Mario Draghi and his «parole, parole»

The European Central Bank (ECB) has not altered interest rates since 16 March 2016 but that does not mean it has kept itsmonetary policy stance unchanged. The most prominent instrument employed in the past few years is the ECB’s asset purchase programme (QE), which has been repeatedly altered both in terms of duration and size. But there is another tool, ostensibly more anodyne and less technically inclined, that might be even more effective: words.

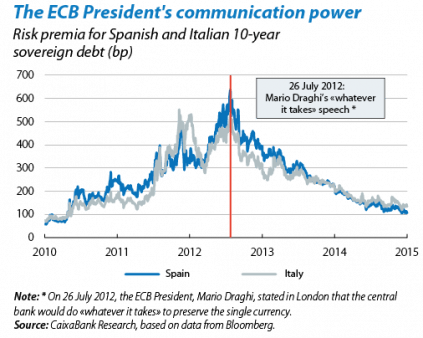

The power inherent in the communication carried out by central banks is well illustrated in the first chart. On 24 July 2012, the euro area’s peripheral risk premium reached 605 bp, an all-time high, amid rising concerns on the survival of the euro. Two days later, the ECB President, Mario Draghi, put an end to these fears with a simple sentence: «Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough». From that moment on, risk premia started to fall sharply and Draghi’s words went down in monetary policy history as the «whatever it takes» speech.

Communication is powerful because monetary policy is not only passed on via its configuration at the time but also through investors’ and savers’ expectations of its future configuration. Central banks used to neglect this second mechanism. For instance, before 1994 the Fed provided no information on the decisions taken at its meetings; investors had to infer these by observing the daily transactions carried out by the Fed itself. However, as we can see in the second chart, since the end of the 1990s communication has been increasingly used, not only in public speeches but also by publishing economic forecasts, highly influential among analysts and investors, and academic articles, which also play a part in constructing the narrative (and are particularly important in uncertain times such as the past few years). Inflation targeting also forms part of communication insofar as, since these targets are public, they help to predict how monetary policy will react to different events.

Another macroeconomic element has also emerged over the past few years related to the effects of monetary policy. After reducing benchmark interest rates (typically short-term) to levels close to 0%, central banks have continued to influence medium and long-term interest rates (more relevant for saving and investment decisions) through «forward guidance»; i.e. the probable course of monetary policy. For example, the ECB has stated that it expects to keep interest rates unchanged for a long period of time.

In view of the increasing use of communication, several studies examining its costs and benefits have concluded that, in general, central banks have achieved their aims. First, this increase in communication has been associated with a better understanding, by analysts and consumers, of the theoretical basis of central bank decisions. Dräger et al. (2015)1 show that the Fed’s efforts to improve communication have resulted in a larger proportion of consumers and analysts forming expectations regarding inflation, growth and interest rates that are in line with economic theory.

Second, in addition to the effective transmission of expectations and financial asset prices, of which Draghi’s «whatever it takes» is a prime example, the evidence also suggests that communication carried out by the Fed and the ECB is a significant predictor of future monetary policy decisions and therefore reduce uncertainty regarding the path of monetary policy.2

Finally, several studies have shown that the use of communication and particularly «forward guidance» makes financial asset prices less sensitive to the macroeconomic data published.3 This indicates confidence in the central bank’s promises and also reduces financial volatility. In fact, Coenen et al. (2017)4 have shown that, since 2012, on the days when the ECB has given a press conference, financial volatility has been below the (daily) average observed between 1999 and 2011. They have also shown that there have been more episodes of reduced volatility in general.

Nevertheless, the findings by Coenen et al. (2017) depend on the complexity of the press communication. In fact, the authors have shown that more complicated press communications generate greater financial volatility. This is a particularly important point given the increase in language complexity of central banks (see the third chart), partly an inevitable consequence of the use of complicated unconventional tools such as QE. A more intensive use of communication can therefore cause episodes of higher volatility. For instance, Ehrmann and Talmi (2016)5 have analysed the case of the Bank of Canada and have shown that, after a series of very similar communications following its monetary policy meetings, the introduction of rather more substantial changes in the next communication increased financial volatility.

Another example where communication can generate volatility is when, due to hints given by a central bank, investors focus on a few economic variables but fail to analyse these in depth. An example in case is that of inflation expectations. Investors realise the ECB may react with a more accommodative monetary stance should inflation expectations fall. Investors also know that one of the indicators used by the ECB to analyse the trend in inflation expectations is a financial instrument called an inflation swap.6 Investors therefore interpret a fall (rise) in the interest rate for such swaps as a fall (rise) in inflation expectations. However, as argued by Shin (2017),7 inflation swap interest rates are also affected by the market’s own idiosyncratic factors.8 Given that these are typically technical and difficult to measure, investors tend to ignore them, leading them to wrongly infer movements in inflation expectations. However, Shin (2017) claims that the current low interest rate environment is partly due to the incorrect interpretation of low swap interest rates, which investors attribute to low inflation expectations when –according to Shin (2017)– they are actually due to market factors.

This review of the role played by central bank communication is particularly relevant at present because the ECB’s communication has been and will continue to be of prime importance over the coming quarters. For the moment, the ECB has withdrawn some monetary stimuli without causing any commotion (with an initial announcement that it would reduce its net purchases in December 2016 and another in October 2017). Its «forward guidance» is still highly accommodative. However, with euro area growth accelerating over the past few quarters, the tone is likely to alter in the next few months. This will be the first step taken by the ECB in 2018 to prepare for the end of QE but, as suggested by most of the evidence reviewed above, how this is implemented will be critical.

1. Dräger, L. et al. (2015), «Are Survey Expectations Theory-Consistent? The Role of Central Bank Communication and News», Finance and Economics Discussion Series, Federal Reserve Board, Washington.

2. Sturm, J. and de Haan, J. (2009), «Does Central Bank Communication really Lead to better Forecasts of Policy Decisions?», CESifo Working Paper Series.

3. Praet (2017), «Communicating the complexity of unconventional monetary policy in EMU» and Blinder et al. (2017), «Necessity as the mother of invention: monetary policy after the crisis», ECB Working Papers.

4. Coenen et al. (2017), «Communication of monetary policy in unconventional times», ECB Working Paper.

5. Ehrmann, M. and Talmi, J. (2016), «Starting from a blank page? Semantic similarity in central bank communication and market volatility», ECB Working Paper.

6. These consist of a fixed interest rate being traded for a variable rate (in this case, inflation). Given that the fixed rate represents the cost of hedging against inflation, this is normally interpreted as a gauge of inflation expectations.

7. Shin, H. (2017), «Can central banks talk too much?», ECB Conference.

8. Such as a premium for inflation risk. According to Shin (2017), this premium has fallen steadily over the past few years.