What is going on with Chinese consumers?

While Chinese exports have grown at a record pace since 2020, domestically the situation is different: investment remains weighed down by the crises in the real estate sector and consumption is struggling to take off. What is the reason for the weakness of consumption and the lack of consumer confidence in China?

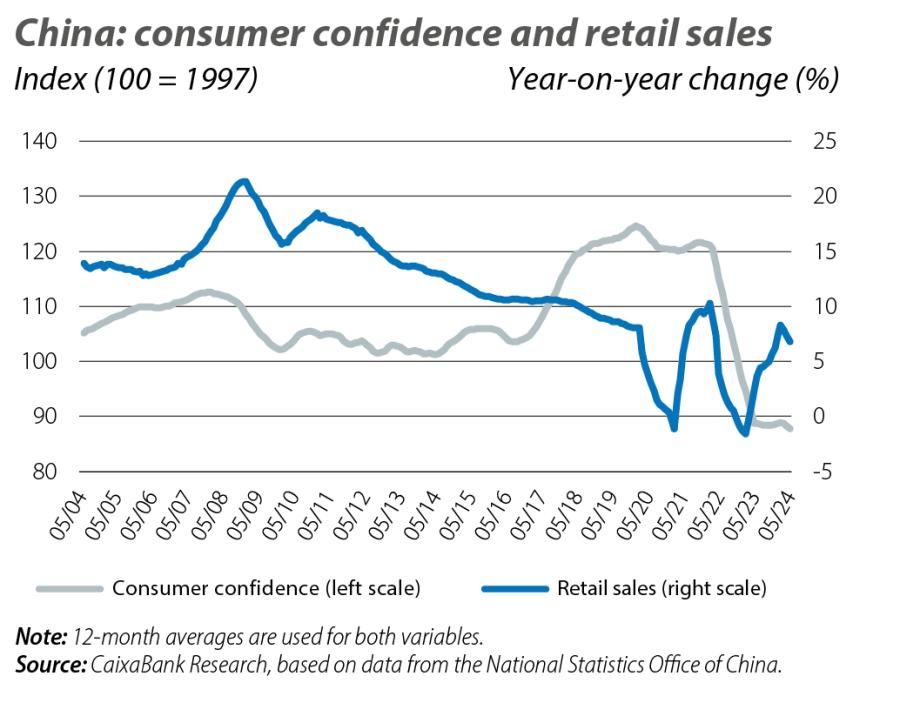

At first glance, the Chinese economy withstood the shock of the pandemic rather well. Between 2015 and 2019, it grew at an average annual rate of 6.7%, while since Q1 2023 it has sustained a growth rate of over 5%. Externally, its exports have grown at a record pace since 2020 and have gained market share, while some of its leading industries have reached a position of virtually undisputed global dominance. Domestically, however, the situation is different. Consumption has not quite taken off and investment is still weighed down by a crisis in the real estate sector that seems to have no end. In this environment, retail sales have grown by 5% in the last year (compared to a rate of around 10% in 2015-2019), while investment is growing at a rate of 4% (3% in 2023, compared to above 7% in 2015-2019). One of the most visible symptoms of this weakness in domestic demand is consumer confidence, which plummeted in early 2022 and has not recovered since. In an earlier article of this report, we saw how some economic indicators have evolved very differently from the consumer confidence indices in the US and the euro area. The differences between the evolution of such indicators can be explained by several factors, including changes in households’ sensitivity to certain economic variables, cognitive biases or idiosyncratic issues specific to each country or region.1 But what about China?

- 1See the Focus «The perception of the economy and its paradoxes», in the MR04/2024.

Lack of confidence and weak consumption: cyclical or structural?

Besides the demanding domestic economic environment, in the last two years there have also been deflationary pressures as a result of structural factors – such as population decline – and cyclical factors – namely, a real estate sector undergoing correction and the rapid expansion of productive capacity in the manufacturing sector during the pandemic, which has led to overcapacity problems. Also, the slowdown in nominal GDP perceived by consumers has been sharper than the real growth figures show, with growth slowing from around 9.0% in 2015-2019 to less than 5.0% in the last year.2

The breakdown by component of expenditure per capita also reveals some changes in Chinese households’ consumption preferences. Among the most important items, there is a sharp slowdown in spending on housing compared to in the pre-pandemic period, while spending on food has even accelerated. Also, consumption has slowed more in urban areas than it has in rural areas.3

