The perception of the economy and its paradoxes

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, American households have been much more pessimistic than one would expect given the current state of the US economy. Why is this? Is the same thing happening in Europe?

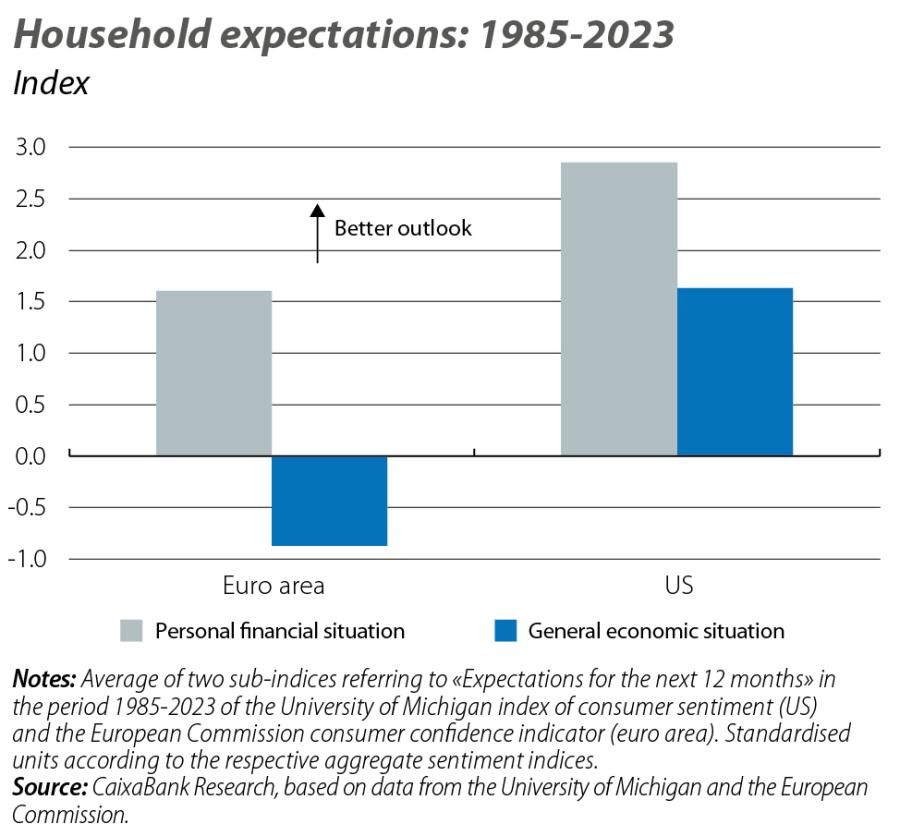

Reality and perception are inseparable, but they do not always reconcile with one another. This is also the case in economics. For example, we know that, as individuals, we systematically have a better assessment of our own personal outlook than that of the economy as a whole. This is illustrated by the first chart.

