-making as a result of the strategic review.

- 4See the Focus «Emerging economy outlook: an uneven recovery» in the MR05/2021.

Our outlook for the advanced economies

With these elements, we can classify the central banks of developed countries into three groups.

In the first group, we have the countries that are furthest ahead in the business cycle and/or those which show clear signs of acceleration in the real estate market: New Zealand, Norway, Australia and Canada. Their central banks are expected to kick-start the monetary normalisation process this year; they have all reduced the rate of asset purchases already, and rate hikes are anticipated in New Zealand and Norway (the first hike was announced in September).

In the second group we have the US and the UK, countries which have seen a strong rebound in the economy in the first half of 2021, thanks to a rapid vaccination roll-out, and which have also recorded significant inflation rebounds, even if the driving factors are transitory in nature. In the US, we would expect these factors to lead to a less expansionary monetary policy. However, the implementation of the Fed’s new strategic framework, focusing on an inclusive recovery towards full employment and anchoring inflation expectations, has paved the way for a very gradual withdrawal strategy. In any case, we believe that further progress in the labour market will allow the Fed to begin to reduce its net asset purchases in the coming months and to begin to raise interest rates in 2023. In the United Kingdom, the Bank of England will end net asset purchases this year, with official rates potentially being raised at the beginning of 2023 or even earlier (the markets anticipate the first rate hike in the first half of 2022).

Finally, in the third group we place the euro area and Japan, economies that are lagging behind in the recovery process. For the ECB, we expect net asset purchases to continue until at least 2023, with the first rate hike not expected until late 2024. In Japan, we expect both the yield curve control policy and official rates to remain unchanged for the foreseeable future.

In any case, regardless of which group a given economy is in, all of them will test the resilience of the global recovery and will be exposed to the risks that are inherent to the normalisation of monetary policy, in a context which remains highly uncertain and still tied to the evolution of the pandemic. Indeed, the package of measures put in place by the monetary authorities has been a key factor in preventing the health crisis from becoming a financial crisis up until now. Whether this remains the case will largely depend on the strategy that is adopted by the central banks in their transition towards the «new normal».