China, the long road to economic dominance

Thanks to its resounding success in combating COVID-19, China expects to see its economy grow by 2.0% in this pandemic-filled year, making it the only major economy to end 2020 on a positive note. The future is not written in stone but, in 2020, China took significant steps towards resuming its previous role as the world's leading economy.

- Thanks to a resounding success in the fight against the pandemic, China expects its economy to have grown by 2.0% in 2020, making it the only major economy to end the year with positive growth. Moreover, the recovery is widespread, with strong growth in investment, consumption and the foreign sector.

- Despite these recent successes, the underlying macroeconomic imbalances persist. There is a greater awareness that these imbalances must be addressed, and the authorities are beginning to place greater emphasis on the quality of growth rather than on its quantity.

China, the so-called Middle Kingdom, was the world’s leading economy for much of the period spanning from the beginning of the Shang dynasty in around 1500 AC until the beginning of the 19th century.1 The Opium War (1842), the technological lag with respect to the West and the turbulent end to the imperial era (1911) constituted a cataclysm that lasted until the mid-20th century. However, from 1980, the situation changed. With Deng Xiaoping’s reforms towards a socialist market economy with special economic areas, China began the long march to regain its lost global economic dominance. China’s economic rise was dizzying, and the country went from representing 2.3% of the world economy in 1980 to 17.4% in 2019.2 The low starting point and such rapid changes brought about an imbalance in favour of producers and state investment vis-à-vis private consumers. These imbalances, combined with a financial system lagging behind Western standards and a debt which in 2019 reached 286% of GDP (including government, firms and households), set the stage for the Chinese economy’s vulnerability. Nevertheless, faced with the shock of the 2020 pandemic, the reality has been quite different.

The unique events of 2020 have done nothing but confirm that China is closer than one might think to restoring its economic dominance of yesteryear. One sign of this is the resounding success in the fight against the pandemic, thanks to strict mobility restrictions, contact tracing and mass testing (for example, after detecting 12 cases in Qingdao in October, 9 million people were tested in just five days). China’s success stands out even more when compared to Western powers. Out of a total of 219 countries, in mid-December only eight had fewer than China’s three deaths per million: three countries in Asia, two in Africa and three Pacific islands. Even with the doubts generated by the opacity of information coming from China, the figure is strikingly lower than the euro area’s 732, the US’ 943, Spain’s 1,039 or Italy’s 1,101.3

- 3See www.worldometer.com.