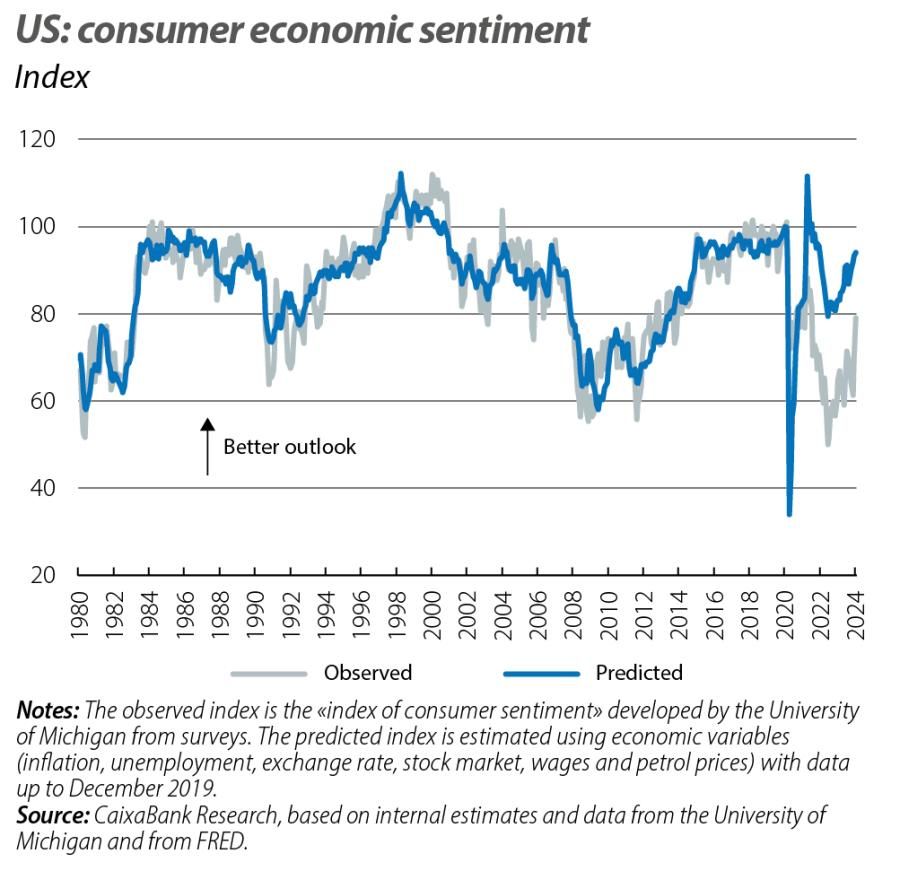

This mismatch of perceptions has taken another twist in recent years. Indeed, it seems that the close historical relationship between economic sentiment among consumers and the main variables that describe the state of the economy has been broken, and this rupture has been particularly documented in the US.1 As the second chart shows, between 1980 and 2019 just a handful of economic variables (inflation, unemployment, wages, stock market indices, etc.) were able to accurately predict the sentiment of American families. However, since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, households are much more pessimistic than one would expect given the state of the American economy. The level of pessimism is statistically excessive even given the recent inflation (one of the indicators used to predict sentiment) and especially considering the low levels of unemployment, the robust GDP growth and the fact that stock markets are at all-time highs.

This discrepancy between the economy and sentiment appears to be a persistent legacy of the pandemic, and a rather striking one at that given that the economy has long since normalised. The second chart shows a significant gap (for example, in the last three months, household sentiment is 25% lower than what the state of the economy would suggest) and, as we will see below, it is one without a definitive explanation.2 Firstly, the gap remains significant when analysing alternative measures of sentiment, such as the Conference Board Consumer Confidence Index (with a gap of 15%, despite the fact that this indicator registered a relatively moderate fall after the pandemic and that, in principle, it assigns greater weight to the performance of the labour market), and even if we distinguish between people’s perceptions of their personal financial situation and that of the general economy (both have similar gaps).

- 11. See «The pandemic has broken a closely followed survey of sentiment», The Economist (7 September 2023) and Bolhuis, et al. (2024). «The Cost of Money is Part of the Cost of Living: New Evidence on the Consumer Sentiment Anomaly», National Bureau of Economic Research.

- 2The gap is not a statistical artifice. The statistical model is estimated using data between 1980 and 2019, so to an extent it is natural that there is a good fit in that period. However, if we estimate the relationship between sentiment and economic indicators only in the period 1980-1990 and then project the sentiment that is predicted «by the economy», there is still a very close fit up until 2019.

A second possibility is that households’ sensitivity to economic indicators has changed. For example, it could be that when interest rates and inflation are high, they are more relevant to household sentiment. In fact, Larry Summers and co-authors3 show that incorporating interest rates into the analysis helps to partially bridge the gap.4 Moreover, if we estimate the relationship between sentiment and the economy in the periods 1980-2019 and 2020-2023 separately, we find indications of a change in sensitivity on the part of households: following the pandemic, good labour market and stock market performance appears to have a less positive impact on household sentiment, while the same inflation rate also seems to have a more negative impact in 2020-2023 (although, in this case, the differences in sensitivity between the two periods are fairly small).