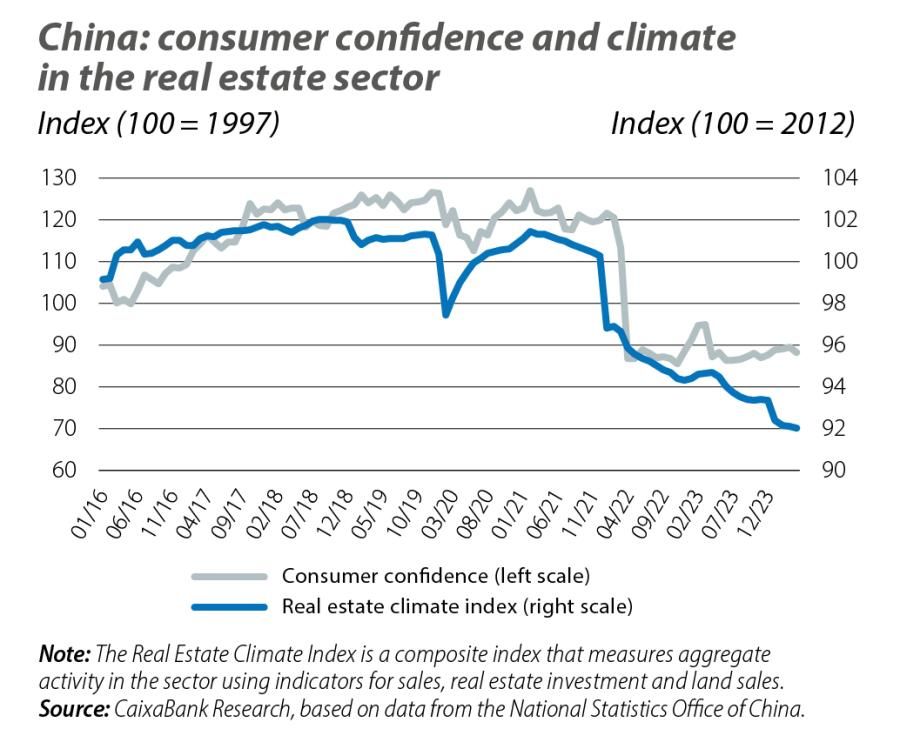

These factors, coupled with the momentum and speed of the initial decline, point to a common denominator of the lack of confidence and the recent weakness in Chinese household consumption: the real estate sector. Indeed, the collapse of consumer confidence has occurred practically in sync with the rapid deterioration of the real estate climate index (see second chart). Of course, this all occurred at a time when the country was ravaged by a new wave of infections which led to widespread lockdowns in the country’s largest cities and amplified the difficulties in the sector. Since then, the consumer confidence index has not recovered.

- 2Some recent scientific evidence also suggests that the official GDP growth estimates of some countries with autocratic regimes may be overstated. See «Shining light on lies», The Economist (1 October 2022) and L. Martínez (2022) «How much should we trust the dictator’s GDP growth estimates?», Journal of Political Economy, 130 (10), 2731-2769.

- 3On the other hand, the slowdown in the growth of disposable income was somewhat sharper in the extreme quintiles of the distribution, i.e. among the 20% with the lowest and highest incomes. In addition to the stronger negative income effect in these groups, it is reasonable to assume that the wealth effect resulting from the housing crisis is proving to be more pronounced in the upper quintiles of the income distribution. On the one hand, the sharpest price declines are occurring in Tier 1 cities (where the highest incomes are concentrated) and, on the other hand, this group tends to have a high exposure to the sector.