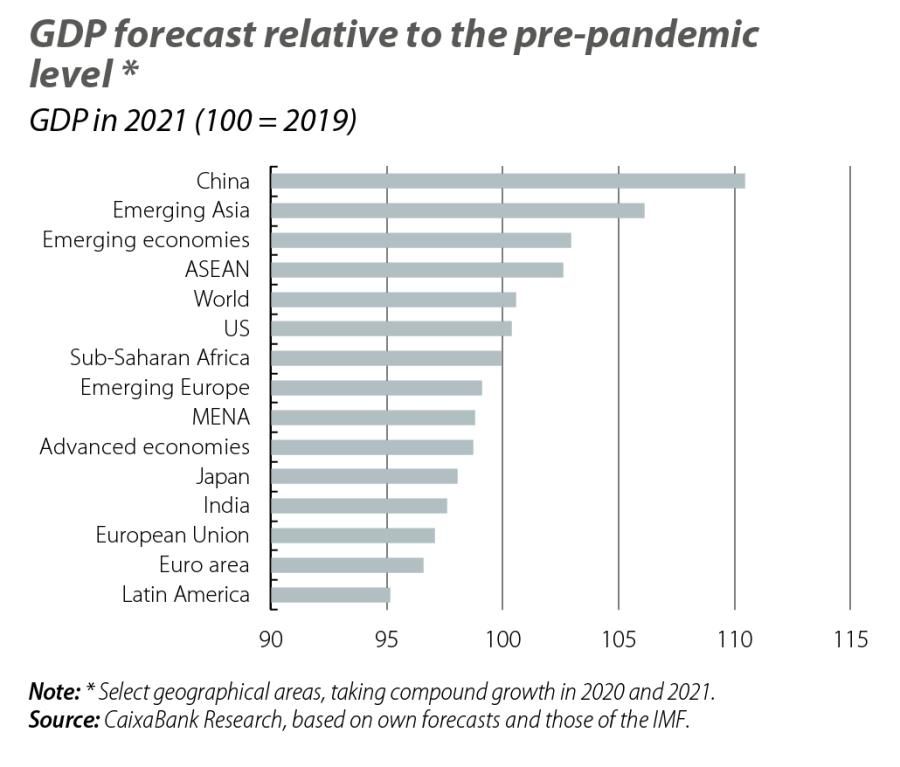

The second sign is the strong recovery of the Chinese economy, which confirms the first (the success in the fight against the pandemic), since otherwise the economic recovery would not have been possible. China expects its economy to have grown by 2.0% in 2020, making it the only major economy to end the year with positive growth. Moreover, the medium-term projections suggest that, with an expected growth of 8%, in 2021 the Chinese economy will be 10% above the pre-pandemic level. In contrast, the US will barely have recovered its pre-pandemic level, while the euro area and most advanced economies will remain between 1.5% and 3.5% below the pre-pandemic level, and the emerging-economy bloc will surpass it by only 3%. In fact, in 2020 China’s economy is already the largest in the world (accounting for more than the US’ 16%).4

- 4In purchasing power parity terms. In current dollars, China accounts for 16.8% of the global total, less than the US’ 24.4%.

The recovery that has been operating since Q2 is also widespread. On the one hand, the macroeconomic aggregates and our synthetic economic activity indicator show robust growth in investment, consumption and the foreign sector. On the other hand, the recovery is also evident in all components of our synthetic economic activity index, suggesting that economic activity maintained a growth rate of around 6% in Q4 2020.5 In this regard, while at first it appeared that the old pattern was being repeated and that the recovery was driven by state investment and industry (which is an important part of the activity indicator), at the end of the summer consumer retail sales and car sales, which also have a significant relative weight in our indicator, began to show continuous improvement, thus consolidating the recovery. This, together with a good performance from employment, makes it possible to relax the fiscal stimuli, which themselves have been less pronounced than in 2008, largely because of the debt problem. In addition, exports have grown significantly, although this should be taken in the context of a general recovery in trade flows. Furthermore, mobility has virtually recovered to pre-crisis levels, domestic air traffic is also at a similar level to before the pandemic, and restaurants and cinemas have practically returned to normal, a sign of the normalisation of social relations.

- 5We presented this index for the first time in the article «China’s economic growth under the microscope: past, present and future» in the MR02/2018.

This growth in China should help to spur on the global economy. Firstly, there is the effect that the Chinese economy has on global trade. Exports from Europe and Latin America to China have registered strong growth since June and clearly exceed 2018 levels, while exports from North America and Africa to the Asian giant remain below those levels. A second effect of China’s growth on global trade is the rise in the price of commodities, of which China is the world’s largest buyer. This will also undoubtedly have positive effects on emerging economies, which are the leading commodity producers. Thus, while all commodities declined significantly in March, in November the IMF’s non-fuel commodity price index showed a 12.5% rise compared to the level of December 2019. Similarly, copper, iron, nickel and aluminium have appreciated by 16%, 36%, 14% and 9%, respectively.

What about the imbalances of the Chinese economy? Despite these recent successes, the imbalances persist. The relative weight of consumption in GDP, with the exception of the hiatus during the pandemic, remains slightly below 40%, whilst in many advanced economies it exceeds 60%. Furthermore, independent supervision of financial institutions remains somewhat lax. Aware of this, the authorities suspended the largest local rating agency’s licence and withdrew their support for debtors with low ratings, leading to a rise in defaults and turbulence in the bond markets. On the other hand, the technological lag persists in certain areas such as semiconductors and will make it difficult for many Chinese firms to deal with the trade decoupling with the US. The difference compared to times past is that there is now an awareness that these imbalances must be addressed. Indeed, at the 19th Communist Party Congress, for the first time a greater emphasis was placed on the quality of growth rather than on its quantity, stressing the role of private consumption and high-value-added exports (the so-called «double circulation»). Furthermore, in November a package of anti-monopoly measures was announced, as was a tougher stance on low-quality debts.6

The future is not written, but in 2020 China has taken significant steps to recover its status as the world’s leading economy, as was the norm in the past.

- 6This focus on the quality of growth helps us to understand the rise in defaults observed in the corporate bond market in recent months, since this trend has been tolerated by the authorities as they resume the process of financial cleansing, now that the economy is set on the road to recovery.