Exposure of the Chinese economy to a US tariff hike

While the direct impact of an increase of US tariffs on China may be limited, perhaps the greatest risk lies in the indirect effects of an escalation of protectionism: an old rule of international trade is that there is no such thing as an unanswered tariff.

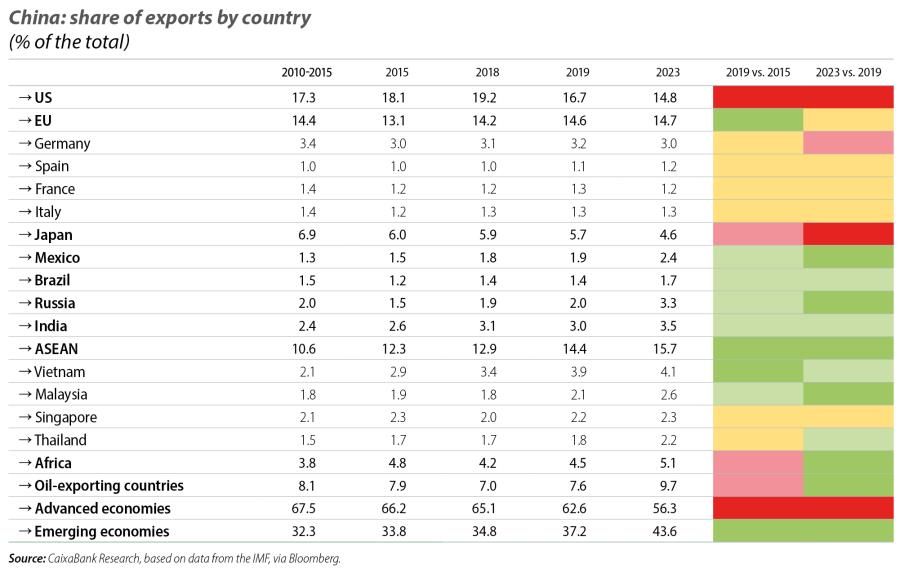

After years of trade tensions between the world’s largest exporter and largest importer, China and the US, respectively, the direct links between the two economies have been steadily decreasing. Whereas in 2018 21% of US imports came from China, by 2023 this figure had fallen to 14%.1 On the other hand, whereas exports to the US accounted for 3.5% of China’s GDP in 2018, in 2023 they represented 2.9% – a significant decline in a relatively short period of time.2

- 1In the same period, the proportion of China’s exports that are destined for the US has decreased by 5 pps, from 19% to 14%.

- 2This figure is based on exports to the US as reported by China. If we alternatively were to use imports from China as reported by the US, then the relative weight of these flows would have fallen from 3.9% to 2.4% of China’s GDP in the same period.

Exposure and sensitivity to tariffs

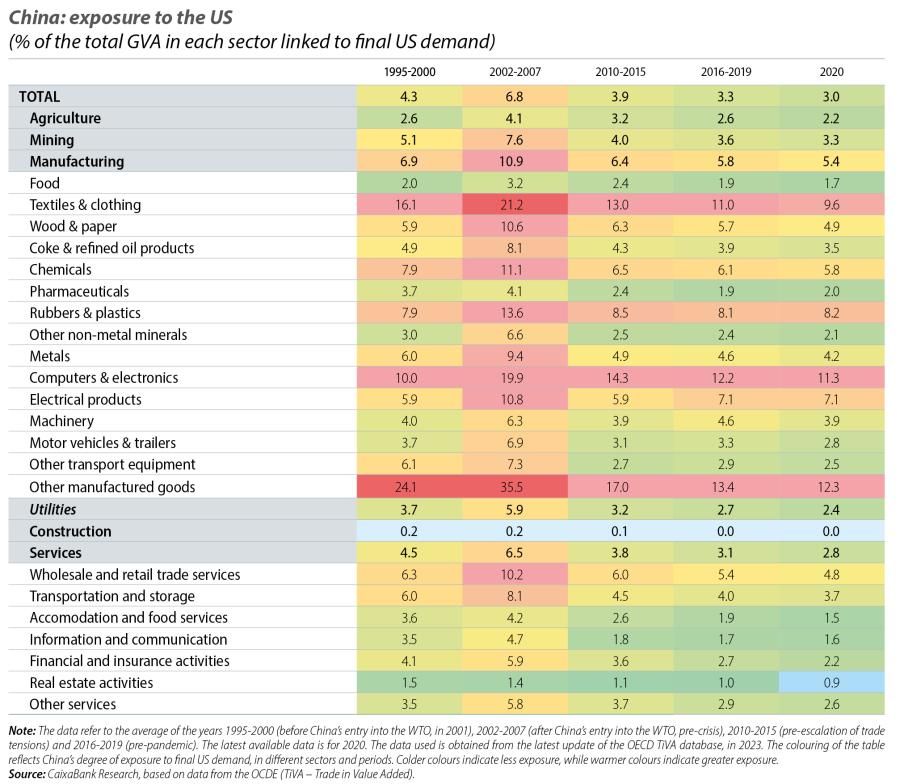

As the «world’s factory», China plays a key role in Asian and global value chains. In order to quantify this role and understand the country’s exposure to an escalation in protectionism, we must go beyond the aggregate foreign trade figures and use a different measure of exposure, namely the proportion of gross value added (GVA) originating in China that is linked to final US demand. Around 3% of the GVA originating in China ends up in the US,3 a figure that includes re-exports of intermediate goods that are produced in China, incorporated into the production of a good or service somewhere along global value chains and then re-exported to the US. This figure also includes all services exported to the US, either directly or indirectly, that are linked to goods with a final destination in the US.

