Food prices offer a respite

The food price rally has begun to slow, but the cumulative increase since 2019 is significant and expenditure on food now represents a higher percentage of Spanish households’ consumption. The decline in agricultural and energy commodity prices in the international markets relative to their peaks reached in 2022 should help to contain agricultural production costs and thus to further ease the inflationary pressures on food over the coming quarters.

Recent dynamics in food prices

Together with energy prices, food prices have been the main protagonists of the inflationary episode that began in 2021, as we emerged from the pandemic, and which intensified in 2022, with the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. In fact, food is the component of the consumer price index that has accumulated the greatest increase over the past four and a half years. In particular, food prices surged 30.7% between December 20199 and August 2024 (latest available data), over 10 pps more than energy (20.0%) and around 13 points above the headline CPI (17.9%).

- 9Although the inflationary process began in 2021, in this article we use December 2019 as the reference period, since the composition of household consumption was greatly altered by the pandemic.

Food inflation moderates…

… but the cumulative growth in prices is very substantial

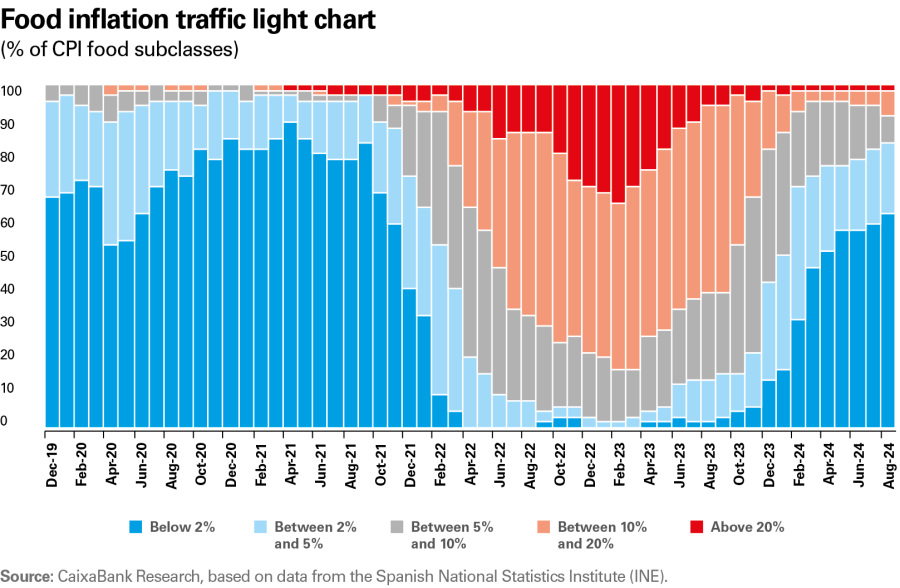

Food inflation began to pick up at the end of 2021, initially driven by the rise of a handful of products (such as vegetable oils and flours). Gradually, the price hikes became widespread across most food products, especially from 2022, when the war in Ukraine triggered a surge in agricultural production costs (both inputs and energy). At the beginning of 2023, food inflation reached over 15% (its highest rate since 1994). During that time, the price of 80% of the products in the shopping basket increased at a rate in excess of 10% year-on-year, as can be seen in the chart below. Since then, food inflation has moderated to 2.7% year-on-year in August in 2024. Inflation dynamics, however, continue to show greater dispersion than usual. In August 2024, 9.5% of food products were still recording inflation in excess of 10%10 while at the other extreme 24% of food products were recording price declines in year-on-year terms.11

- 10The six products that registered inflation above 10% in August 2024 were: olive oil (31.0%), chocolate (16.9%), fruit and vegetable juices (16.2%), potatoes (12.2%), cocoa and chocolate powder (10.7%), and sheep and goat meat (10.4%).

- 11The biggest price declines in August 2024 were recorded by other edible oils (–7.6%), pizza and quiche (–3.6%), other cereal products (–3.4%) and skimmed milk (–3.3%).

