Fiscal sustainability and corporate taxation under the spotlight

The high level of public debt will be one of the macroeconomic imbalances that we will inherit from the COVID-19 crisis. Solving it will require sustained economic growth and the redesign of certain fiscal policies.

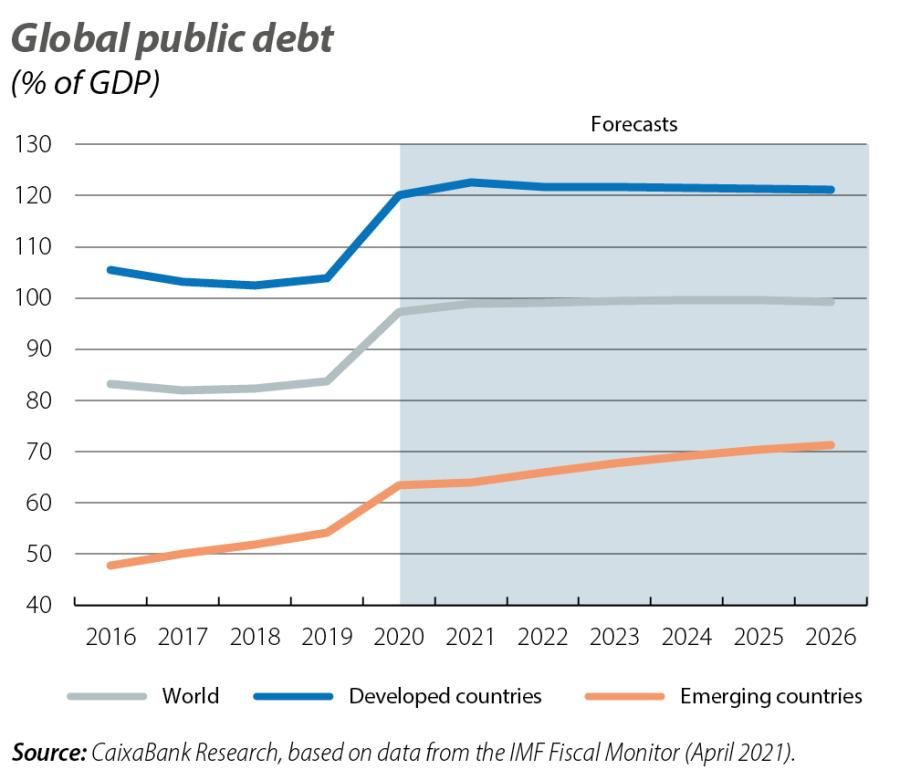

The pandemic has taken a toll on the public finances of most countries around the world. According to IMF estimates, fiscal measures to the tune of 16 trillion dollars have been introduced since the beginning of the crisis. The fiscal support has tripled the size of the global public deficit, raising it to around 11% of GDP (as of the end of 2020). The public debt ratio, meanwhile, is now approaching 100% of GDP in the global aggregate and is expected to remain around these levels over the coming years (see first chart).

Achieving a substantial reduction in these high levels of public debt, will require, at the minimum, higher economic growth rates.1 Many countries have thus begun to steer their economic policy in order to promote structural changes as well as to boost competitiveness, and therefore potential growth, in the medium and long term. The recovery fund implemented by the EU, known as Next Generation EU, is a prime example.

On the other hand, whilst governments are unlikely to introduce any sudden fiscal policy changes until the recovery is consolidated, there is increasing debate in many countries and international institutions regarding the need to rebalance the public finances.2 In the face of the difficulties governments are experiencing in reining in their public spending (indeed, the health emergency and underlying trends such as population ageing are pressuring them to do the opposite), the proposals have focused on the income side. In particular, they have put the spotlight on raising and changing taxes on high earners and, above all, on companies. These policies also seek to alleviate the high levels of inequality that the pandemic may have caused and that could emerge in the future.3

In the rest of this article we will focus on the main proposals in the sphere of corporate taxes, and those affecting large multinationals in particular.

- 1. In accounting terms, higher economic growth in nominal terms is needed, exceeding the cost of debt financing.

- 2. The favourable financial conditions, which are largely thanks to measures implemented by the central banks, also render a shift in fiscal policy less urgent.

- 3. See CaixaBank’s Inequality Tracker (https://realtimeeconomics.caixabankresearch.com/), where a marked increase in inequality before public transfers can be seen. After public transfers this increase is greatly alleviated in the case of Spain.