- 3For 2019 and 2020, the latest years available. The average for the period 2016-2019 was 3.3%, while at the beginning of the decade it was around 4%.

By sector, on the goods side, the aggregate exposure of the manufacturing sector stands out: between 5% and 6% of the value added of China’s manufacturing sector has the US as its final destination. This is lower than the EU’s manufacturing sector’s exposure to the US (7%), but it has greater repercussions for the Chinese economy as a whole, as manufacturing accounts for 30% of the total value added in China, compared to 17% in the EU. Within the manufacturing sector, there are particularly strong links in electronics, textiles, rubbers and plastics, electrical products and chemicals, sectors where China is highly specialised and which account for around one third of the value added in the country’s manufacturing sector as a whole. Among services, the exposure is also significant (around 3% of the sector’s value added is linked to US demand) and it is particularly concentrated in services «linked» to the export of goods, such as trade and logistics services.

Based on these figures for trade exposure, if we assume that the introduction of a 60% tariff on US imports coming from China (versus a current average tariff of around 15%) would result in a one-third decline in the US’ final demand for Chinese products,4 then the impact on China’s GDP would be around 1%. However, these figures probably overestimate the impact of the US imposing a unilateral tariff. The first reason for this is that, a priori, such tariffs would be imposed on goods and, on the other hand, the exposure figures mentioned above include all exports of the services sector (whether direct or indirect). If we consider only the effect on exports (direct or indirect) of goods, plus the knock-on effect on the services sector, a more accurate approximation of China’s aggregate exposure to US demand can be obtained using the value added originating in China that is incorporated into the US’ imports of goods (from any country). For 2019, this figure is 2.6%. Using this measure, the aggregate impact in terms of GDP would be reduced by 0.1 and 0.2 percentage points (to 0.8%-0.9% of GDP).5

In a scenario with the US introducing differential tariffs (the announcements made during the presidential campaign point to the introduction of a universal tariff of 10% and a bilateral tariff of 60% on China), there is likely to be a redirection of exports from China. This could occur either due to a strategic decision taken by companies with production in China in order to «dodge» the tariffs and maintain their export flows to the US (which would represent a «pure» rerouting of trade flows) or as a result of actual devitations of trade flows. In the latter case, this would lead to higher exports of final and intermediate goods to other countries and a decoupling between the world’s two largest economies.6

In this regard, it should be noted that in recent years there has been a rapid transformation of China’s export destinations. Whereas in 2015 66% of China’s exports went to advanced economies, by 2023 this figure had fallen by 10 pps. Thus, in 2023, 44% of China’s exports reached emerging economies. Particularly noteworthy is the increase in the proportion of exports going to emerging Asian countries (a 4-pp increase between 2015 and 2023), which mostly occurred during the first phase of the escalation of trade tensions between 2015 and 2019, and the increase in the relative weight of exports to Mexico, India, Russia and oil-exporting countries since 2019, in a period when the existing trade tensions were exacerbated by geopolitical tensions. Also of note is the stability of trade flows between China and the EU, at a time when the share of the country’s export of goods going to the US and Japan was rapidly declining.

- 4This would imply a price elasticity of China’s exports to the US of around 0.7, which is in line with recent evidence (S. Devarajan, D. Go and S. Robinson [2023], «Trade Elasticities in Aggregate Models - Estimates for 191 Countries», Policy Research Working Paper 10490, World Bank Group).

- 5Tariffs can cover only direct exports of goods or they can include so-called «rules of origin», in which case they also affect indirect exports. This is a technically more complex option and poses a bigger administrative challenges. The trade exposure measures used in this Focus include both types, as they incorporate intermediate goods and services that are produced in China and then incorporated into exports of goods of third countries to the US. While this could result in an overestimate of the aggregate impact of a tariff that is only applied to direct exports, it has the benefit of taking into consideration the knock-on effect on other trade flows. Moreover, in a context of uncertainty over trade policies and the introduction of a universal tariff on US imports of goods, which would have an additional impact on China by causing a reduction in global demand, it can be considered a reasonable approximation.

- 6

For further details on the recent evolution of trade flows between China, the US and the EU, see the Focus «Is there «early» evidence of de-risking?» (parts I and II), in the MR01/2024. Moreover, imposing a 60% tariff on imports of goods from China would lead to a depreciation of the yuan, which could partially absorb the increased price of goods caused by the US tariff. It is also possible that US producers could absorb part of the rise in import costs. On the other hand, the net impact on the effective exchange rate is relevant: if China’s exports were to gain greater price competitiveness, then this could even provide a boost to China’s exports to other countries.

Protectionist risks in a fragmented world

In an environment of greater trade fragmentation between China and the US, and a significant increase in the relative weight of emerging economies as a destination for China’s exports of goods – partly to countries such as Vietnam or Mexico, which could be considered «connector» countries, but also to major economies of the Global South, which offer large alternative markets for the goods and services produced in China – we can expect China to be more prepared, with better established alternative trade routes and greater ability to mitigate the impact of an increase in US tariffs. At the same time, the scope for additional deviations of trade flows may be more limited, while so-called connector countries could be targeted in the event of a protectionist escalation, making them both potential winners but also more vulnerable.

While the direct impact of an increase of US tariffs on China may be limited, perhaps the greatest risk lies with the indirect effects of an escalation of protectionism. If «tariff» appears to be the US president-elect’s favourite word, an old rule of international trade is that there is no such thing as a tariff without response. The final impact on (i.e. the destruction of) value added will largely depend on the diplomatic channels that can manage to avoid these scenarios.