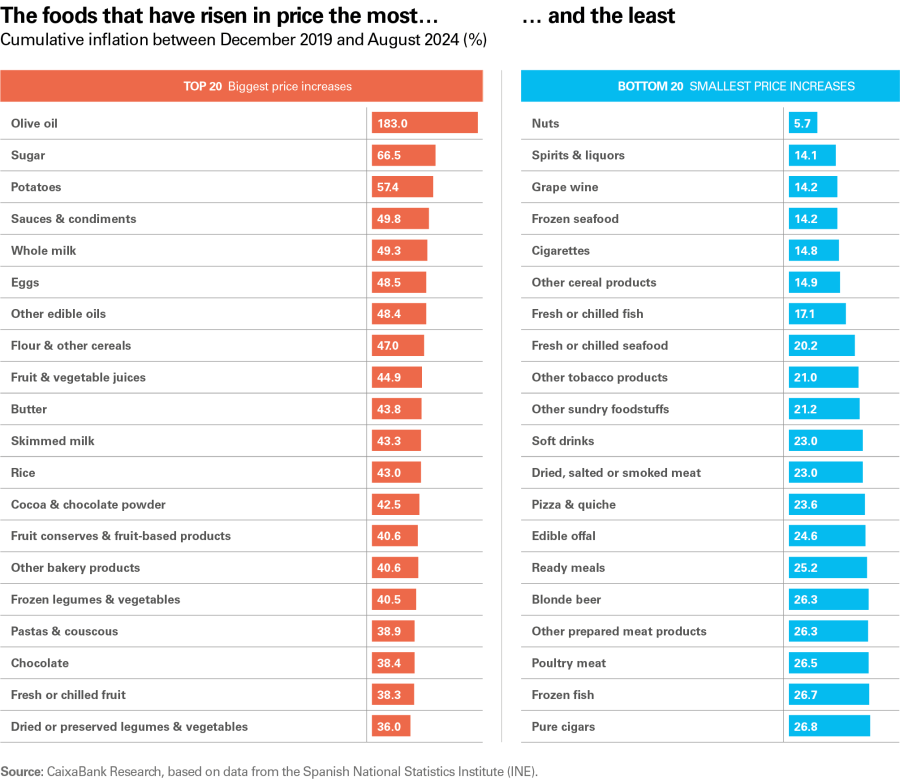

Despite moderation in food price inflation, the cumulative increase in prices between December 2019 and August 2024 is substantial. Moreover, it has been particularly pronounced in certain products that are considered essential to the average Spanish consumer, such as olive oil, fruits and vegetables, milk and eggs. On the other hand, the products that have seen a smaller increase in price include nuts, alcoholic beverages, tobacco products, seafood and fish (see table below).

At the beginning of 2023, food inflation reached over 15% (its highest rate since 1994)

One of the main determining factors behind the food price rally was the sharp rise in production costs in the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector

Recent trends in the costs incurred by Spanish producers and in agricultural commodity prices in the international markets

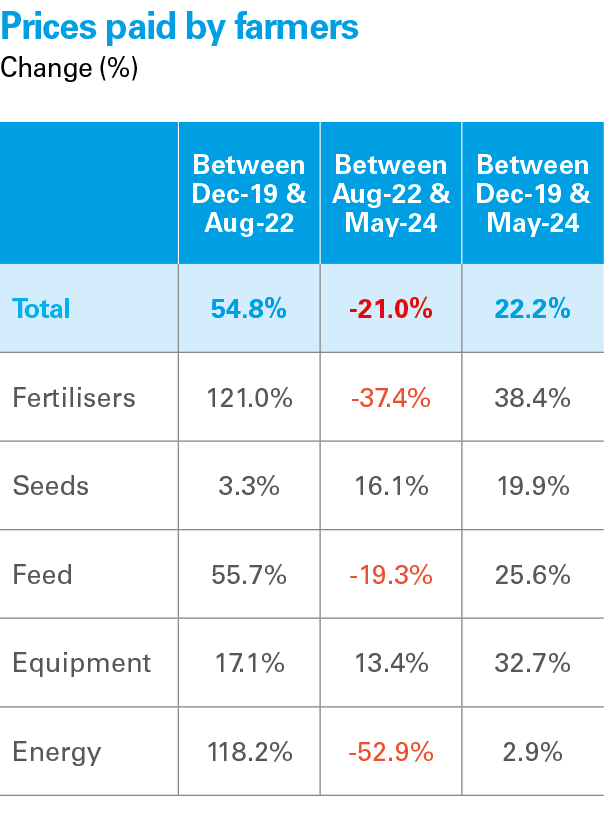

One of the main determining factors behind the food price rally was the sharp rise in production costs in the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector. According to data from the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAPA), prices paid by farmers increased by 55% between December 2019 and August 2022, mainly due to higher prices of energy (118%), fertiliser (121%) and livestock feed (56%).

