Digitalise or die: the digital transformation of industries and companies

Charles Darwin's theory on the evolution of the species is based on the observation that those individuals that adapt best to the environment, rather than the strongest, have the best chances of survival. New digital technologies have radically transformed the context in which companies operate so that, applying the theory of evolution to business, it could be claimed that only those firms that adapt best to the new digital environment will survive. In this article we analyse how this digital transformation is affecting them.

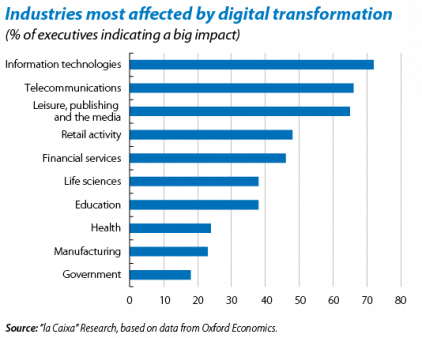

Although all companies without exception must adjust to the new environment sooner or later, it is true that digitalisation has not affected all sectors of business in the same way nor has it offered them the same opportunities (see the first graph and the article «The digital economy: the global data revolution» in this Dossier for a taxonomy of sectors according to the digital economy's degree of impact). Firstly there are the so-called «pure» or «native» sectors whose business model is designed to be carried out in a digital environment. Then there are the «revolutionised» industries such as music and the media whose business models have been displaced by the emergence of new technologies. In these sectors the internet has led to the appearance of new digital firms with totally innovative business models at the same time as revolutionising existing firms with a radical transformation in all the stages of their value chain, from production, distribution and pricing policy to consumer relations and advertising. In this respect we could say that the digital metamorphosis of these sectors is now largely complete.

More recently we have seen digitalisation spreading inexorably to the rest of the production sectors which are no longer «traditional» but gradually joining the «revolutionised» industries, an irrefutable sign that the digital economy is maturing. The disruptive effect of digital technology can be seen in an increasing number of sectors including manufacturing, agriculture, energy and health. Although it is true that digital technology does not affect the fundamental essence of these industries, adopting new technologies has become vital to continue improving their production efficiency and competitiveness. Using big data,1 cloud computing2 and social media is no longer the exclusive terrain of companies that form an intrinsic part of the digital world but even the most traditional economic sectors are taking advantage of the opportunities offered by digitalisation to increase their productivity. A study by The Boston Consulting Group3 clearly shows this: companies at the forefront of using big data generate 12% more income than those who don't use big data.

There are many applications of digital technology in traditional sectors and they have the potential to improve a large number of processes carried out by all firms. Smart factories are a case in point. These factories use big data to ensure total control of the flow of information generated in real time at production plants and points of sale (see the second graph). This information is analysed using advanced statistical techniques to improve the decisions taken at different stages in the value chain, decisions which in many cases require no human intervention but are taken automatically. One example of this is a large textile producer and distributor that adjusts the items distributed to each shop depending on the specific demand of each location, for instance by using an algorithm that predicts the sizes most sold by each store. Another innovation that has revolutionised manufacturing, as well as other sectors, is the proliferation of the «internet of things».4 The installation of sensors in machines and in various components of the product provides valuable information on the performance of different devices and downtime between processes. This helps optimise the production process in real time, reducing the need for stock and maximising production with the available resources. The challenge facing firms is to grasp the potential offered by digitalisation and they must therefore develop systems to process the growing amount of data being handled and their capacity to use these data.5

In addition to information generated in the company itself, it is increasingly important to integrate companies' information systems with those of their suppliers and clients. One critical aspect is to have a sufficiently flexible production structure to be able to quickly adapt to the changing preferences of end consumers. Within a context where value chains are increasingly more globalised and fragmented, using data on client companies (for example on their stock levels or price and promotion policy) could improve demand predictions and thereby optimise production planning, while after-sales information can also be highly valuable to design new products more in line with consumer preferences. For example, the data obtained from sensors on the use of different characteristics of a product can focus efforts on improving the most frequently used features by consumers at the same time as eliminating those least used to reduce costs.

Adopting digital technologies also entails significant organisational changes within firms. Large multinationals are becoming globally integrated organisations with specialised production units in different places in the world to take advantage of different costs, skills and access to natural resources. The advances made in information technologies and smart business help to control performance at different locations while the use of team tools and cloud computing facilitates interaction between individuals forming part of the organisation. Digitalisation also encourages organisational change towards a more flexible, decentralised model. For example, edge-based organisations are made up of many different independent units that interact directly with clients. These teams are noted for self-management, making them able to adapt quickly to changes in the environment.6

Digitalisation has also transformed how companies compete with each other. On the one hand it has notably lowered the cost of entry in many sectors and thereby increased competition. On the other hand digital technology is characterised by network externalities; i.e. the value one user gets from consuming a product or service increases with the number of users of this product or service. Under such circumstances the normal trend is towards a single network, platform or standard, resulting in «winner takes all» situations or a natural monopoly. Having a dominant position in the market, some companies have carried out certain practices that could enter into conflict with anti-trust laws. For example, the European Commission is currently investigating a case against Google for systematically favouring its own products in price comparisons on its search results pages.

In short, new digital technologies are radically transforming the environment in which companies operate, also affecting the different stages in their production and how they relate and compete with each other. Given this challenge, there is no alternative: companies must develop a strategy of digital transformation to ensure their survival and future development.

Judit Montoriol Garriga

Macroeconomics Unit, Strategic Planning and Research Department, CaixaBank

1. Big data is the term used for information systems that handle large amounts of data.

2. Cloud computing refers to the practice of transferring IT services, such as computer applications and data storage, to a remote location accessible via the internet.

3. «A Digital Disconnect in Innovation?» The Boston Consulting Group, October 2014.

4. The internet of things refers to the digital interconnection of physical objects with the internet.

5. For more information on the use of big data in other production sectors, see «Big data: the next frontier for innovation, competition and productivity», McKinsey Global Institute, May 2011.

6. See «The new digital economy: How it will transform your business» Oxford Economics, June 2011.