Fed and ECB, at different stages of the normalisation process

In a context of unusually high inflation, the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank have stepped up and are in the midst of the monetary policy normalisation process, albeit at different rates.

Inflation in the major advanced economies is at unusually high levels. This has been driven, among other factors, by the rise in energy prices and the bottlenecks resulting from the limitations of supply in meeting the rapid recovery in the demand for goods. In this context, the central banks have stepped up and are in the midst of the monetary policy normalisation process, albeit at different rates. In March, the US Federal Reserve raised interest rates by 0.25 pps, announcing that it expects to engage in a much more aggressive cycle of rate hikes than that seen between 2015 and 2018, and suggesting that it could begin to reduce the size of its balance sheet between May and June. In contrast, the ECB merely anticipated that it would increase the size of its balance sheet more gradually and possibly keep it constant from Q3 onwards, a decision that must precede any future interest rate hikes.

The differences between the Fed and the ECB

There are various factors that explain why these two central banks are at different stages in the normalisation process. The first is the difference in the origin of the inflationary pressures. While the high inflation in the US and the euro area share some common causes, such as rising energy prices, in the US core inflation is much higher (6.4% compared to 3.0% in the euro area). A key factor behind this higher core inflation in the US is the greater impact of the bottlenecks, as a consequence of the country’s broader and more generous direct fiscal aid compared to the euro area. Also, the labour market, key in explaining the medium-term inflationary pressures, is under much greater strain in the US than in the euro area. While the unemployment rate in both regions is below the pre-pandemic level, in the US some indicators suggest much higher tensions (for instance, wage increases in the US are exceeding 5%, while in the euro area they are below 2%).1

The second factor that explains the Fed’s more aggressive response compared to that of the ECB is the lower impact of the war in Ukraine on the US economy. Given its distance and its lower energy dependence on Russia,2 the US economy is more isolated from the impact of the war than the euro area, though its effects will also be felt both through the higher energy prices and through lower confidence among households and businesses.

It is clear that the ECB and the Fed are in different situations. The ECB is concerned about inflationary pressures but convinced that it is still on time to prevent inflation from rising above its target rate in the medium term. The Fed, which is surely running late, is concerned with tackling a price dynamic that is far in excess of its targets.

ECB: avoiding a spike in inflation expectations

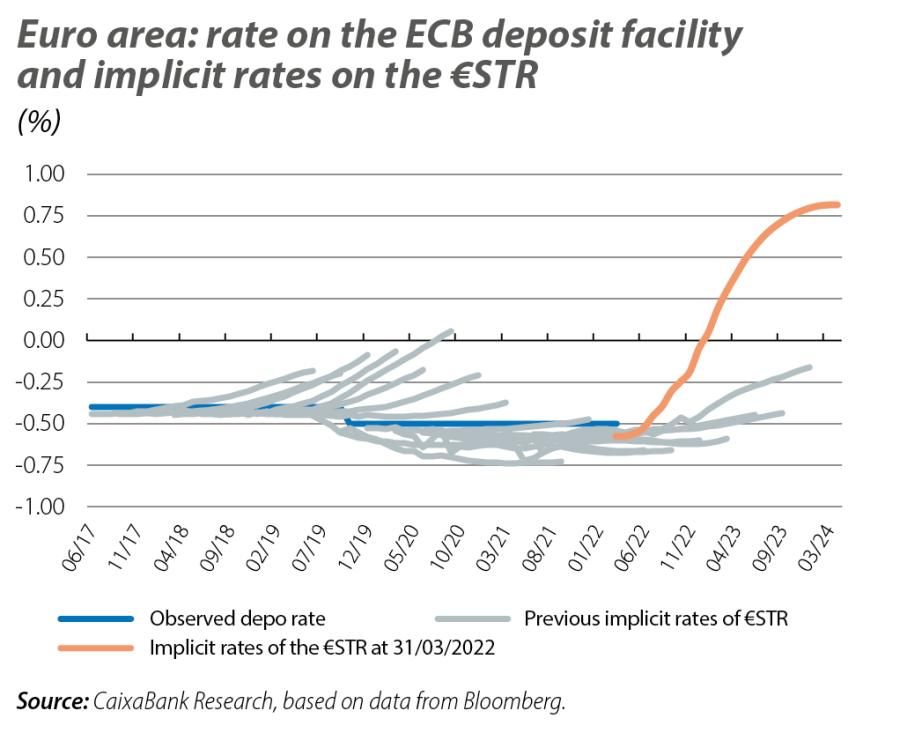

Given its inflation target, the ECB is withdrawing the monetary stimulus much more gradually than its counterparts in other advanced economies, but it nonetheless seems determined to normalise its monetary policy. For instance, in terms of asset purchases, the ECB acquired a total of 1.11 and 1.09 trillion euros in 2020 and 2021 under the APP and the PEPP, respectively, while in 2022 this figure could be reduced to 0.27 trillion. Also, the likelihood that the ECB will make its first rate hike since 2011 in the next 12 months is very high.