Since mid-2022, intermediate costs for farmers have been moderating and are down 21% on a cumulative basis. This decline, however, has been more moderate than the previous increase, so production costs are still 22% above the pre-pandemic level.

Inflationary pressures on the first links in the food chain are easing

Looking ahead to the next few quarters, we expect this trend of moderation to consolidate. Prices of the main agricultural commodities traded in international markets have declined from their peaks of 2022, and the futures markets point to a somewhat more stable trend with prices closer to those prevailing before the outbreak of the war in Ukraine.12 In particular, futures markets anticipate that the price of wheat will be around 600 dollars per bushel in the period 2025-2027. This is slightly higher than the price in December 2019 (550 dollars) but markedly lower than the peak reached in the spring of 2022, when it exceeded 1,100 dollars. A similar trend is anticipated for the prices of corn and soybean, as can be seen in the following chart. This trend of gradual moderation in agricultural prices reflects, on the one hand, the favourable outlook for cereal supply during the 2024-2025 campaign and, on the other, the signs of a slowdown in global economic activity (in addition to the gradual deterioration of China, there are fears of a cooling of the US economy), and this is moderating the demand for agricultural commodities in the international markets.13

- 12See «Spain’s agricultural sector and its dependence on international agricultural commodity markets», published in the Agrifood Sector Report 2S 2022.

- 13The US Department of Agriculture’s «World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates» report, published in August 2024, anticipates a 0.8% increase in global cereal production, bringing the total figure to 2.83 billion tons, due to the fact that the moderation of production in the EU and the US is being offset by the excellent harvest in other global producing countries (Ukraine and Australia, among others).

Prices of the main agricultural commodities have declined and the futures markets point to a somewhat more stable trend

The transmission of production costs to food prices

The long production processes in agriculture mean that the transmission of the decrease in production costs takes months to reach final prices. In order to analyse how price increases and decreases are transmitted through the food chain to reach the final consumer, we have developed an econometric model for local projections14 which allows us to measure the intensity and duration of the transmission of production costs to the food prices paid by final consumers.

- 14The analysis in this section is based on the article «The wage-price pass-through across sectors: evidence from the euro area», M. Ampudia, M.J. Lombardi and T. Renault, European Central Bank, 2024. The model is estimated for 55 food products. The variables are expressed in terms of year-on-year difference in the logarithm of the index.

The lower prices paid by farmers are gradually filtering through the different links that make up the food chain before eventually reaching the final consumer

The following chart shows the impact which a shock in the year-on-year rate of change of the prices paid by farmers in Spain has on average food inflation. The results reveal that a temporary increase (decrease) of 1 pp in the rate of change in the prices paid by farmers results in an average rise (decrease) of 0.4 pps in food inflation after 12 months, which is when the maximum impact occurs. It is also observed that this shock is highly persistent, as the impact remains significant, albeit fading, for around 9 months after the maximum impact occurs. From this we can draw the conclusion that, if most of the upward shock in energy and input prices occurred in early 2022, then most of the impact on food inflation will now be behind us.

Moreover, given the decline in agricultural production costs already recorded, together with the recent decline in oil prices, we can expect the moderation in final food prices to continue. Therefore, over the coming months we expect the disinflationary trend in food prices to continue, although we could see a gradual rebound in 2025 once the VAT reductions applicable to certain products are eliminated. In the long term, the cumulative increase in agricultural costs puts a limit on the decline we could see in food prices.

Nevertheless, there is a great deal of uncertainty surrounding where food prices will go from here, as they are dependent on multiple factors. These include extreme weather events (not only in Spain and Europe, but throughout the world), the probability of which may increase with the arrival of La Niña, a climatic phenomenon which is characterised by an abnormal cooling of surface waters in the Pacific Ocean and can cause floods and droughts, with a significant impact on crops, especially in Latin America. Conversely, the recent decline in oil prices could also help to moderate food prices.

How has Spanish households’ spending on food changed during this inflationary episode?

The rise in food prices has had a clear impact on household food bills. As shown in the chart below, average household spending on food, which includes both consumption for the home and expenditure on catering, increased by 19.5% in nominal terms between 2019 and 2023.15 This increase is entirely explained by the price rally, since in real terms (quantity) average household spending actually decreased by 3.7%. There was also a change in the composition of food expenditure: consumption at home increased more (24.4%) than expenditure on catering (11.9%), although both fell in real terms (–3.9% and –3.4%, respectively).

