REPowerEU or how to accelerate the energy transition to survive in the new geopolitical context

We delve into the REPowerEU plan, approved in May by the European Commission, and its measures to accelerate the energy transition envisaged in the Green Deal and the Fit for 55 package.

The war in Ukraine has marked a turning point in relations between the EU and Russia and has highlighted the serious implications of Europe’s high dependence on energy imports from Russia, especially gas. Aware that energy dependence is a handicap for the EU, in May the Commission approved the REPowerEU plan, with measures aimed at accelerating the energy transition envisaged in the Green Deal and the Fit for 55 package.1

- 1. The Green Deal is a plan presented in January 2020 with actions aimed at combating climate change and making Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. One of the first targets in the plan is to reduce emissions by at least 55% compared to 1990 levels by 2030, and this requires new standards as well as an updating of existing EU legislation, as set out in the Fit for 55 package launched in June 2022.

With the REPowerEU plan, in May the Commission presented a clear strategy to completely eliminate Europe’s dependence on Russian fossil fuels by 2027. To this end, it envisaged a specific plan to completely replace EU imports of Russian gas (155 bcm2 in 2021) by 2027, with a reduction target of two-thirds (over 100 bcm) by the end of 2022.3 However, with data up to August 2022, the EU had already imported a total of 53 bcm of Russian gas, so the reduction in dependence on Russia this year will most likely fall short of the goal set under REPowerEU. In the short term, the Commission is mostly relying on liquefied natural gas (LNG) to replace Russian gas and estimates that imports could increase this year by 50 bcm,4 a feasible target based on the available data. Brussels also hoped to replace at least a further 50 bcm in 2022 through various other means: higher gas imports via pipelines from other suppliers (primarily Norway, Algeria and Azerbaijan), coal, lower demand due to higher prices, energy savings,5 and nuclear power plants. This additional 50 bcm was a rather ambitious goal; for example, replacing 10 bcm through increased imports of natural gas from other countries, excluding LNG, will not be easy to achieve (import data for the year to date indicate that these imports have not increased). Faced with obvious difficulties in replacing Russian gas in the short term, some countries (Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and France) are considering increasing the use of coal for their electricity generation, despite the harmful consequences in terms of climate change and the fact that it contradicts the emission reduction targets set by the Commission.

- 2. Billion cubic metres. In 2019, Russian imports amounted to 195 bcm.

- 3. Although no intermediate targets between 2022 and 2027 have been set, imports of Russian gas would be gradually reduced over this five-year period until they are fully replaced in 2027.

- 4. A 60% increase over 2021.

- 5. Lowering thermostat settings in buildings by 1°C.

The REPowerEU plan reignites the implementation of many energy projects which have been pending for some time and which make greater use of cross-border connections in order to achieve an integrated market that can guarantee energy supplies in all Member States.

In the short term, the plan focuses on European projects of common interest in order to build gas infrastructures with a capacity of 20 bcm per year in Eastern Europe and the Baltic states this year, as well as supporting Germany’s plans to install seven floating LNG plants, three of which are expected to be operational this winter, joining the one which has been operational since the summer in the Netherlands. In the medium term, all European economies are expected to have access to three alternative sources of gas or to the global LNG market.

In addition, the plan envisages greater electrical interconnection between the Iberian peninsula and France through new cross-border projects. These include the laying of an underwater cable across the Bay of Biscay to connect Bilbao and Bordeaux, planned for 2025,6 as well as other planned interconnections with Navarre and Aragon. On the other hand, the possibility of establishing gas interconnections with France or Italy has also recently been raised. The plan also advocates homogenising the way gas is treated in order to enable interconnections with Central Europe (Spain and France use a different odorisation treatment process to the rest of Europe). Moreover, the plan opens the door for the peninsula to play an important role in the green hydrogen corridor: it recognises that it can take the leading role, making the most of its proximity to North Africa, although it does not provide specific details on how such a scheme would be deployed. These are major investments with a relatively long payback period, so the main risk to their development is that the pressing energy crisis could end up resulting in less money being allocated to them than is needed. The tension between the short and long term is clear.

- 6. With this 400-kilometre cable, the interconnection rate between Spain and France would reach 5%. Currently, Spain can export 2.8% of the electricity it produces to the rest of the continent, via France, but the EU advised in 2002 that cross-border connections should transport 10% of each country’s electricity production capacity.

It is apparent that, in the short term, achieving energy independence from Russia will not be such an easy task. However, one of the clear objectives of the REPowerEU plan is to accelerate the energy transition over the next eight years.