At its spring meetings, the IMF proposed a tax on excess profits, which would temporarily be levied on companies that have not been adversely affected by the pandemic or have even greatly prospered as a result of it (such as many in the technology or pharmaceutical sectors). Exceptional measures like these were implemented in the US and the United Kingdom in the years following both world wars.4

By country, the United Kingdom has been the first to propose a gradual medium-term fiscal adjustment programme, with a strategy that maintains short-term social support but incorporates austerity policies once the pandemic has been overcome. The main tax measures proposed include an increase in the corporate tax rate from 19% to 25% from 2023, an adjustment which, according to government estimates, would boost tax revenues by around 1 pp of GDP.

In the US, the White House has proposed two ambitious new fiscal plans with infrastructure and social spending over the next 10 years (the American Jobs Plan and the American Families Plan), which it hopes to fund through tax hikes on large corporations and high earners. In the case of corporate taxes, the current administration’s main proposals include a rise in the tax rate from the current 21% to 28%. While a notable increase, this would still leave it well below the level in place prior to the cuts introduced by the Trump administration in 2017.5 Secondly, the government is suggesting increasing and modifying two taxes designed to minimise the problem of profit shifting tolow-tax territories by American multinationals.6 Finally, the plan envisages a minimum tax rate of 15% on the accounting profits (with some adjustments) of companies with more than 2 billion in profits.7

A 15% minimum tax rate is also foreseen in the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan presented by the Spanish government to the European Commission, as well as a potential increase in corporation tax, with a particular focus on the digital economy.8 In this regard, this Q2 the EU will present a proposal for the digital tax rate at the European level aimed at increasing the taxes paid by big tech firms, which could come into force in 2023.

- 4. In the sphere of high incomes, the IMF has proposed the creation of a temporary «solidarity» levy.

- 5. With the 2017 Tax and Jobs Act, the corporate tax rate was slashed from 35% to 21%.

- 6. Multinationals shift profits to subsidiaries located in countries with low corporate taxes. A common way to do this is through inflated transfer prices applied between subsidiaries on inputs and elements of intellectual property or brand, among others.

- 7. Accounting profits can differ substantially from taxable profits, which have significant deductions. The US Treasury proposes maintaining some adjustments, such as those for taxes paid abroad, and estimates that in practice this proposal would only have affected around 42 companies in recent years (particularly big tech firms).

- 8. In the case of Spain, the proposals foresee this minimum rate being applied to taxable profits.

One of the recurring themes in most of the national proposals is the difficulty in taxing large multinationals. It is estimated that these corporations avoid around 650 billion dollars in taxes each year (see second chart).9

- 9. See E. Crivelli, R.A. De Mooij and M. Keen (2015). «Base erosion, profit shifting and developing countries». IMF Working Paper. Others place the figure somewhat lower, at 500 billion dollars.

Over the past few decades, a number of bodies have submitted multiple proposals to change international tax rules, without much success. Recently, however, one of them is gaining momentum.10 This is a revised version of the initiative launched by the OECD (known as the Global Anti-Base Erosion Proposal, or GLoBE) and, like the original version, it has two main pillars. The first is a global minimum tax rate agreed at the international level, recently supported by US President Joe Biden.

A second element is the proposal to consider multinationals as joint global entities, rather than as a series of separate entities in the various countries in which they operate. Under this joint multinational view, the percentage of the profits that are attributed to each country is determined on a pro rata basis, taking into account factors such as the workforce, the amount of capital and even sales in each country. With this allocation as a starting point, countries would be free to choose what final tax rate they apply, subject to the agreed global minimum. This methodology is used in various federal states in Germany and Japan, and it is a serious proposal that has long been considered within the EU itself.11

Ultimately, the high level of public debt will be one of the macroeconomic imbalances that we will inherit from the COVID-19 crisis. Solving it will require sustained economic growth and the redesign of certain fiscal policies. For the moment, these have focused on raising the taxes collected from higher-earning individuals and companies, particularly multinationals. While taxation of the latter is unlikely to undergo radical change beyond among regions that are broadly integrated and similar, such as the EU, it could gain some momentum with the support of the world’s major economies.

- 10. This and other proposals are set out in R.A. de Mooij, M.A.D. Klemm and M.V.J. Perry (2021). «Corporate Income Taxes under Pressure: Why Reform Is Needed and How It Could Be Designed». IMF.

- 11. Part of the Business in Europe: Framework for Income Taxation (BEFIT) plan announced by the European Commission in May.