The sharp rebound in food prices has resulted in an increase in the proportion of average household expenditure that is allocated to food and catering, going from 23.4% in 2019 to 26.0% in 2024. In contrast, there was a decrease in spending on other items such as transport, communications, clothing and footwear, furniture and other household items.

- 15Data from the Spanish National Statistics Institute’s Household Budget Survey.

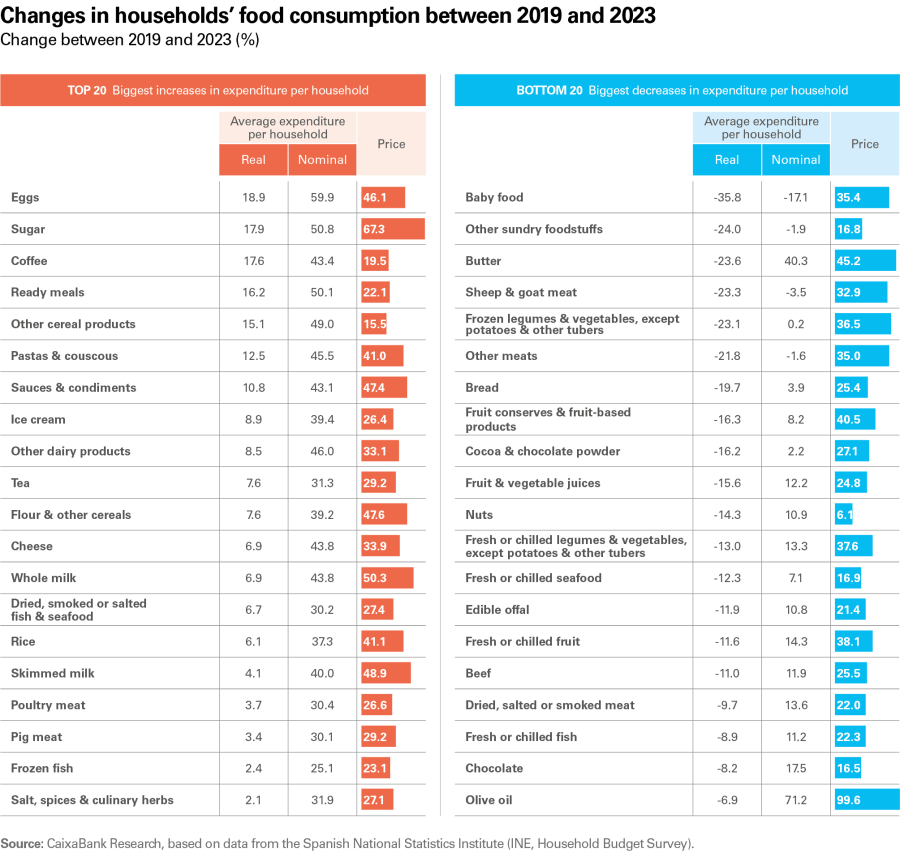

If we delve into the detail of food products consumed at home, we see that average household expenditure grew, in nominal terms, for most products as a result of the rise in prices.16 On the other hand, in real terms, expenditure has declined in more than half of all product categories. The following table shows the 20 products which have registered the greatest increase in spending in real terms between 2019 and 2023 and those on which spending has increased the least, together with the cumulative price increase during this period.

It is interesting to note that there is no direct relationship between the change in real spending and the cumulative inflation per product.17 Thus, among the products which have experienced the biggest increases in real expenditure we find essential products that have recorded bigger relative price hikes, such as eggs, sugar and pasta. However, we also find some of the products whose prices have increased the least, such as coffee and ready meals. On the contrary, consumers have reduced the proportion of their consumption allocated to goods that have become more expensive, such as olive oil and fruit, but they have also reduced their consumption of products such as nuts, which is the product category that has recorded the smallest price increase.

- 16It only fell for 8 out of the 82 products considered. Baby food (–17.1%), dietary products (–14.1%), and spirits and liquors (–6.8%) recorded the biggest decreases in average household expenditure in value terms between 2019 and 2023.

- 17The correlation between cumulative inflation and the real change in household expenditure on food products between 2019 and 2023 is 39%.

Among the products which have experienced the biggest increases in real expenditure we find essential products that have recorded bigger relative price hikes, such as eggs, sugar and pasta

In other words, despite the sharp rise in prices in some food products, their consumption has not been greatly affected, which indicates the low price elasticity of food expenditure. It is also important to note that the grouping of food products does not allow for the detection of substitute products within each subclass of products that may be of a different quality.