A third explanation for the statistically excessive pessimism of households can be found in cognitive biases. On the one hand, surveys show that citizens give highly deviated answers when asked about the value taken by indicators such as the unemployment rate or inflation. Therefore, the excessive pessimism could reflect a deterioration of these biases: we think that inflation or unemployment are higher than they really are, and this leads us to have a worse view of the economy.5 Similarly, it has been widely documented that biases exist in media coverage of current affairs, with evidence that negative news not only receives more coverage, but also has a higher consumption rate.6

Finally, another explanation could simply be that the intensity of the economic turbulence of recent years has been such that households need more time than usual to digest it and that the normalisation of the economy will eventually be reflected in an improvement in sentiment.

- 3See Bolhouis et al. (2024), in footnote 1.

- 4But it does not eliminate it. In fact, the gap remains significant (and the ability of rates to narrow it depends on the statistical model used).

- 5According to surveys conducted by the University of Michigan, at the end of 2023 the median consumer estimated that inflation stood at around 6.5% (compared with observed rates of around 3.0%). In contrast, this misperception was much lower prior to the pandemic.

- 6See G. Lengauer, F. Esser and R. Berganza (2012). «Negativity in political news: A review of concepts, operationalizations and key findings». Journalism, 13(2), 179-202, and Robertson, Claire E. et al. «Negativity drives online news consumption». Nature Human Behaviour 7.5 (2023): 812-822.

What about Europe?