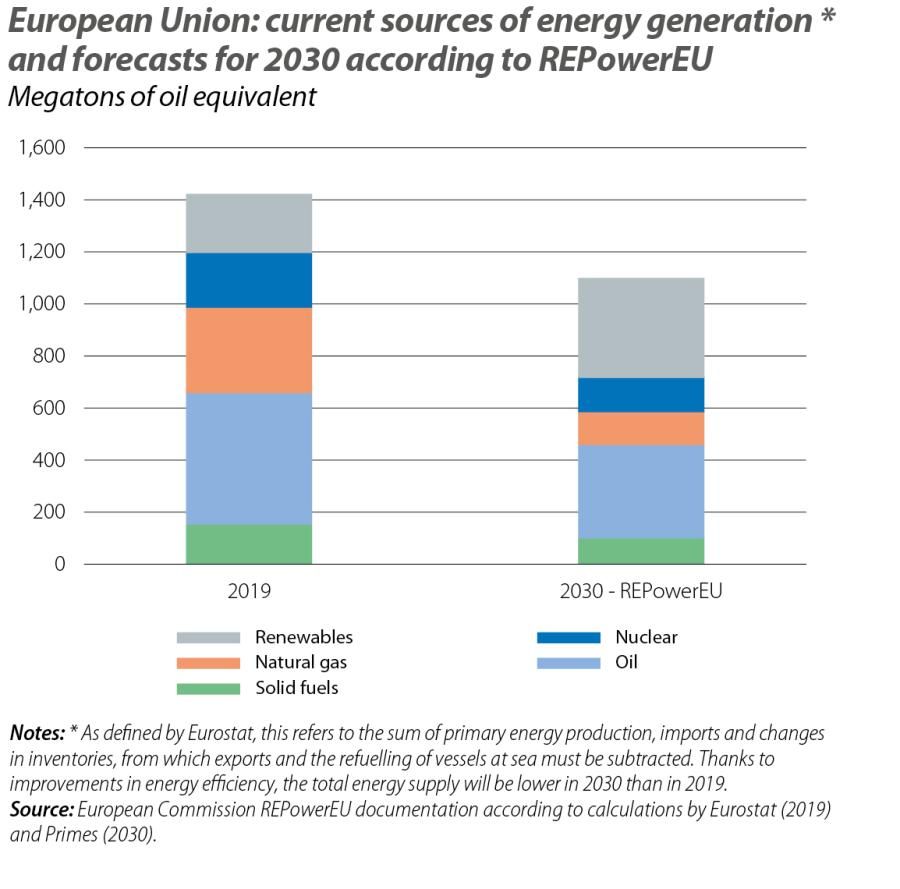

REPowerEU envisages an increased role of renewables in the EU’s energy supply by 2030. Specifically, their share of the bloc’s total energy is due to increase by 5 pps compared to the Fit for 55 energy plan, bringing it to 45% of the total, and this will come at the expense of a 7-pp reduction in gas, which will fall to 3.3% of the total. This increase is mainly based on the intention to boost renewable hydrogen and biomethane in the medium term, two renewable energies that will require significant investment in infrastructure and interconnections.

As for the installed energy capacity of renewables, the objective set under the REPowerEU plan is to increase it by 15.8% compared to the goal set in the Green Deal, primarily through a greater boost to solar energy. Thus, the total installed capacity of this energy source, which is currently enjoying a boom thanks to the significant reduction in production and installation costs, should quadruple between 2020 and 2030. In addition, the European Commission intends to speed up its deployment: it proposes cutting the time it takes to grant solar panel installation permits to three months (in some cases it currently takes up to a year), it suggests that Member States should cut VAT on solar panels and heat pumps, and it will make it easier to ensure new buildings are equipped with everything they need to produce solar energy. Thus, the Commission estimates that, under REPowerEU, within five years classical renewables (solar and wind) could replace 13.5% of the total amount of Russian gas that was imported by Europe a year before the war (155 bcm), while biomethane could replace 11%, and green hydrogen, 17.4% (within eight years in the latter case).

The REPowerEU plan will require vast investments: the Commission estimates the figure at 300 billion euros up to 2030, 210 billion of which will be between now and 2027, half of which would go to renewables. The new investments under the REPowerEU plan will come in addition to those already proposed in the recovery plans and will largely be financed via the loans which Member States have access to under the NGEU framework. Specifically, the Commission expects 225 billion euros to be financed through NGEU loans. The other 75 billion needed to cover the 300-billion total investment will be funded through grants from the cohesion funds (around 27 billion), new NGEU subsidies obtained from the sale of carbon emissions allowances under the EU emissions trading scheme (around 20 billion) and from the common agricultural policy (around 7.5 billion). At this point, it should be noted that the Commission is merely playing the role of coordinator in these energy policies, while the plan’s true success will largely depend on the will of Member States.

The banking sector can play a crucial role in mobilising funds in order to achieve the goals of REPowerEU. It can help customers to recognise this opportunity and facilitate the financing of projects in the different areas covered by the plan as well as initiatives in adjacent sectors, thus helping to ensure the funds reach the entire productive fabric of the economy and all regions.

In short, the intention is to link REPowerEU closely with NGEU. However, the NGEU plan was designed to overcome a different type of crisis (COVID-19), with some of the funds already distributed and allocated, so it may not be enough. Further progress must be made in designing a common fiscal response if the NGEU and REPowerEU agendas are to be achieved.