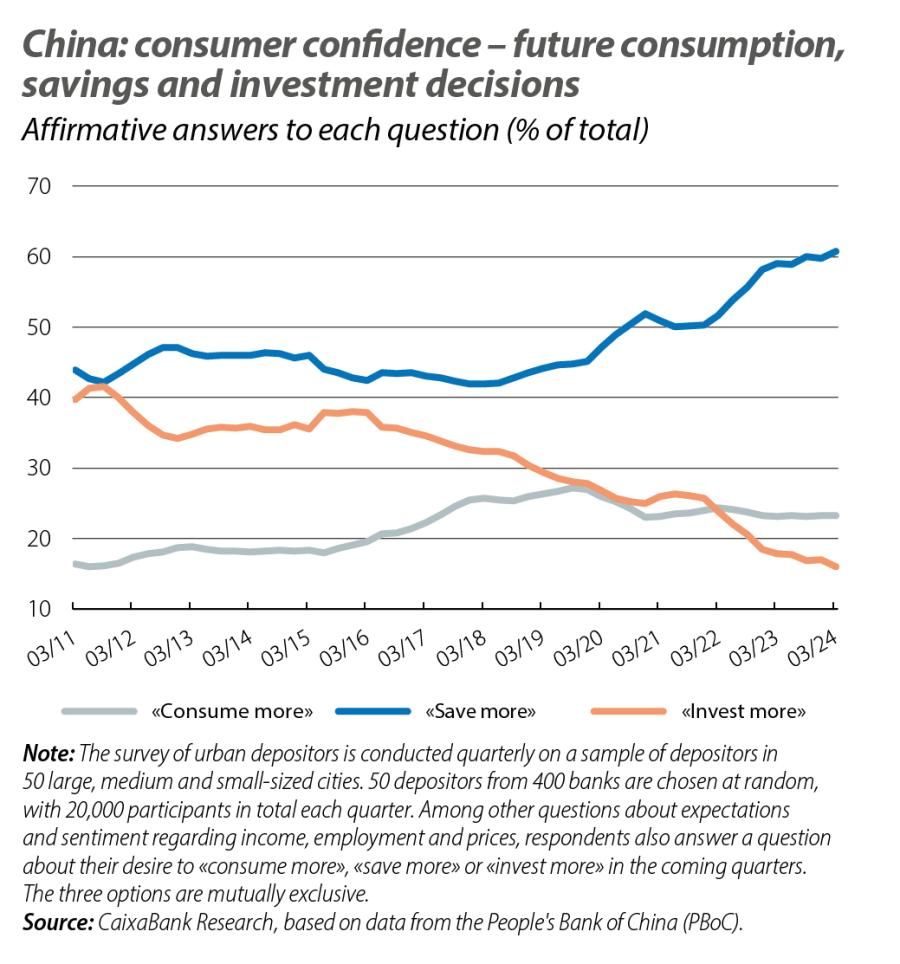

All this points to cyclical factors behind Chinese consumers’ lack of confidence – and, in a way, country – specific factors. But there are also structural factors behind the lack of consumption in China. In previous Focuses, we have explored some factors explaining the high household savings rate (and the corresponding low consumption rate) in the country.4 At close to 35%, it is much higher than in advanced economies or other economies with a similar level of development, and this trend has deepened in recent years. Since 2020, the People’s Bank of China’s quarterly depositor survey shows an upward trend in the proportion of respondents who want to save more in the future, and a downward trend in those who want to invest more. With the double shock of the pandemic and the housing crisis, Chinese households are becoming even more cautious in the face of the uncertainty about the future and the difficulty in finding attractive investment options.5

Confidence and consumption: causes and consequences

The crisis in China’s real estate sector has added a new dimension to the chronic low consumption observed in the country and now finds itself in a kind of feedback loop, being both a cause and a consequence of the lack of consumer confidence.

Besides real estate, other factors have also contributed to the deterioration in economic sentiment, such as the high rate of youth unemployment, the worsening economic environment in some sectors (such as consumer durable goods) and the perceived increase in external risks. In the short term, a sustained recovery in confidence is unlikely without underlying changes in these variables.

The Chinese authorities’ classic recipes – more investment and more exports – appear to be running out of steam in an environment marked by high debt, declining returns on infrastructure investment, overcapacity in the manufacturing sector and with the country’s global market share at its peak, all against a backdrop of growing trade tensions. Perhaps the lack of confidence can be linked to one more factor: the doubts among households that the Chinese authorities are capable of finding effective solutions to a confluence of crises in a feedback loop.

In this regard, it will be particularly interesting to follow the third plenary session this month of July at which, every five years, the Chinese Communist Party tends to discuss and announce major reforms and priorities in a variety of areas. Although the details are often slow to be revealed, it is possible that there may be a greater commitment to demand-side policies, with measures offering direct support for households, the expansion of social spending programmes or a reinforcement of measures to support the real estate sector. On the other hand, they could also point to a reinforcement of the «reforms» we have seen in recent years, with measures aimed at stimulating supply and promoting the country’s «economic security». Recently, the Chinese authorities have underlined their focus on the quality of economic growth. Will they finally be willing to bet on the strength of consumption in the world’s second largest economy?