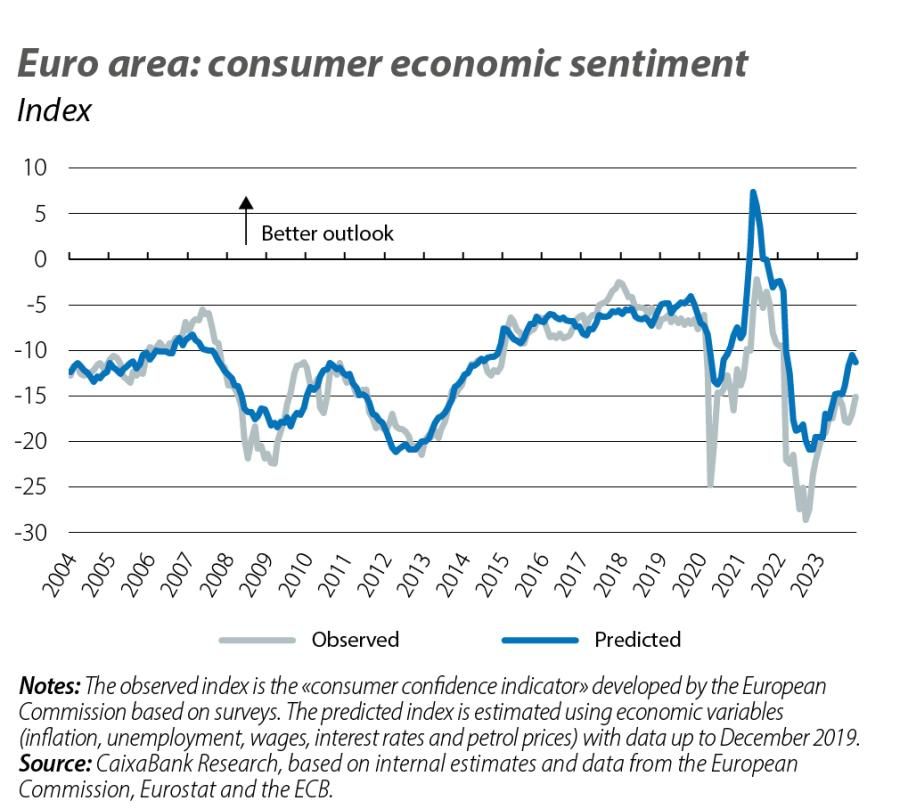

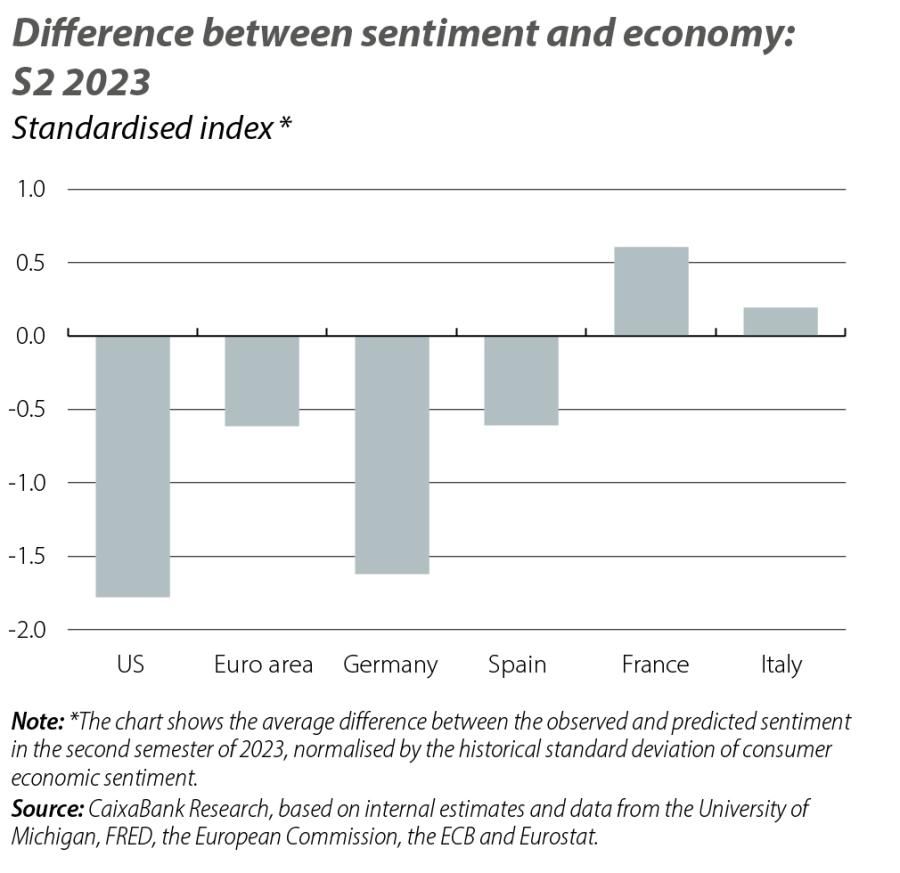

In Europe, a small set of economic indicators, similar to those in the US, has also been able to accurately reproduce the pulse of consumer confidence. As the third chart shows, a certain gap between the economy and sentiment has also opened up after the pandemic, but it is clearly narrower than in the US. Moreover, the situation varies between countries and the gap is not significant in most of the major euro area economies (see fourth chart).

The fact that the European economy, with an even more challenging economic outlook than that of the US, does not suffer so clearly from this mismatch in sentiment suggests that, perhaps, we should be looking for idiosyncratic explanations in the US. In this regard, the work of Ryan Cummings and Neale Mahoney is rather revealing.7 They show that 30% of the sentiment gap in the US reflects a partisan bias: Republicans and Democrats have a better (worse) assessment of the economy when their party is in power (in opposition). Moreover, this bias is not symmetrical, as Republicans’ perception of the economy deteriorates more when they are in opposition than it does for Democrats.

- 7«Asymmetric amplification and the consumer sentiment gap». Available at www.briefingbook.info.

‘It’s the economy, stupid’

Bill Clinton became US president in 1992 with the slogan It’s the economy, stupid! coined by his adviser James Carville. In 2024, the biggest election year in history according to many analysts, the (lack of) reconciliation between perceptions and indicators will result in the economy playing a more complex role in the election cycle, if that is at all possible.