The main objective of this normalisation is to prevent the medium-term inflation expectations from deviating from the 2% inflation target, in this case with an upward shift. While long-term inflation expectations in recent years have been pointing to levels well below 2%, in recent months they have risen to around the target. A first rally occurred last summer when the ECB adjusted its strategy and implied that it would be somewhat more permissive on inflation. And in recent weeks, there has been another rally triggered by the conflict in Ukraine, which, beyond the short-term impact on energy prices, is expected to contribute to rising core inflation in the medium term.

Still, the war in Ukraine is a shock that is generating a great deal of uncertainty in relation to the economy, as well as in relation to the response from the ECB. While the conflict is fuelling inflationary pressures, especially in the short term, it could also weaken economic activity and adversely affect inflation in the medium term. In this uncertain context, the ECB is likely to decide to exercise caution and, even if it stops net asset purchases under the APP in the second half of the year, it will not necessarily introduce the first rate hike as early as the financial markets are currently suggesting.

Fed: balancing the need to cool the economy without triggering a recession

The Fed, on the other hand, is expected to pursue a rate hike cycle amounting to at least 1.75 pps over the course of this year and bringing interest rates into restrictive territory in 2023 and 2024 (above 2.4%, the level which the median voter on the FOMC considers to be the long-term equilibrium rate). In doing so, it is seeking to restore price stability without necessarily dragging the US economy into a recession. Finding the balance to avoid a recession will be a daunting task for FOMC members.

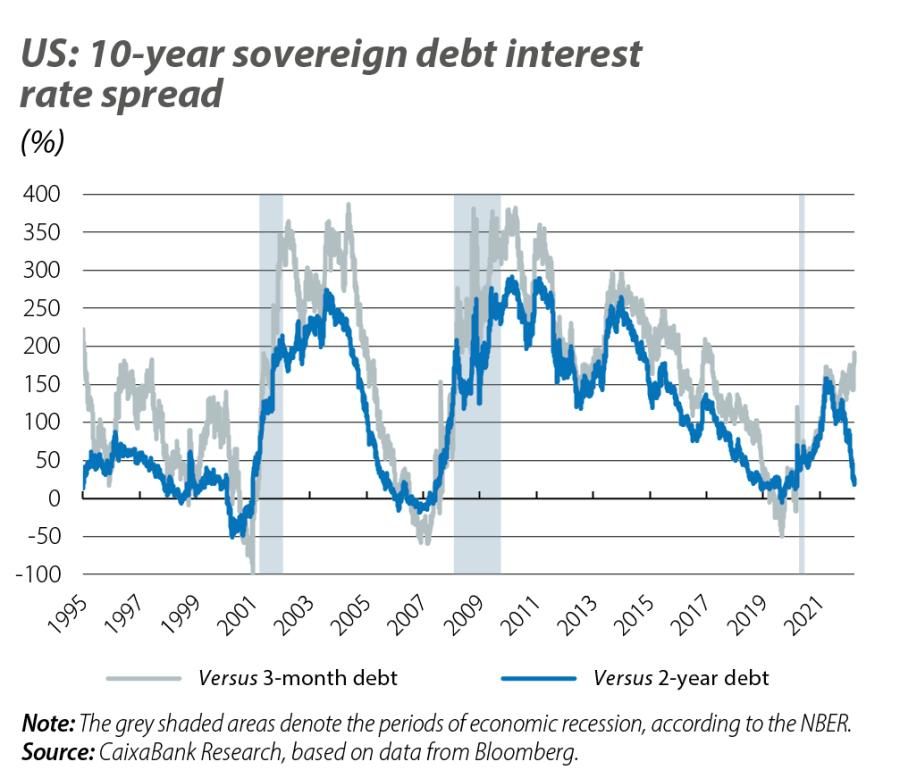

To assess the probability that the financial markets attach to a recession in the coming years, we usually look at the spread between the interest rate on 10-year sovereign debt and on other shorter maturities. Normally best spread to predict recessions in the next 12 months is that between 3-month debt and 10-year debt, and this is not currently showing any indications of a looming recession.3 However, the spread between 2- and 10-year debt is already very narrow (and has even momentarily inverted). This suggests that the financial markets may now be assigning a higher probability to a recession occurring in the coming years, driven, for instance, by an aggressive tightening of monetary policy by the Fed. So, despite Jerome Powell’s firm decision to raise interest rates – even with some 0.50-pp rate hikes – we believe that the Fed will not be able to ignore these indicators and will have to tread carefully, especially if inflation moderates towards levels closer to 2% in early 2023 as we expect. What is clear, however, is that in an environment of high geopolitical uncertainty, commodity price volatility and production bottlenecks, the central banks will need to have plenty of flexibility in order to respond to ever-changing needs.

- 3The rate on 3-month debt is closely tied to the official Fed rate, and that rate is still very close to 0%, while the 10-year rate is around 2.5%. For further details, see «On the likelihood of a recession in the US» in the MR05/2018.